Part of my day job is breaking down unfamiliar concepts–amortization, electric utilities’ Integrated Resource Plans, gas cost recovery mechanism, etc.–into digestible definitions and examples that are understandable to someone who doesn’t know ROI from the IRA. It’s a necessary part of the bureaucracy–lawyers have a bad habit of assuming everyone is on the same page, when most people get turned off by the cover. Introducing entirely new concepts to people is a combination of diplomacy, therapy, and linguistics, and the messenger has to be careful to neither overtask nor condescend to their audience.

Magic, like most games, has the benefit of being experienced–in aggregate–with low stakes and assumed congeniality. We’re playing a game because we want to have fun with our friends, not trying to puzzle our way through a business license application or avoid inadvertent tax fraud. Rules are crucial to a game’s function and are carefully calibrated by their designers to be understandable, predictable, and egalitarian, but if you miss out on a rule or two, you may just have a slightly less balanced experience, and not go to federal prison for a decade. Some stakes are higher, though, whether it’s a tight match to get you into the money at a major tournament or a tabletop wargame that teaches you the tactics you need to know to get the drop on a Hungarian regiment.

The history of tabletop wargames begins with chess, but, as I’ve said, my job is condensing information, so we’ll skip ahead to the 19th century. In Prussia, a junior officer named Georg Heinrich Rudolf Johann von Reisswitz adapted his father’s prototype wargame into a portable and marketable version that he called Kriegsspiel, which saw eventual adoption as a training tool for field officers. His game was extremely complicated, required an expert adjudicator to oversee the game, and was based on hyperlocal terrain.

Notably, though, it included ludic components that we still have today: armies received persistent damage in a proto-hit-points system and the adjudicator was effectively a DM/GM who rolled all dice, relayed all outcomes, and served as arbiter during rules disputes. And, much as we see in modern tabletop gaming, there were rules disputes to go around. By the 1870’s, there were competing schools of thought and written treatises about how the game should be played and how rigid the rules system should be, sparking volleys of communique between Kriegsspiel players that are thematically indistinguishable from modern forum battles. Kriegsspiel is still played in some circles, but it has a high barrier of entry and a commitment to verisimilitude that turns some people off. Still, it proved the model had an appeal not just as a way to pass the time, but as a way to teach skills.

Modern war meant modern wargames, with a post-WWII economic boom and cultural familiarity with war through media exposure leading to a glut of realistic war tabletop simulators, beginning with 1953’s Tactics. I have some of my father’s wargames from this period, and it’s grim stuff–analogous to our modern wargames in the same way that a slide rule is to an iPhone. That said, the generation of gamers trained on these early modern wargames created their own and gave us the second generation of Axis and Allies, The First World War, and Dungeons & Dragons. D&D’s major innovation was tying player investment into its actual concept–when you’re creating your own character, rather than playing as an unnamed commander marshaling faceless forces, every twist of the campaign has an emotional impact. It’s hard to develop an emotional connection to a cube representing a 100-soldier platoon, but very easy to develop one when it’s a barbarian you named and played through to Level 12.

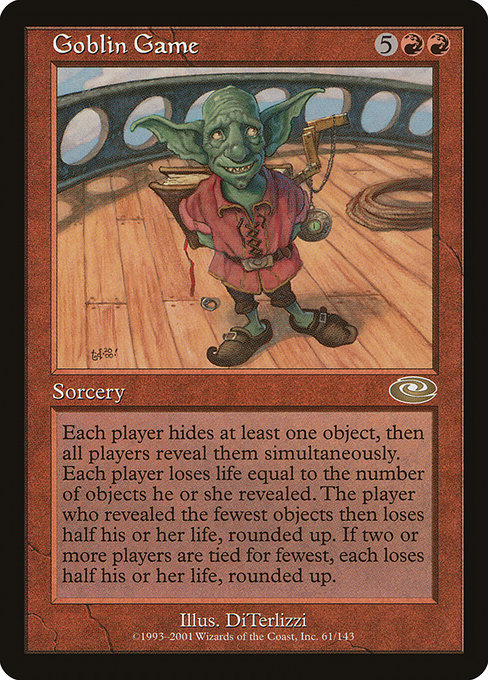

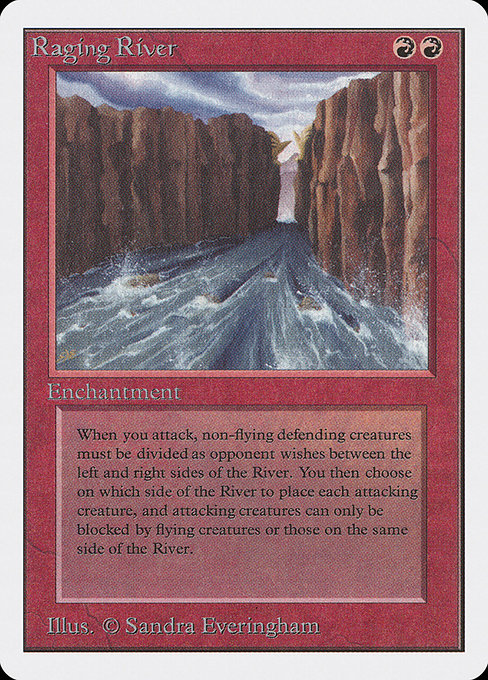

There were precursors to Dungeons & Dragons that welded fantasy onto the grognardian arcana of realistic wargames, but it was Dungeons & Dragons that hit the target. Magic: the Gathering was designed by and for Dungeons & Dragons players, people who had a set of schema about fantasy tactics and who would automatically grease the clunkier parts of the game with their affinity for spellcraft and strategy. Fireball is opaque to your average American in 1993 but, for someone who is familiar with the wargame/videogame concepts of hitpoints, splash damage, and spellcasting, it slots into a comfortable compartment in the brain. We didn’t cast Raging River because it made sense, but because it felt cool (and, importantly, for the sorts of nerds who would go on to debate club and law school, the ambiguousness of the card was part of the appeal). And Magic wanted us to feel that sense of potential in its earliest days, down to seeding cards with pathways towards next-level thinking. It’s a hard enough battle to get your players to understand the rules, let alone to understand strategy. So early Magic–very early Magic, that is–had to have an almost conversational dialogue between the players and the game pieces.

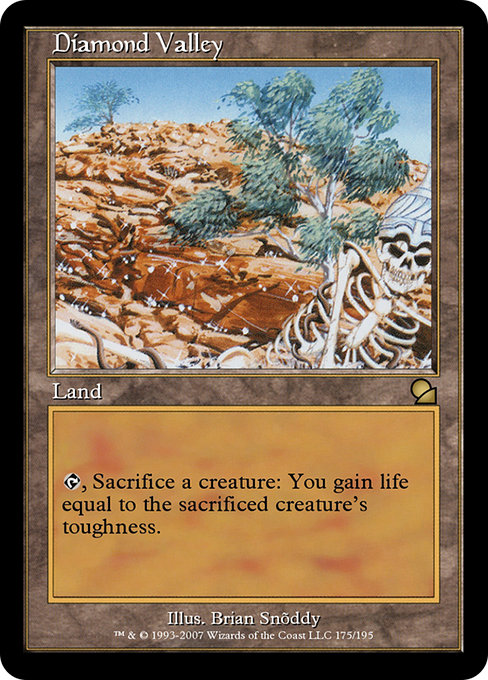

Take Arabian Nights’ Diamond Valley, whose original text reads “Tap to sacrifice one of your creatures in exchange for a number of life points equal to its toughness. Note that this ability may be used after blocking has been declared.” The base level interaction of Diamond Valley is “play a creature, sacrifice the creature immediately to gain X life.” The next level is “play a creature, hold it back to block, then sacrifice it when it’s absorbed a certain amount of damage,” thus essentially gaining you X+Y life, where Y is the amount of damage you’d have otherwise taken from the unblocked creature. For experienced Magic players, that’s second nature, but in 1993, having the card suggest it to you unlocked a new level of understanding the game’s intricacies.

Its current Oracle text is “(tap), sacrifice a creature: You gain life equal to the sacrificed creature’s toughness.” Unlike many cards from the era, the Oracle wording doesn’t change the function of the card at all, merely updates the language to reflect modern game terms. Yet removing that helpful tip has changed the card’s presentation, from something that wants you to play optimally to a card that’s carefully guarded and neutral. Imagine if Orcish Bowmasters read “Whenever an opponent draws a card except the first one they draw each turn, including as a result of cards like Brainstorm, Orcish Bowmasters deals 1 damage to that player.” Diamond Valley is closer to a video game tutorial–a little popup message during combat that reminds you “hey, you can do this at any time–including now.”

For another example from the same set, check out Ring of Ma’ruf–while the Oracle text is almost identical to the original printing, the removal of the italics siphons away some of the fun of the card. “Can you believe this?” the italics imply. “From outside of the game!”

I miss this style of discursive rules text, even if it was only in the game for an early moment. We have a hangover in “summoning sickness,” which has long been a quasi-official (and character-saving) way to refer to being unable to attack and use tap abilities on the turn a creature debuts. Wizards may refer to summoning sickness as “informal,” but it’s shown up as shorthand as recently as Dominaria United in the reminder text for Enlist, so I’d call it at least business casual. Less successfully, Wizards of the Coast tried to create flavorful shorthand in Zendikar with Obsidian Fireheart, which featured the italicized ruling “The land continues to burn after Obsidian Fireheart has left the battlefield.” I applaud them for trying, but “summoning sickness” has stood the test of time while “the land continues to burn” has not.

But I see Obsidian Fireheart as the vanguard of a different trend that Wizards has embraced: flavor words that tie into abilities, as on Dragon Turtle and Redemptor Dreadnought. It helps facilitate understanding of the game for players less familiar with the tropes of Magic–why does Aberrant destroy an artifact or enchantment upon contact? It smashes it with a hammer. These flavor words provide a way for newer players to grasp the semiotics of Magic without directly providing strategic tips, as in Diamond Valley. Universes Beyond cards are aimed at crossover players–people who have an affinity for another piece of culture but maybe not Magic–and so the ability words are a gentle way to smooth the often-opaque experience of learning Magic.

On Twitter and Reddit (and presumably Threads and BlueSky, but after a decade of my brain being warped by Twitter neologisms, I’m not going to stick my hand in that particularly Skinner box again), you periodically see a thread of “what rule did you get wrong when you first learned to play Magic?” The answers are broad: we thought Llanowar Elves let you fetch a Forest each turn, we thought Planeswalkers could use their abilities multiple times a turn, we thought all creatures died when they did combat damage, etc.

There’s no way to catch every rules misunderstanding, and every player who goes beyond the kitchen table has a story where they got outplayed or ruled against by a judge, but by making the cards friendlier, whether through helpful rules tips or evocative ability words, you can at least ameliorate the negative feelings engendered by those misunderstandings. That’s the brilliance of Magic–where wargames and tabletop RPGs are often brutal in their rigidity, with dozens of hours of work undone by a bad roll, you play Magic against an opponent–the game itself wants to play with you.

Rob Bockman (he/him) is a native of South Carolina who has been playing Magic: the Gathering since Tempest block. A writer of fiction and stage plays, he loves the emergent comedy of Magic and the drama of high-level play. He’s been a Golgari player since before that had a name and is never happier than when he’s able to say “Overgrown Tomb into Thoughtseize,” no matter the format.