The Brothers’ War contains 63 “retro artifact” cards that present powerful Magic: The Gathering artifacts in the old (pre-8th Edition) card frame. Each retro artifact also has a “schematic artifact” version in which the illustration appears as a design drawing for the artifact. In making the schematic artifact illustrations, two artists, Chris Rahn and Titus Lunter, did not settle for making their “paper” or “parchment” background appear old. Instead, they used actual, centuries-old paper. [Disclaimer: Titus Lunter’s original art agent is Donny Caltrider, a friend, Hipsters of the Coast writer, and my writing partner on our collaboration.]

The general consensus among the MTG illustration art community was that this use of antique paper was somewhere between “really cool” and “awesome.” Curiously, my gut reaction was the exact opposite. There was plenty of perfectly good new paper and illustration board in the world. Why drag an antique into the project and alter it irrevocably, just for an illustration?

While I changed my mind after thinking about it some more, the reasons for my initial reaction and the steps that led me away from it got me thinking about antiques, how people use them, and one deceptively difficult question: when does an object become too valuable to use?

Works on (Old) Paper

Before meditating upon the many meanings of “valuable,” let’s look at the two illustrations in question.

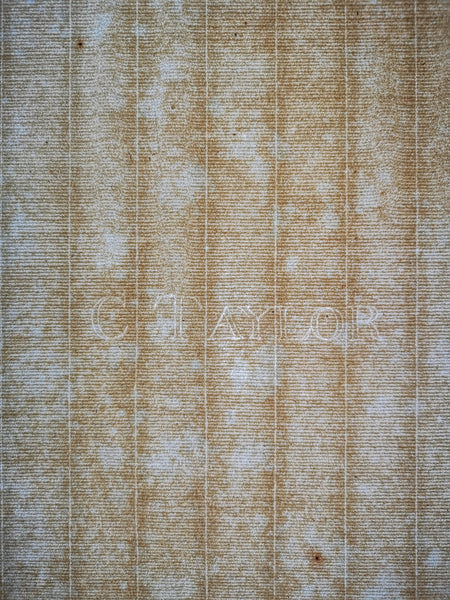

Chris Rahn, taking a suggestion from his better half and fellow Magic: The Gathering artist Alix Branwyn, used English paper from the late 1700s for his Lodestone Golem schematic illustration, according to a post on the private MtG Art Market Facebook group. This paper, until recently available from the Vintage Paper Co, is watermarked “C TAYLOR” for the Taylor family’s paper-making firm.

18th-century C TAYLOR paper, backlit to show watermark, from the Vintage Paper Co.

Rahn paired this with ink applied by a 19th-century-style dip pen to complete the effect. He used two pieces of paper, one for a materials test to make sure the idea would work and the other for the final illustration.

Chris Rahn posing with his Lodestone Golem illustration, from Mark Aronowitz’s auction post.

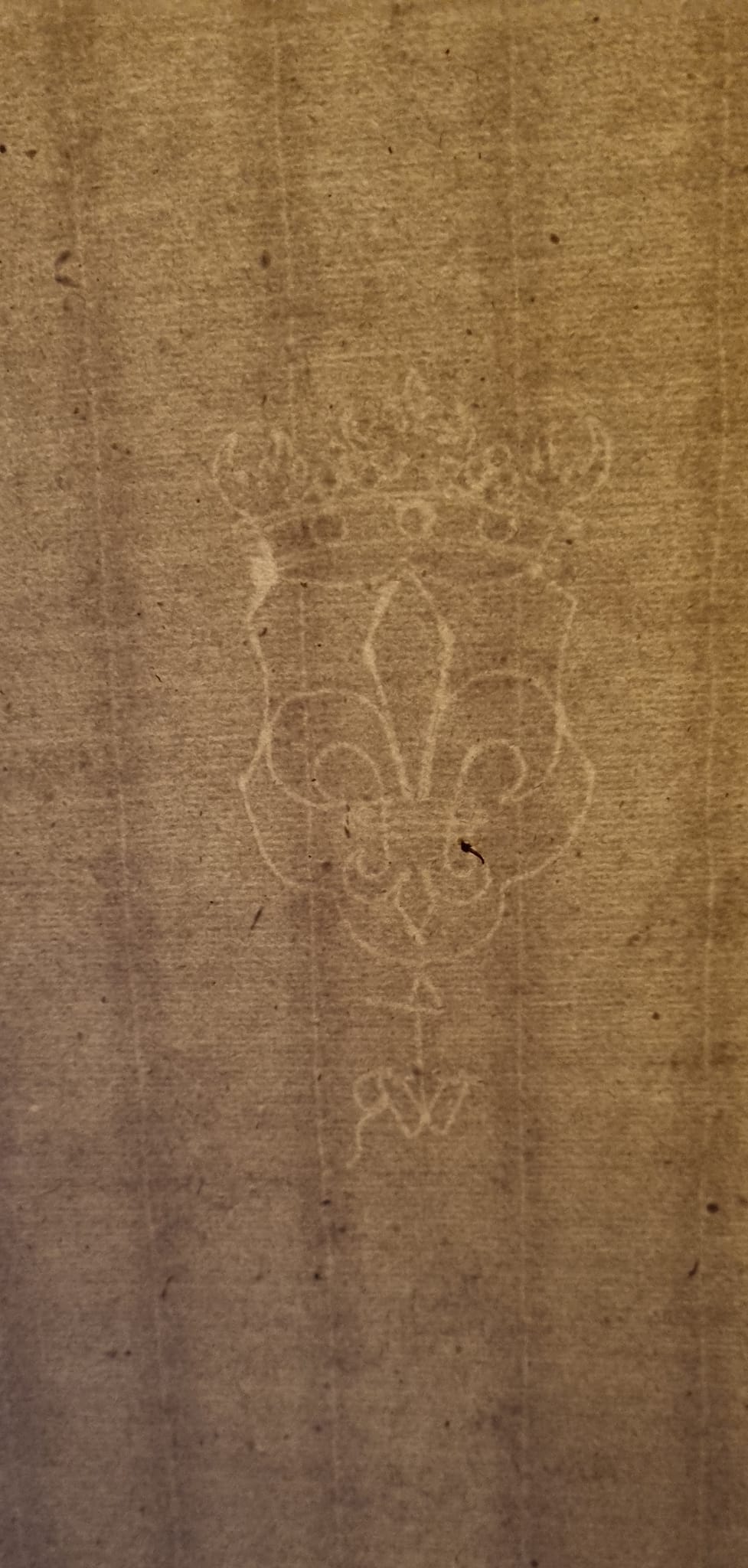

Similarly but independently, Titus Lunter also used antique paper for his schematic illustration of Mystic Forge. Lunter used paper from the 1600s by Wendelin Reihel (also variously spelled Rihel, etc.), one of the most famous paper-makers of its time; Rembrandt was among the artists for whom “works on paper” meant works on Wendelin Reihel paper.

17th-century Wendelin Reihel paper, backlit to show watermark, from Donny Caltrider’s auction post.

Lunter paired this antique paper with ink from Scribo, a relatively new Italian firm whose products closely replicate how ink from the 1700s would write and draw.

Titus Lunter posing with his Mystic Forge illustration, from Donny Caltrider’s auction post.

What Makes an Object Valuable

CECIL GRAHAM. What is a cynic?

LORD DARLINGTON. A man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.

—Oscar Wilde, Lady Windermere’s Fan

“Valuable” is not merely a question of monetary cost, but also of replaceability, durability, and social norms, among other factors.

Two pop-culture moments from 2022 illustrate the complexity at play here. In May, socialite Kim Kardashian appeared on the Met Gala red carpet wearing the same dress worn by Marilyn Monroe when she sang to John F. Kennedy, “Happy Birthday, Mr. President.” In September, pop star Lizzo played a crystal flute once owned by James Madison in the Library of Congress and then briefly at a concert in Washington, DC.

Lizzo plays President James Madison’s 1813 crystal flute in the flute vault at the Library of Congress, September 26, 2022. Photo by Shawn Miller/Library of Congress. Privacy and publicity rights for individuals depicted may apply.

Kim Kardashian donning the dress did not impress experts, though any actual damage to the dress at the Met Gala red carpet may have been overstated. By contrast, Lizzo’s performance won plaudits, with most exceptions showing far more concern for tearing down Lizzo than the flute’s safety. How did the various aspects of “valuable” affect the reactions to the dress and the flute, and how does the use of antique paper for contemporary illustrations rate on the same axes?

Replaceability and Singularity

In discussing replaceability, we must first dispense with two easy and reductive ideas of replaceability. The first is a too-extreme attitude toward any use creating the risk of loss. Consider the classic suburban case of the good china, put up in the cabinet and saved for special occasions, only it turned out no occasion was special enough—and then it goes to heirs who, never having used it and developed fond memories, find it merely a waste of space. One generation’s “too valuable to use” becomes the next generation’s worthless.

The second is the formula that “object + time = irreplaceable artifact.” Objects can be centuries or even millennia old, but still very much replaceable simply because so many were made and so many survive. While the rarest coins of ancient Greece and Rome can sell for millions, it’s trivial to buy a decent-looking Roman Imperial coin from a reputable dealer for under $50.

Instead, it’s better to think in terms of singularity. There is only one Monroe “Happy Birthday” dress, and only one crystal flute gifted to James Madison (though the Library of Congress has more than a dozen Laurent-made glass or crystal flutes). By contrast, antique paper, even 18th century antique paper, is out there for purchase, for $24 a sheet. Price is not the sole determinant of value, but for finding where supply meets demand, it’s pretty good.

Durability and Resistance to Change

Durability and its companion, resistance to change, are key factors in the calculation of risk with use. Monroe’s “Happy Birthday” dress is made out of 60-year-old soufflé silk gauze, fragile on its own and difficult to repair if damaged, making its red carpet appearance (Kardashian wore a replica dress at the actual Met Gala after the red carpet) inherently risky. By contrast, while one might hear “crystal” and instantly think “fragile,” Madison’s crystal flute is more durable than the dress; sure, there’s the risk of chipping or shattering if dropped, but a trained performer like Lizzo can play it safely without the same risk as simply moving in a decades-old delicate dress.

Here, interestingly, the use of antique paper for an illustration scores worse than both dress and flute. From the first line drawn or painted, the paper is changed irrevocably. Once more, this isn’t the only factor at play, but it deserves consideration.

Social Norms and Traditions

Social norms and traditions also contribute to the perceived acceptability of using an antique for its original purpose. Compared to worn textiles, musical instruments have a much broader tradition of active use for decades or even centuries. Wikipedia’s list of Stradivarius string instruments, dating from the mid-1600s to the mid-1700s, shows the expensive and highly prized objects consistently on loan to elite performers or owned by them outright, such as the Gibson Stradivarius violin of Joshua Bell. Lizzo’s flute performance is in good company.

Using up antiques in the creation of an artwork has precedent in the Western tradition. Some of that precedent shocks the conscience, such as grinding up Egyptian mummies to make the pigment for mummy brown paint, a practice that lasted into the 20th century. In the 21st century, Blake Fall-Conroy, perhaps most famous for his Minimum Wage Machine, made Fossil Crusher, a device for sending fossils older than the dinosaurs to their doom.

And Katie Paterson, whose Future Library has drawn both praise for long-term thinking and criticism for withholding its books from the present (and, as Moze Halperin observed, most of the future), ceremoniously destroyed a range of artifacts to make the dust for her 2022 exhibition Requiem. Next to this, using antique paper as the paper time made it, for its original purpose, seems downright tame.

The Alternative

Paterson’s webpage for Requiem reads, in part:

“And in condensing the birth and life of our planet into an artwork Katie Paterson has had to reckon with destruction of another kind, by her own hand, in crushing to dust the precious objects that were donated to the project by so many museums and collections. She has described it as intensely emotional experience—’It felt entirely wrong, and yet the cornerstone of the artwork is loss, and the small window of time in which we now find ourselves.'”

To which one might reply, as my instincts did: Then maybe don’t do it? On the other hand, what is the alternative? The British Museum is not sending off the Sutton Hoo helmet for destruction. The objects of Requiem, while old, almost certainly were not singular, and likely were in poor condition, not making the display cases of regional or even local museums. What good were they doing, moldering in drawers, going unseen for years or even decades at a time? Requiem at least gave them the chance to be part of something new.

And when I consider the alternative for the antique sheets of paper—stuck in inventory, waiting to fulfill their purpose, perhaps crumbling to dust first—the schematic illustrations look even better. Those centuries-old sheets of paper have become part of a decades-old game, their imperfections reproduced by the thousands and shipped to six continents. Admiring collectors have bought the illustrations made upon them; those stories are only beginning.

The instinct to preserve the past is a worthy safeguard against carelessness and heedlessness. The ability to reflect upon that instinct, and set it aside when necessary, is more worthy still. Rahn and Lunter have set out the good china for us art lovers. Fill your cup and take a sip.

Ed Note. This piece has been modified to add contextual clarity around a real-world event that is cited. Additionally, a lengthy Ed. Note has been removed from the start of the article.