Look, I don’t have any love or loyalty to Hasbro. What I do have is a journalist’s desire to read the full report, not just CNBC’s first-page summary, and form my own conclusions. A lot of folks this morning latched onto the headline and the news quickly disseminated throughout the community. Hasbro stock had been downgraded not once but twice by Bank of America. The pre-market value of said stock took a tumble.

The community, led by several prominent influencers, was more than happy to throw fuel onto the fire that had been lit. Many prominent accounts on Twitter took a stance similar to “you reap what you sow” keying in on the idea that they had spent years highlighting some of the same issues that the BofA report highlighted.

Magic 30th Anniversary Edition is overpriced. Too many products are being released. Cards are being overprinted.

But when someone says they did a “deep dive” on the Magic: The Gathering trading card game business, well call me curious but I want to see what that means. I’ve been playing Magic for almost 30 years and I’ve been writing about it form a journalist’s point of view for the past decade. While I appreciate CNBC’s pre-market summary, that’s made for investors, and for the dozens of websites that copypasta that kind of thing. It isn’t for journalists. At least not for me.

So I got a hold of the report, and I read it, and I read it a few more times just to be sure, and we’re going to discuss some Bank of America’s claims about why they decided the future outlook for Magic isn’t as rosy as previously thought, so much so that it’s going to drag the rest of Hasbro down with it. Why do they think the game’s future is in danger, what did their “deep dive” entail, and what did it reveal about the business of Magic?

Before I continue with my analysis of the report I want to make a few disclosures. I am not a financial analyst, advisor, fiduciary, or any of the above. I have never had any job doing so in the past. The closest I’ve ever come to doing so was while working as a software engineer for Morgan Stanley, a competitor to Bank of America. I have not worked in that industry for more than six years now. I am not advising you in any fashion to make any economic decision. I am not telling you to buy, sell, hold, or do anything else with Hasbro stock or any other financial instrument.

I am simply someone who writes about Magic: The Gathering and again, is very interested in a “deep dive” on the business of Magic and want to talk about what I found valuable, what I found questionable, and what I found lacking in Bank of America’s report.

Where’s Arena?

I’m going to start with what I think is the most glaring omission from the 16-page report, and the one that makes me raise the most doubts about the “deep dive” that the report is claiming to have made. The word Magic appears 52 times in the report. The word Arena appears zero times. Given the investment that Wizards of the Coast has made into Arena, as evidenced by the development of Arena-specific formats (Explorer and Historic) and upcoming products (Shadows Over Innistrad Remastered and Dominaria Remastered) plus the inclusion of Arena in the overall organized play plans, it’s absolutely shocking to me that anyone could write a comprehensive report on the business of Magic: The Gathering, its impact on Hasbro’s stock, and not bring up Arena a single time.

Granted, Hasbro doesn’t make it that easy to separate the two. In most of their recent quarterly earnings reports, Arena is mentioned only in passing as part of the overall digital gaming revenue (or lack thereof). However, there’s no denying that the digital games revenue is a significant component of Hasbro’s overall performance, and it isn’t related to a lot of the concerns that the author of the BofA report brings up, which almost entirely revolve around a secondary market that doesn’t exist in Arena.

Where’s Amazon?

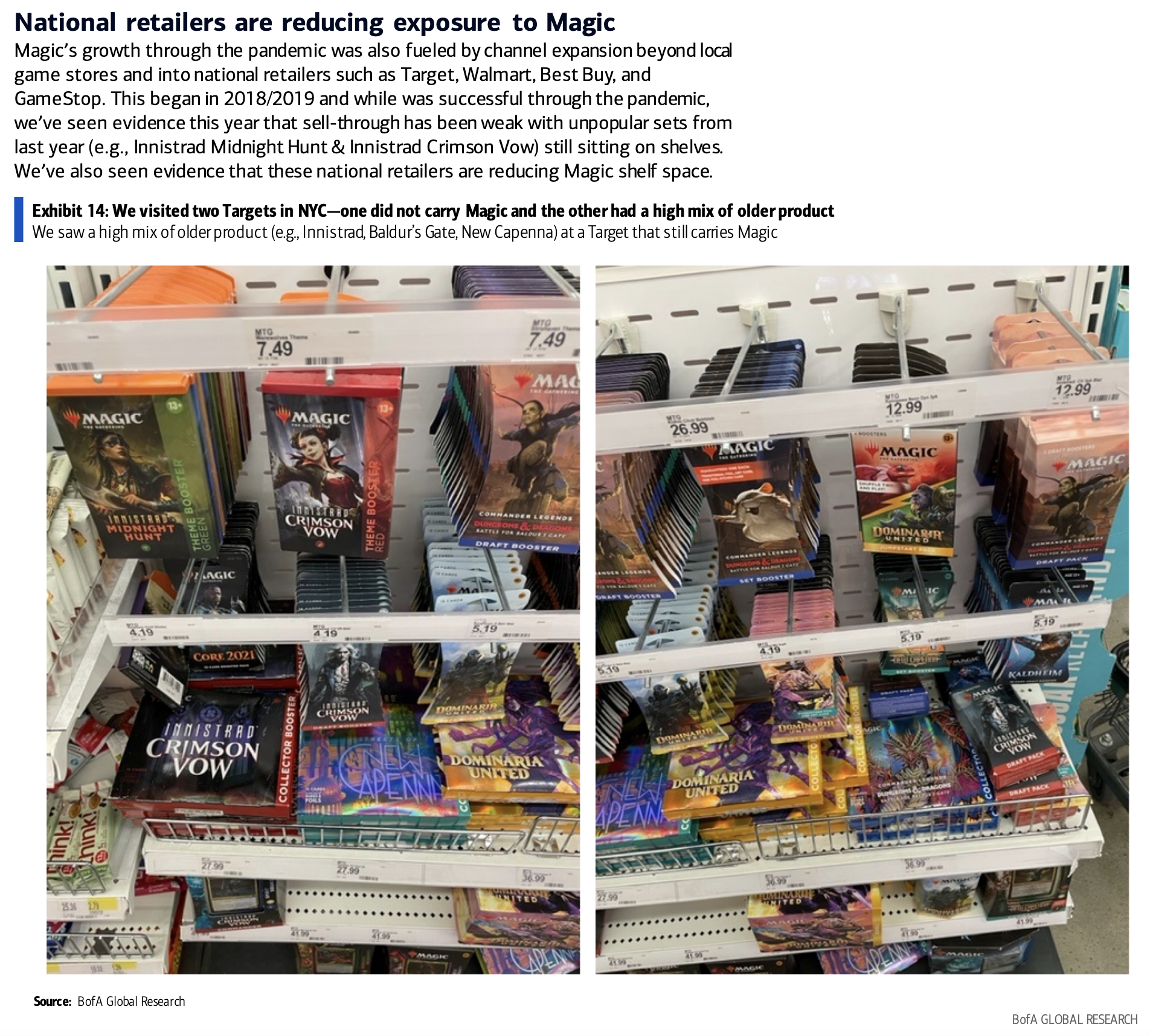

While complaints about product fatigue, overprinted expansions, foil curling, and consumer backlash are all valid community concerns, one of the more significant concerns that the author brings up is retailer inventory. They write, “Our store checks have also found that many national retailers are cutting Magic, and those that continue to carry it are heavy with aged inventory.”

That’s a massive claim, and potentially a huge blow to Wizards of the Coast, who very publicly made the decision to move a large amount of product away from local game stores and into national retailers like Wal-Mart and Target as well as to put product for sale on the web directly on Amazon as well as their own Secret Lair website. So what did the author have to say about this? I’ll let you see for yourself, because I think this page of the report needs to be viewed to be understood.

I might not be reading this correctly, but the claim being made is that national retailers are either a) not carrying Magic at all or b) they are having so much trouble moving Magic product that sets that came out over a year ago are still available, indicative either of overprinting or lack of demand. But then, again if I’m reading this correctly, the evidence to support this claim is that the author visited two Target stores in New York City (of all places).

Conveniently there are two Target stores within walking distance of Bank of America’s corporate headquarters in midtown Manhattan. One of them is what’s called Target Grocery which is not a full retail Target and is very common in New York City where it’s difficult to find space for a full-sized Target. Manhattan is also the home of multiple local game stores, as are the outer-boroughs.

I want to give the author the benefit of the doubt here, but there are some glaring omissions. Was one of the Targets they visited a Target Grocery? Did they try to go to a Wal-Mart? There isn’t any mention of Amazon in this part of the report either, the online distributor who could easily have the same Magic product in my hands within 48 hours without me having to leave my apartment to go to a retailer at all. Amazon is mentioned elsewhere in the report however as a pipeline for Wizards to saturate the market with new product.

As I said above, the Bank of America report raises many valid concerns, but then the extent to which a “deep dive” on Hasbro’s business practices and the business of how Magic: The Gathering is sold leaves a lot of questions to be asked as well.

Focus on the Secondary Market

The author of the report is keenly focused on the secondary market for Magic cards. 10 of the 18 exhibits in the report are sourced from either MTGGoldfish.com or TCGPlayer.com. There is a significant look at the value of the cards on the reserved list, highlighting a downward trend since peaking mid-pandemic as well as a look at the resale value of sealed booster boxes on TCGPlayer.

This focus on the secondary market may be fair, but the author fails, in my opinion, to explain exactly why the secondary market, which Wizards of the Coast and Hasbro have little to no control over, is such a major influence in the revenue growth of the game, as well as the stock price of Hasbro as a company. Here’s the extent of the author’s justification:

And here we get to the crux of the issue. The perspective of an investment banker versus a consumer. Is this a deep dive into the business of Hasbro selling sealed product, the very thing that drives the revenue for the company, or is it a deep dive into the business of investors buying and selling cards and boxes through secondary outlets like TCGPlayer or eBay growing concerned that their cash cow has dried up.

The secondary market has always been a divisive force within the community with many having deeply negative opinions of what is often referred to as “MTG finance.” The never ending deluge of speculative card purchases, malicious entities driving up the price of reserved list cards, and “this product is not for you” reporting has absolutely created community backlash.

The author of the report goes on to argue that Wizards is failing to grow their player base, and instead is relying on increased revenue per consumer, instead of selling to more consumers. Their evidence for this is a Google Trend report which shows that Magic is 15% more popular since 2019 while revenue has increased 65% in that time period. This analysis makes no references to the pandemic spike or inflation nor does it compare that growth to industry competitors.

Where these two claims break down, and where I question the direction this deep dive report has taken, is that the call to cut print runs and inflate secondary market prices for sealed product is directly at odds with the claim that Wizards needs to grow their consumer base. The absolute easiest way for Wizards to grow their consumer base is to make the product cheaper. And Wizards has done exactly that. They have made the entry into the game cheaper, while also creating products that collectors can obtain in the form of Secret Lairs.

What About Box Prices?

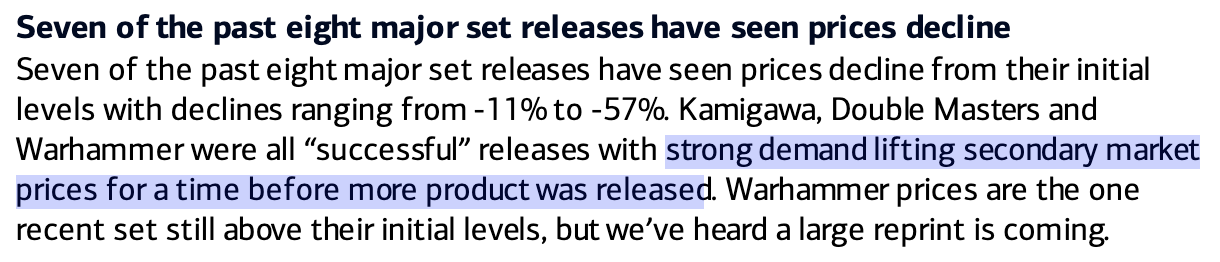

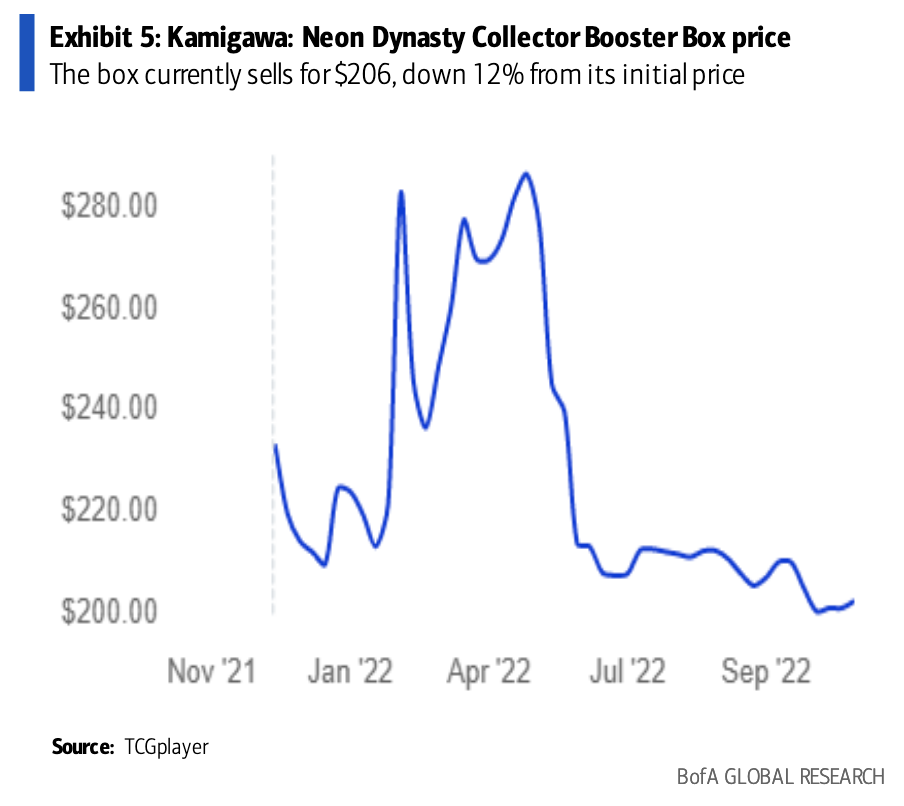

Again, this is a very serious claim being levied by the author of the report. Product prices declining could obviously indicative of lack of demand and could be trouble for both national retailers as well as local game stores who need to decide whether or not to purchase product at all, something that directly affects Hasbro’s revenue. However, the basis for these declines is TCGPlayer pricing that looks something like this:

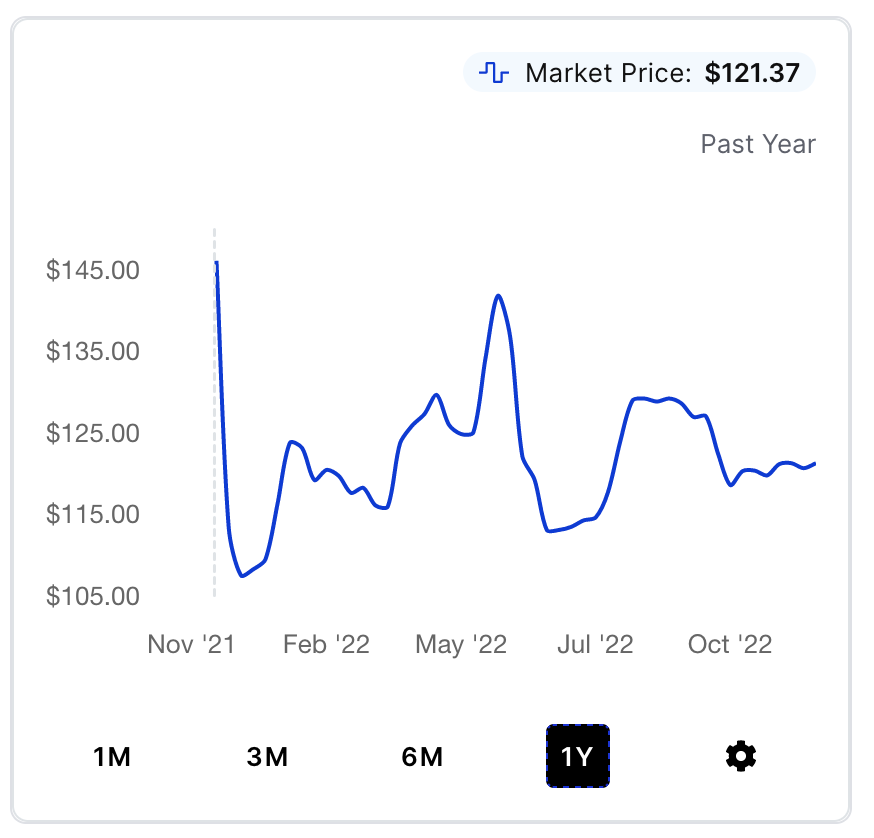

Again, this report is claiming to be a “deep dive” into the business of Magic: The Gathering. However, this graph for Neon Dynasty only includes Collectors Booster boxes. Here, for example, is the one-year outlook for Neon Dynasty set booster boxes:

Source: TCGPlayer.com

It’s important I think to note that Neon Dynasty released in February 2022. The price of a box the week of release was $119. The current price is $121. That’s basically the same but technically an increase, and indicative of the product holding value, not losing value. I’m not going to go through this exercise for every single product that the author mentioned, but again this strongly raises my concerns about the “deep dive” being performed on the business of Magic.

What About Pokemon?

This is one of the last arguments the author makes, but it’s the one that made me cringe the most. The author writes, “While Magic has a dedicated and sticky fanbase, we’re concerned that continued overproduction of cards and declining secondary market values could push players and collectors into other trading card games such as Pokemon, Yu-Gi-Oh!, and Flesh and Blood.”

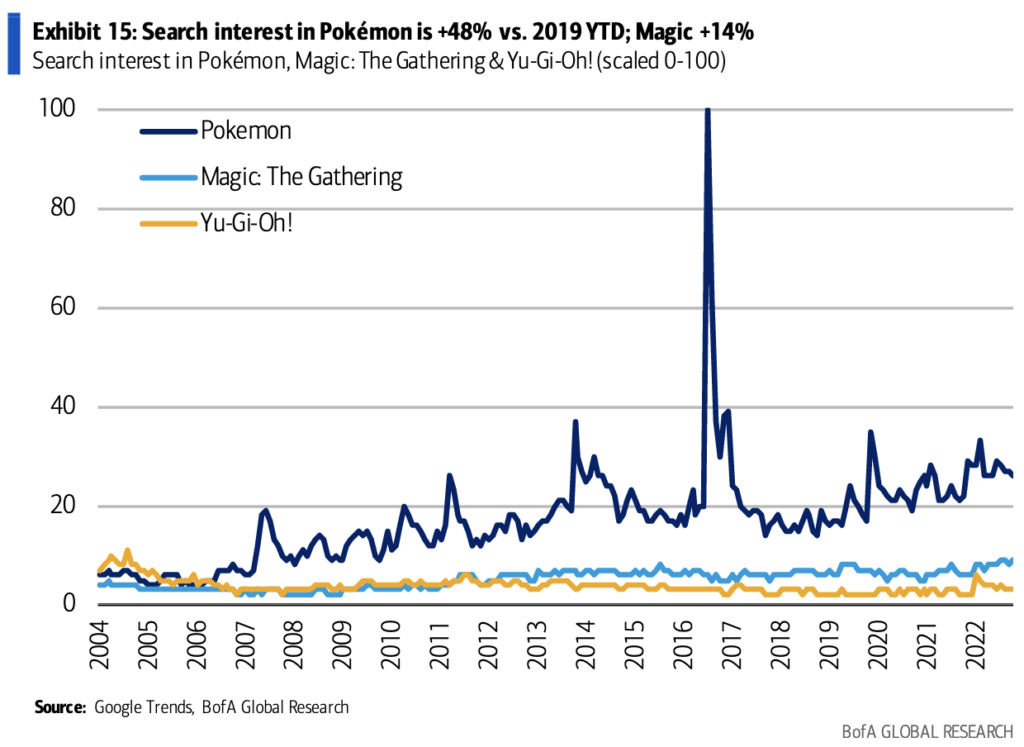

This is then followed by a graph depicting, again using Google Trends, the popularity of Magic compared to Pokemon and Yu-Gi-Oh! over the past 18 years (essentially the entirety of Google trends tracking):

I’ll save you the trouble of looking up what those big spikes in the Pokemon graph are. They’re video game releases for one of the world’s most popular video games, peaking in 2007 (Diamond and Pearl), 2011 (Black and White), 2014 (X & Y), 2016 (Pokemon Go, Sun & Moon), and 2019 (Sword & Shield). If you told me that a “deep dive” into the long-term value of Magic: The Gathering‘s business practices was going to compare a trading card game marketed to teenagers and adults against a video game marketed to children and teenagers I would not have assumed it came from one of the world’s most reputable financial institutions, but here we are.

It should be apparent to any Magic consumer that Pokemon is not a major concern as a competitor either from a long-term collectable perspective or even just from playing the game. Both games have their consumer base and while there is significant overlap between fans of the Pokemon video games and the Magic card games, when it comes to just the card games, there’s not much comparison.

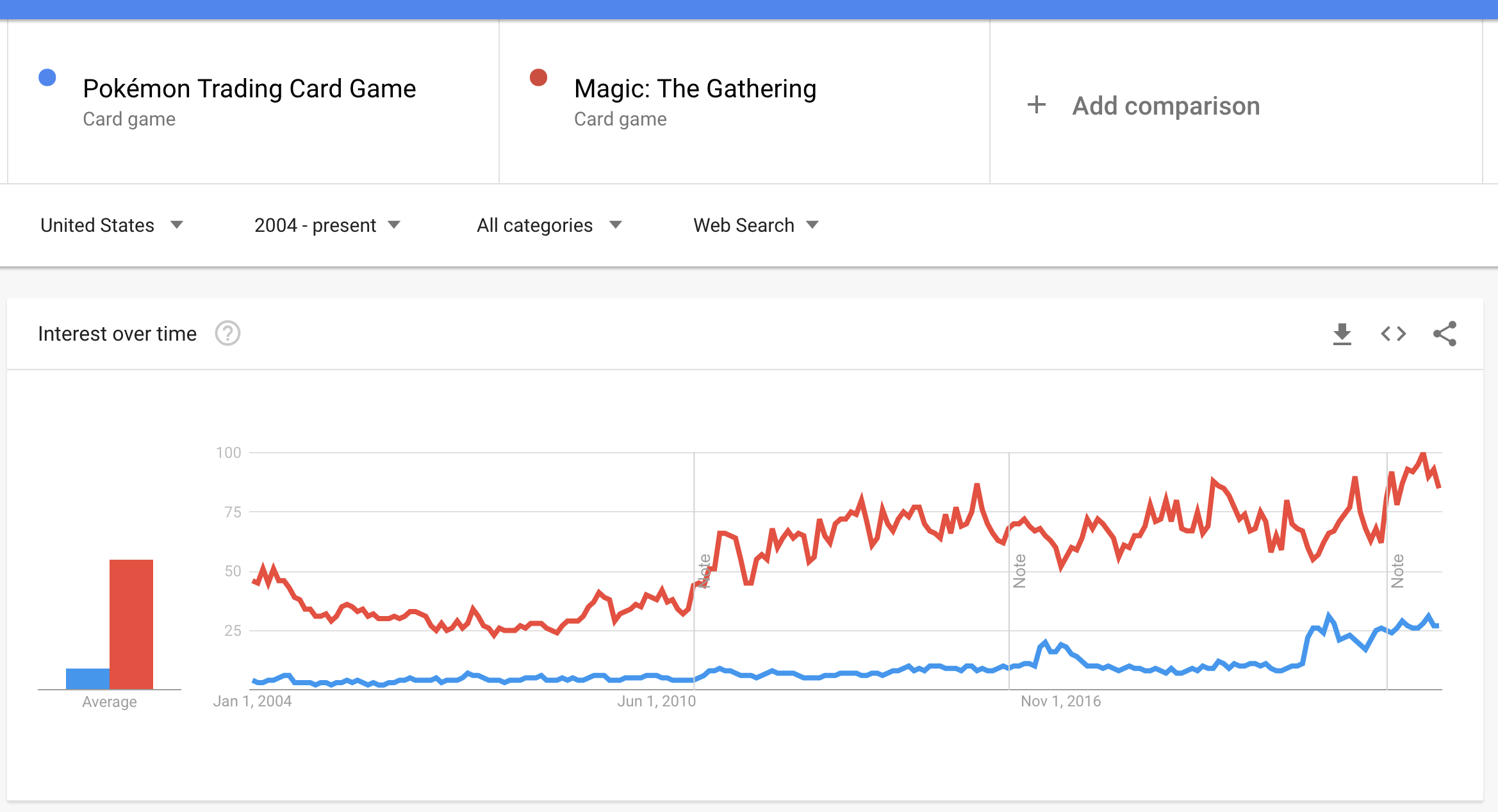

I can also use Google Trends to do research

Is the Sky Falling?

No. While there are, of course, many concerns about Magic: The Gathering and the decisions that Hasbro has been making, the Bank of America report seems wholly fixated on Magic as an investment product, not as a consumer product. This is not a new idea. For as long as I’ve been writing about Magic (10 years) there have been members of the community arguing that the long-term value of products in the secondary market (investing) is required for the health of the overall game.

In the past few years, dating back to before the pandemic, Wizards has decided to test that theory. To say this is a new idea isn’t accurate because you can trace the origins of these decisions back to Modern Masters, in 2013, a product which put Wizards on the course of printing products for the express purpose of trying to reduce secondary market prices and lower the financial barriers of entry into the game.

Hasbro is not perfect. And the author raises many strong concerns. Is player growth sustainable? How will they deal with the inevitable decrease in revenue once the pandemic boost vanishes (and is replaced by inflation)? Why are foils still curling like Pringles? But the rest of the report falls short of what I would call a “deep dive” into the game’s business, and at times stretches the factual evidence to try to support their core claim that lower secondary market prices, and fewer investors in the market, will directly translate to reduced revenue for Wizards.

The first page of the report highlights things that obviously resonate with the community. 30th Anniversary Edition is overpriced and poses a risk to collectors. Product fatigue is absolutely real and players are sick of hearing “this product isn’t for you.” Retailers are struggling to figure out how to properly stock their shelves amidst changing distribution pipelines, shipping concerns, consumer sentiment, and product schedules.

But make no mistake, the rest of the report does not adequately perform a deep dive into those issues, instead relying almost entirely on the value of collectors booster boxes and specifically tailored Google trends to support an argument that is as old as the game itself. Do investors or players drive the value of Magic products? The author of the report is betting on investors, and Wizards seems to be betting on players.

Who would you bet on?

Rich Stein (he/him) has been playing Magic since 1995 when he and his brother opened their first packs of Ice Age and thought Jester’s Cap was the coolest thing ever. Since then his greatest accomplishments in Magic have been the one time he beat Darwin Kastle at a Time Spiral sealed Grand Prix and the time Jon Finkel blocked him on Twitter.