Cover Image: Corrupt by Dave Allsop

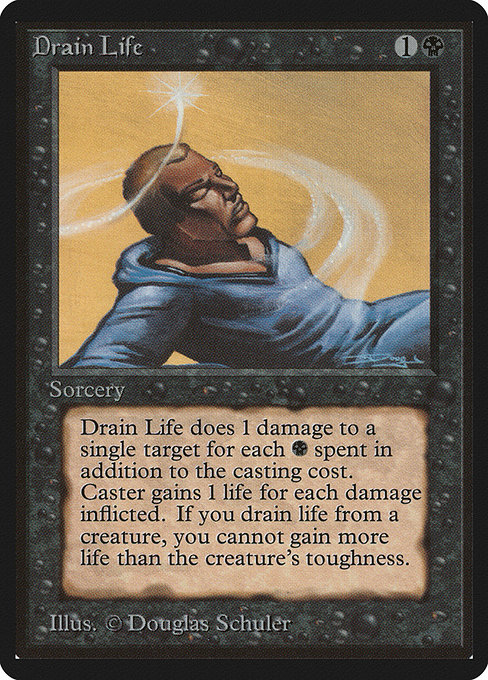

Wizards of the Coast’s pseudo-reprint of Beta has underlined just how much this game got right out of the gate—while Magic: The Gathering’s first set is cluttered with outdated designs like Celestial Prism and Burrowing and Natural Selection, it also brought cards that, thirty years later, still define the game’s philosophy. To Premodern players of today and pre-2000 players of yore, one of Alpha/Beta’s most iconic spells is Drain Life.

Advanced Dungeons and Dragons 2nd Edition (1989) had a notorious spell, Energy Drain, that siphoned levels from monsters or player characters and presumably served as inspiration for Magic’s first designers; Drain Life was a flavorful way to depict a sadistic act of sorcery a la Energy Drain in Magic. It was restricted by a couple of things: one, you had to commit completely to Black mana to drain the target, and two, it couldn’t overdraw the target’s toughness or life.

Drain Life was a secret modal card and, along with Fireball, would start a legacy of design that would eventually lead to Kicker. You could Drain Life late game to take your opponent down to zero or could use it as flexible removal earlier in the game—the only limitation was how much Black mana you could pump into it (and how much life there was to drain).

That dedication to Black mana was instructive; early Magic made the superb design choice to make Black care about your dedication to necromancy and dark magic—cards like Nightmare and Drain Life cemented the commitment to black (or devotion, if you’d rather) that Corrupt, Mind Sludge, and Mutilate later built upon. Every color cared about lands and what they represented, from Flashfires to Karma, but Black specifically powered up the more you saturated yourself in the bogs and bayous, from Demonic Hordes to Lich.

Outside of flavor, Drain Life lucked out as a game piece. Early Magic’s balance was skewed heavily towards Blue and Black and so the spell’s tournament pedigree was strong from the start. It was part of the Necropotence engine during the fabled Necro Summer and it was the win condition for Cadaverous Bloom decks that cashed in cards to make gobs of mana to Drain their opponent out of the game. With Sixth Edition, though, it rotated out of Standard for the first time.

Urza’s Saga, in 1998, brought a kind of replacement in Corrupt, which could do more damage and gain more life at the same price point. Assuming you’re running only Swamps, Corrupt at 5B deals and gains 6, while Drain Life would only deal and gain 4—but Corrupt lacked the flexibility of Drain Life. More than anything, players chose Black back then because it gave them access to Dark Ritual which, hilariously, lasted in Standard until 2002, and could power up Drain Life, but did nothing for Corrupt.

Invasion brought with it a curious reprint: Ice Age’s Soul Burn, which is another iteration of Drain Life, except it costs one more generic mana and allows you to spend Red mana in addition to Black. It’s the same, down to the limitation on the amount of life you can gain and the requirement that any life gain is linked to Black mana spent, not Red. In other words, outside of Red/Black decks, it’s a worse Drain Life, without Drain Life’s nostalgic value—a paltry replacement for an spell that had defined black since the game’s inception.

At the end of Invasion block, Black found itself at a crossroads: it was losing some of the staple cards that made it a powerhouse, and had to establish a new identity amongst sets full of cards that rewarded you for playing more colors, at odds with Black’s traditional role as a greedy color. In earlier years, it had been the color of fast mana, quick creatures with drawbacks, and hand control; as Mercadian Masques and Fifth Edition rotated out, though, they took with them Dark Ritual, Drain Life, and Necropotence.

Black mages were rewarded with Torment and the mono-black control deck that dominated Odyssey block, but Cabal Ritual and even Cabal Coffers weren’t as potent without the payoffs to which Black was used to getting. The reprinting of Corrupt in Seventh Edition confirmed that Wizards was happy with the design and impact of the card, and Drain Life went off to pasture. Standard Mono-Black Control switched to Corrupt—see Osamu Fujita’s Japanese Nationals deck for a representative of what that style of deck looked like—but this big-mana-enabled Standard made the loss of Drain hurt all the more.

Mirrodin brought a streamlined Drain Life in Consume Spirit, which had Drain’s casting cost, flexibility, and black mana requirement, but dropped the annoying limitation of “not more life than the player’s life total before the damage was dealt or the creature’s toughness.” Without Dark Ritual, Necropotence, or Cadaverous Bloom, it fell flat, although it’s definitely an upgrade from Soul Burn.

For a decade, Corrupt and Consume Spirit rotated through Standard, with prints in various Core Sets, but the Ravnica era, and its premier removal that required multiple colors of mana meant mono-black languished. The most successful “Drain Life” variant of all took inspiration (and its name) from Corrupt: Time Spiral’s Tendrils of Corruption. Time Spiral was another format where it was possible—and even desirable—to go mono-colored in Limited, and the Mystical Teachings deck in Block and Standard ran Tendrils of Corruption as tutorable removal that kept you in the game with a shot of life. Unlike Drain Life and Corrupt, though, Tendrils could only target creatures, and thus couldn’t close out a game by itself.

The times Corrupt has shown up in Limited, it’s been surprisingly plausible to pull off a mono—or mostly mono—black deck. Urza’s Saga’s Black had incredible depth—while there were the easy first picks, like Pestilence, Corrupt, Befoul, Dark Hatchling, and Expunge. There were also cards that weren’t in high demand for the non-Black player, like Sanguine Guard, Order of Yawgmoth, and Skittering Skirge. The table’s lucky Black mage could first-pick a Pestilence or Corrupt and then hoover up all of the playable Black removal and creatures to overwhelm their opponents.

By contrast, Shadowmoor’s hybrid mana and Limited opportunity to lock in multiple colors, before pivoting to mono-color, meant that Corrupt was equally attractive for Black-Red or Black-Blue, and could close out the game in conjunction with Elsewhere Flask. Coincidentally, or perhaps by deliberate machination, that same combination is possible right now in The Brothers’ War.

I’ve drafted a mono-Black/artifact deck in the format, and had a blast, but two drafts in a row, I ran with the Corrupt/Flask plan to great success, once in a Blue-Black deck and once in a Green-Black deck (where I was lucky enough to get two Flasks). It’s an unassuming reprint on first glance—temporary mana fixing and a replacement card isn’t much to right home about, but in the context of The Brothers’ War, it does so much more.

The Flask is a cantrip that triggers Gixian Infiltrator, one of Black’s core commons in the set, and can guarantee full power for Corrupt even in a deck that finds itself splashing a second color. Flask tends to wheel—or does so right now, as I don’t expect that to continue in the format for long—and can be run in every deck as an easy-to-cast 23rd card. It triggers “artifact fall” on cards like Perimeter Patrol, Thopter Architect, and Yotian Dissident and can be easy fodder, along with Ichor Wellspring, for Powerstone Fracture. Suddenly, even in a dual-color deck, your life total isn’t safe if it’s the same as your opponent’s land count.

Thirty years on, the rate that Drain Life offers isn’t anything to write home about compared to other removal, but that vaunted flexibility—and its ability to outright end the game by targeting your opponent—means it’s still reflected in modern design. Corrupt has been with us for almost 25 years, and it’s fitting that it returns now as we revisit the Brothers’ War—the flavor has gone from Urza being physically and metaphysically poisoned by proximity to Phyrexia to Mishra being more politically (and eventually physically) corrupted by Phyrexia’s influence.

The tragedy of the brothers lie in their similarities—both brilliant artificers, and both equally susceptible to having that brilliance warped by their short-sighted greed and the corruption of Phyrexia. Flavorwise, sapping your opponent’s strength by serving a dark god and his pestilential minions is grim, but tapping 5B and turning the tables on an opponent who thought they had stabilized at six life is one of the finest—and longest-lasting—ways Magic gives us to win.

Rob Bockman (he/him) is a native of South Carolina who has been playing Magic since Tempest block. A writer of fiction and stage plays, he loves the emergent comedy of Magic and the drama of high-level play. He’s been a Golgari player since before that had a name and is never happier than when he’s able to say “Overgrown Tomb into Thoughtseize,” no matter the format.