Richard Garfield’s original concept for Magic was interwoven with color identity and was built around the tension between the five philosophies (the game’s original name, while in development, was Mana Clash), meaning games were as much about sabotaging your opponent’s plans as they were about enacting your own. Games were meant to be decided by “Cast my Interrupt, Sleight of Mind, to switch your Circle of Protection: Blue to Green, attack with Mahatmoti Djinn, claim both cards in the ante.”

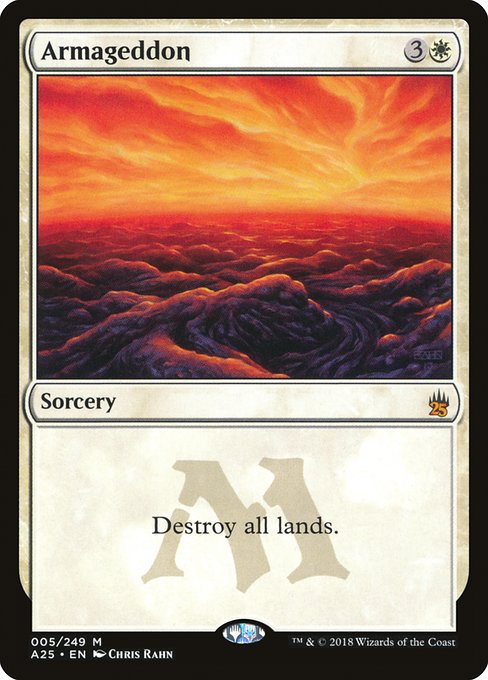

That’s a pretty opaque sentence to anyone who started playing post-Sixth Edition (which has to be something like 96% of Magic’s current audience by this point), but what it Boils down to is that early sets were loaded down with color shifting, land destruction, and truly punishing color hosers like Perish and Stench of Evil. If you didn’t get your lands targeted by Strip Mine, Sinkhole, or Armageddon, you still had to contend with an opponent dropping a Conversion or a Flashfires on you.

Out of the 276 non-land cards printed in Beta (which included the Circle of Protection: Black and Volcanic Island that were missing from Alpha), by my count, 57 directly refer to a color or a land type, from Red Elemental Blast to Circle of Protection: Red to White Ward. Evil Presence, Cyclopean Tomb, Conversion, Magical Hack, Phantasmal Terrain, Flashfires, the list goes on and on—Richard Garfield knew what a good thing he had hit upon with Magic’s mana system, and Alpha/Beta had a rock-solid devotion to making land types and color matter, perhaps to a fault.

This doesn’t even include the land destruction that every color had access to, from Sinkhole to Volcanic Eruption to Ice Storm. It wasn’t all the thematic elegance of White Knight versus Black Knight or the appealingly ambivalent Kormus Bell—there was the cycle of Laces at rare (Thoughtlace, etc.), the clunky and borderline-useless Cyclopean Tomb, the cycle of life gaining artifacts like Crystal Rod. All of this was done better, as many things were, in Invasion, which added in-game reasons to switch colors and land types through cards like Hobble and Phyrexian Reaver, but Alpha planted the “color and lands matter” flag from day one.

Richard Garfield applied for a patent in 1995 for the core mechanics and rules of Magic: the Gathering. Patent #5,662,332 was issued on my eleventh birthday—September 2nd, 1997—and granted Garfield/Wizards of the Coast rights to the phases, rules, and card layouts, among other guarantees. In Dr. Garfield’s application, he outlines the basic rules, noting that core gameplay includes “entering one or more energy elements into play and entering one or more command elements into play as the level of energy elements permits to enable a player to attack other energy elements, command elements, and other players, to defend against such attack, and to modify the effect of energy elements, command elements, and the rules of play and alter the state of a player.”

Those “energy elements” are how Garfield initially introduced the concept of lands and mana to his legal audience and they’re brought up multiple times in the sense of altering or destroying lands or shifting colors. It’s an anodyne way to refer to the warring philosophies of the five colors and the frustration of someone cutting your entire deck out from under you, whether with Balance or Boil, but such is the lingua franca of the legal application. In gameplay terms, to “modify the effect of energy elements” mostly meant “hose the everliving hell out of your opponent’s deck if they were foolish enough to run a single color.” Since Magic also punished multicolored decks initially, this led to quirky situations like tournament-winning decks running the Swords-proof Ihsan’s Shade and Serrated Arrows as tech against Order of Leitbur.

There were two models of color hosers in Magic’s early days: the brutal Flashfires/Chill/Nature’s Ruin lockout cards and the less-successful “reward you for your opponent’s color choices rather than punish them” like Compost, Yawgmoth’s Edict, and Insight. Wizards bounced back and forth between these modes from for years, with experimentations into upkeep costs (Mangara’s Equity, Mind Harness, Elephant Grass) and punisher-style choice cards (Reclamation and Sirocco). Wizards also experimented with spells that were free if you were matched up against an enemy color in this time frame, with the Mercadian Masques Legate cycle not seeing much play and the winners from the Nemesis cycle of Submerge and Massacre more than making up for it.

Thanks to the reprint scheme established by the base set model, we ended up with a round of some of these early hosers in Modern through reprints of Boil, Choke, Flashfires, Hibernation, Karma, Sanctimony, Spreading Algae, and Wrath of Marit Lage (Black got Slay and Execute—reasonable cards, but not the haymaker hosers that the other colors got). Aside from the uncommon hosers, 8th Edition also gave us The Dark’s representative in the “never reprinted” pantheon: Blood Moon. Hoser extraordinaire Blood Moon has been the subject of novella-length articles, so I won’t dwell on it, but I believe it to be a crucial check on Modern—definitely a bit too efficient for what it does, but it punishes greedy manabases and is less frightening in a post-Boseiju world.

9th Edition elected to go a different direction with its hosers. Instead of Spreading Algae, we got Anaconda. In lieu of Wrath of Marit Lage, they gave us Withering Gaze. While all these cards technically fit within the “Modern” cardset, they’re anachronistic in terms of small-m modern design. 10th Edition, however, reprinted the precedent-setting Coldsnap cycle of 1-for-1 efficient reactive hosers: Luminesce, Deathmark, Flashfreeze, and Cryoclasm. Karplusan Yeti was also in attendance. It was shortly thereafter, with the entrance of a new card design philosophy, that we solidified the color hosing practices we’d see for the next fifteen years.

While “Modern” as a format tracks back to the introduction of the modern card frame in 2003’s 8th Edition, I think of modern Magic design as anything post-Alara, as that’s right about Magic’s midpoint (15 years of Magic pre-Alara and 15 years post-). Magic’s major post-2008 design philosophies can be loosely grouped into three eras: the Great Recession era (2008-2012), the post-Modern era (2012-2017), and the Arena era (2018-ongoing). There’s some overlap in those categories, but it’s close enough for our purposes. Note as well the development time inherent in Magic makes talking about design trends temporally tricky—the cards printed in Alara block were being designed about a year earlier, for example.

Critical trends for each era: Alara–Return to Ravnica was about upping excitement for players and attracting new players by streamlining rules and smoothing “feel bad” experiences, the post-Modern era was a reprint-focused and format-tweaking period during which Wizards explored mass reprint sets, and the Arena/Booster Fun era is driven by gameplay flexibility and F.I.R.E. design (a Wizards catchphrase for “exciting, replayable, fun games”—which shouldn’t have needed to be articulated, but there were some rough years there).

The biggest shift from pre-modern to modern design is that we’ve mostly left mass color hosers in the past. Since Alara and the Zendikar boom, we’ve seen hosers change from “lock your opponent out of the game” to “trade one-for-one for cheaper if they’re playing an enemy color” in cards like Noxious Grasp and Celestial Purge and Devout Decree. We no longer get the sort of hyperefficient mass hoser like Boil or even Desolation, nor do we get the sideboard-only also-rans like Withering Gaze. Instead, the model has been, in the post-Modern era, Deathmark—removal that’s a blank against some portion of the field and hyperefficient against enemy colors—and, in the Arena era, Lithomantic Barrage, which is always useful, but becomes more powerful against a deck running Red’s enemies.

The Alara design era was a reaction to the Time Spiral/Lorwyn design mode*, which was self-referential, experimental, and opaque to new players. The watchword at Wizards for this era was attracting new players by designing cards for the “risk averse” neophyte. To do so, Wizards’ design team brainstormed up a new model that included a reinterpretation of Core Sets and an overhaul of Magic’s rules to smooth player experiences (removing mana burn, stack shenanigans, on-board combat tricks, etc.) and making it so that you lost to the cards rather than the rules. This, coupled with the success of 2009’s Duels of the Planeswalkers, meant a huge influx of players—the Shards/Zendikar era player acquisition and retention push was something Wizards could coast off of years, particularly when they hit homers like Innistrad and easy triples like Return to Ravnica and Khans of Tarkir.

Next week, we’ll cover what happens after the economy crashes, the M10 model succeeds, and Magic starts stalling out due to its own success.

*This was my favorite era in Magic history. The sugar rush of Ravnica receded, and Magic hit a mid-life crisis that, like all mid-life crises, was narratively compelling and hilarious to experience from the sidelines. Drafts were grueling/exhilarating exercises in analyzing complicated board states and memorizing all possible options and Standard was completely infested by Faeries and warped by seamless mana. Longtime players were rewarded for their knowledge of the game’s history and familiarity with its more arcane rules, and new players were punished for not getting on board back in 1995. They released Coldsnap and lied in its marketing about its provenance, they released an entire block of Magic: the Self-Referencing, and they dropped an entire block based on Anglo-Celtic folklore with the most off-putting creature designs since Julie Baroh quit painting for Wizards. As a Magic obsessive, it was glorious, but something had to break, or else Magic would asphyxiate from how insular it was becoming. Ravnica was a wide-open door, welcoming new players into a brightly-lit gathering hall with edgy promos on [adultswim] and the promise that you could play anything you wanted, and then immediately afterwards, they dimmed the lights, barred the doors, invited their weirdest friends, and told us we could play anything, so long as it was at Instant speed and could stand up to a Thoughtseize. If there’s one card to embody this era, it’s the textless Player Rewards version of tournament staple Cryptic Command.

Rob Bockman (he/him) is a native of South Carolina who has been playing Magic: the Gathering since Tempest block. A writer of fiction and stage plays, he loves the emergent comedy of Magic and the drama of high-level play. He’s been a Golgari player since before that had a name and is never happier than when he’s able to say “Overgrown Tomb into Thoughtseize,” no matter the format.