[Content Note/Trigger Warning: Discussion of the iconography of white supremacy and the Ku Klux Klan. Some references to Nazis and Nazi sympathizers and to hanging as a method of execution.]

The word “kibosh,” in the sense of “put the kibosh on,” meaning “to reject violently or otherwise vehemently veto,” fits into my favorite category of words: the ones marked “of obscure origin.” Morphologically Yiddish, credibly tied to Arabic, it came to popularity in 1836 when used by Charles Dickens, but has been tracked back to 1834. There are several very appealing potential roots for “kibosh,” with two of relevance to our discussion: from the French “caboche,” an informal term denoting decapitation and the Irish “caidhp bhais,” referring to the black cap or hood worn by a judge when passing down a verdict of death. That Irish origin is suspect at best, and it’s more likely that it comes from the Arabic meaning “to whip or lash, particularly with a whip made from rhinoceros or hippopotamus hide.” Whatever its origins, it’s punitive.

Magic has traditionally been a game themed around Wizards in the Euro-American traditional fantasy, which tends towards the flowing robes and pointed hats derived from Merlin and Gandalf, iconography played with by Aleister Crowley, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Alan Moore, and other metaphysicians of the arts. The pointed hat trope comes from a subset of ancient artifacts—archeologists have found four golden, conical headdresses emblazoned with symbols that date back to the Bronze Age. Obviously, their function is obscured by time—they could have been fertility fetishes or symbols of faith in a sun god or, most likely, a calendar or some combination thereof—but the mysticism and opulence of them inspired the traditional Euro-American concept of the sorcerer in a star-spangled pointed hat.

The pointed hat, though, has always been a bit ridiculous, and can just as easily be Ridcully or Big Hat Logan as Gandalf, and so Wizards more frequently defaulted to depicting Wizards in headdresses and hoods, from Ancestral Recall to Simulacrum. The hood is functional and reads well at card size—it’s a very easy signifier to imply that the subject is mysterious or untrustworthy, from the Dimir to Arcanis the Omnipotent to Jace, the Mind Sculptor. As Magic is partially a static and visual medium, and one that uses comedy sparingly, all things considered, the hood better suits the game’s goals.

Prior to Tales of Middle-Earth, Magic players were more likely to see someone who looks like the wizard in Mind Sludge than Gandalf the Grey. Hoods come with their own baggage, though–while the pointed hat or golden cone signifies a mystic sorcerer, hoods are often the accessory of a criminal or malefactor. (Interestingly, the word “hoodlum” has nothing to do with hoods—while hoods are useful for concealing yourself during a crime, the term refers to a specific gang of criminals in 1860’s San Francisco and then passed into common and de-capitalized parlance.)

Hoods aren’t just used to commit crimes, but to punish them. Spanish Catholics may be familiar with the capirote, a long, conical hood that was used as a public humiliation device during the Spanish Inquisition and is still employed by Catholic penitent sects. You can see a stellar example in Francisco Goya’s A Procession of Flagellants. The capirote is designed to draw focus away from the faceless penitent up heavensward, but it also distorts and dehumanizes the silhouette. It dehumanizes and deidentifies, much as many cults–including Magic’s Cabal–shave their heads to humble and dehumanize themselves. There’s some research that suggests the white hoods that became the cultural symbol of the Ku Klux Klan in 20th century America are based on the Catholic capirote and some that suggests the two, like “hood” and “hoodlum” are unrelated, but, unlike the capirote, the point of the Klan hood is to disguise and invoke terror.

It’s debatable as to whether the Klan actually wore hoods. The Klan was a social organization of businessmen, entrepreneurs, and landowners who moonlit as terrorists; the base of the Klan in many locations was not sharecroppers and backwoods swamp-combers, but the economic aristocracy, judges and factory-owners and major farmers. It was the sort of organization that could spotlight over 1,000 members in propaganda films in the 1920s–Kenneth Jackson’s 1967 book The Ku Klux Klan in the City is one of the better resources for understanding the importance of the Klan to American society in the first half of the twentieth century and a corrective to the nationalist terrorist fraternity as it exists in the public imagination. It was not an organization whose members needed to hide their faces when they came together to terrorize their neighbors: they held all the power, they did not fear reprisal. Indeed, for the subjects of their campaigns of violence, it was more frightening for them to be unmasked: “I don’t fear you,” says an exposed face. “If you make it out of this alive, which is debatable, it doesn’t matter if you can identify me in a lineup.”

That said, the iconography of the Klan as established circa 1920 by The Clansman and Birth of a Nation very much employ the imagery of the Klan hood, which has a resonance with the iconography of wizards in some of the hierarchical ranks of Klan leadership. The Klan as depicted in modern white culture is generally something approaching “sinister buffoons,” as in Django Unchained, Blazing Saddles, and O Brother, Where Art Thou? Spike Lee has a more historically realistic take in BlackKklansman and Michael Bay, of all people, a more satisfying one in Bad Boys 2. The burning cross surrounded by ghostly figures may not have reflected the reality of the Klan post-Reconstruction, the terror campaigns of which were more often family-friendly carnival atmospheres that more resembled public executions of the Middle Ages. The Ku Klux Klan and their sympathizers were reinforcing the common beliefs of the dominant culture, not iconoclastically bucking them, and doing so with the tacit acceptance of their government–why would they mask up? (For a more comprehensive nonfiction look at the symbol of the hood, check out Hood by Alison Kinney; for a fictional but excellent look at the Klan as they operated as a social club, check out the cosmic horror novella Ring Shout by P. Djéli Clark.)

It’s fraught to talk about certain cards, particularly one that plays irresponsibly (and intentionally, judging by the artist’s other work) with tropes of American white supremacy, but a discussion of hoods in Magic is incomplete without touching on the now banned card. Back in 1994, in Legends, Wizards printed Invoke Prejudice, whose art features what could, if you want to be charitable to a fault, an executioner, but more closely resembles, particularly with the context of the card’s name, a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Contrast the hood depicted to the artist’s Nether Void in the same set or to Forgotten Lore, a year later—he knows how to draw more traditional hoods, but elected to employ a very specific type of hood, and to do so very intentionally. The artist, based on their other work, harbors sympathy, if not outright affection, for the Ku Klux Klan and the German Nazi party. His art is unfortunately on several iconic cards in early Magic, but Wizards hasn’t worked with him since Tempest, after which his art became more blatantly bigoted.

Related Article: Wizards Bans 7 Cards with Racist Depictions, Including Invoke Prejudice

The capirote may have not inspired the costume of the American Klan, but it does appear to have inspired another famous penitent/sadist in Silent Hill’s Pyramid Head. The mythos of Silent Hill is pretty opaque and the canon is debatable, but Pyramid Head is often depicted as a combination executioner-penitent who punishes those condemned to Silent Hill, a role he served in his debut in Silent Hill 2. The design of a burly masculine form with its head encased in a rusty, pyramidal cage is iconic, but its designer, Masahiro Ito, has expressed frustration with this specific iteration of Pyramid Head showing up in other media outside of Silent Hill 2, Tweeting to ask why the “White Hunter” version isn’t the standard.

Globally, that’s a valid question, but I do think there’s a reason why American developers and producers haven’t been eager to jump on a video game antagonist who wears a white hood. It’s difficult to even touch on that imagery, which goes hand-in-hand with some of the cruelest acts in American history. A much safer referential palette is to the European executioner, as embodied in Unstable’s Hangman–a beefy, shirtless man with his head covered by a (crucially non-pointed) black sack. This imagery shows up everywhere from old Far Side and Looney Tunes cartoons to Resident Evil 4 to low-rent Halloween costumes–it’s become one of the Euro-American cultural tropes along with the cowboy, the torch singer, the quarterback, etc.

In Magic, it shows up mainly in civilized societies on Ravnica and Fiora and Otaria and especially Innistrad, Dominia’s repository for frightening and grisly tropes. I was mildly surprised to see how much capital punishment is present in the society, which is mainly focused on scrounging up enough firewood and grit to drive off werewolves and vampires–doesn’t seem like there would be much time left to violently enforce social boundaries and commit state-sanctioned murder.

That’s me being an optimist, though–it seems more likely that societies experiencing existential threats are more likely to harshly and fatally punish dissidents from within. So Innistrad has gallows a-plenty and hooded executioners standing by to chop those who escape the clutches of the nocturnal predators, from Gallows at Willow Hill to Undead Executioner and even a double header in Hanged Executioner. It makes sense, as Innistrad is based partially on 15th-18th century Germany–for more on the history of executioners in that milieu, check out Joel F. Harrington’s magisterial The Faithful Executioner.

Dark Ascension gave us Executioner’s Hood, a stellar art on a profoundly mediocre card. Thematically, sure, executioners are scary, but granting Intimidate in a set that was designed to show how feral and paranoid Innistradi society was becoming is a missed opportunity, particularly in a block rife with Equipment that gave Humans other abilities. Notably, the stitching and the Collar of Avacyn in the background mark this specific executioner as a tool of the Church of Avacyn–this is a zealot who moonlights as an executioner, one of the scariest things imaginable.

In contrast, Eldritch Moon’s Extricator of Sin does a very good job of evoking the capirote and the executioner’s hood without falling into suspicious semiotics—the mask/helm the Extricator wears is martially functional, concealing, and intimidating, and looks threatening on both the Human and Eldrazi forms. It suggests an executioner’s hood that’s both functional as a battlefield helm, recognizable as an icon of state-based terror, and alien enough to imply the Eldrazi menace waiting on the other side of the card. It’s one of my favorite stories from Shadows Over Innistrad block–an executioner who, in doing their duty, comes into contact with an Eldrazi and betrays humanity immediately. Their flesh mutates, but the heraldry of their station remains: if you dispassionately carry out the work of killing those the government deems undesirable, don’t be too startled when you realize you’re no longer human.

While executioners work for the government, some hooded killers are happy to freelance. Kev Walker’s art for the Commander Masters reprint of Grave Pact is characteristically stellar, with an emerald-hooded figure looming over a figure with a trowel-bladed anelace, a broad, triangular dagger. Other arts for Grave Pact have been direct to the point of silliness–Puddnhead’s theatrical open grave, Tony Szczudlo’s art right out of A Christmas Carol, Scott Kirschner’s POV of the interred–so it’s nice to have a more ambient piece. Even then, Walker’s art makes the dynamic clear: the hooded figure thinks they’re enacting the sacrifice, but the dramatic irony is that they don’t realize they are the object of the sacrifice. Plunging the dagger into the shrouded figure isn’t the end of the sacrifice, but its beginning: the figures in the background stand ready to close in and finish the ritual with their brother’s blood. The hood isn’t to conceal the dagger-wielder’s identity, but to dehumanize them into an animal, waiting for the slaughter. Often, it’s not just the executioner that wears the hood, but the one awaiting execution.

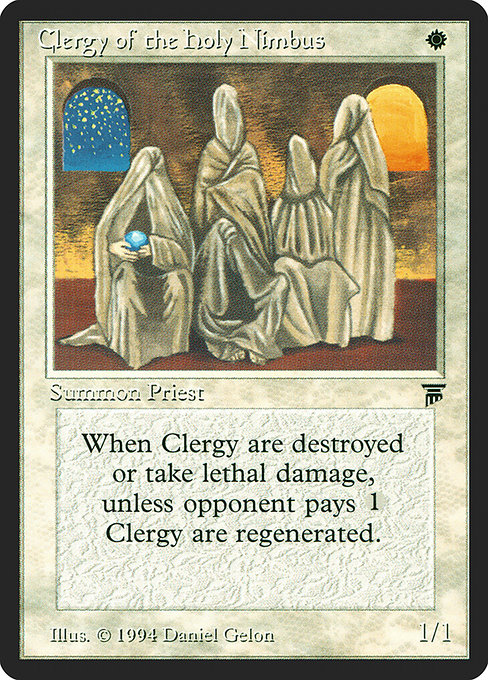

The purpose of a hood, whether a capirote or an executioner’s hood, is to conceal one’s identity, in some cases for noble reasons, in others, for sinister reasons. In the case of Kev Walker’s art, it’s to hide your face during sacrificial rituals. In the case of cards like Keepers of the Faith and Clergy of the Holy Nimbus, it serves the same role as the capirote—to deny your identity in service of a religious cause, to subsume your own self in favor of exalting the faceless ineffable.

The semiotics of a hood are complex–culturally, we think of hoods as shrouding the face of an executioner, but historically, they were more often worn by prisoners, as they restrict vision and make it easier to dehumanize a captive. (See the indelible images out of one of America’s torture camps in Abu Ghraib, where a prisoner stands as if crucified on a box, electrical wires wrapped around his arms, a pointed hood hiding his face.) From the capirote to the dunce cap to the hood of the doomed cultist in Grave Pact, the hood is a way to erase humanity, whether self-applied or other-applied, and a way to seek enlightenment through self-effacement. By becoming faceless, we become an object–either a tool of the state in the case of capital punishment or a member of a unified multipartite body in the case of a cult–and our identity under the mask ceases to exist.

Rob Bockman (he/him) is a native of South Carolina who has been playing Magic: the Gathering since Tempest block. A writer of fiction and stage plays, he loves the emergent comedy of Magic and the drama of high-level play. He’s been a Golgari player since before that had a name and is never happier than when he’s able to say “Overgrown Tomb into Thoughtseize,” no matter the format.