It’s a frigid March night on Monomoy Island, a sandy strip between Cape Cod and Nantucket. The year is 1902, with a northeastern gale rattling the doors of the lighthouse. A report comes in of some ships lodged on Shovelful Shoal, preventing them from reaching land. This stirs the men of the US Lifesaving Service into action. Eight men wheel a heavy wooden lifeboat out onto the sand, and take off toward the waves crashing in the darkness. Waxed canvas raincoats offer some protection from the elements, but the chill has a way of finding the skin. The task is to bring the stranded sailors back to shore, before the storm swallows them all. Their unofficial motto is “You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.” Eight go out to sea; only one returns.

As long as people have been building ships, the sea has captured the imagination. It’s a seemingly infinite expanse, the backdrop for stories of triumph, loss, and the allure of the unknown. Today, we look at Magic’s depictions of life on the sea, and how it supports the worlds we visit. We’ll look at life on the shore, seafaring, and what lies beneath the waves.

Rishadan Port by Jerry Tiritilli

Seaside Life

To understand the port and its inhabitants, we need to look at its geography. The port is more than just the meeting of the land and sea. It’s the confluence of various groups, with different motivations and goals. All of these narratives play out in one place, where the ships come to rest.

Down by the water, commerce is the main order of business. To an inland visitor, docks are where goods are unloaded from faraway lands. However, locals know that some goods are more closely-guarded than others. The Customs Depot might be a source of corruption, as smugglers look to have their shipments go untraced. These shipments might be weapons from an Arms Dealer, items under Embargo, or even Stolen Goods pilfered by pirates. Some officials might be more wise to the underworld, resulting in a Dockside Extortionist that shakes merchants down for a heftier payment.

Rishadan Cutpurse by Christopher Moeller

Away from the noise of the docks, the port city has its own behavior. With a mixed population of travelers and locals, crime is a more attractive opportunity. These dynamics play out at a Rishadan Port of Mercadia. Tight alleys make an easy escape route for a Rishadan Cutpurse. After night falls in the city, lost travelers are easy targets for a Cateran Persuader. With an escape to sea being only a few blocks away, a port can be a hotbed for criminals that disappear over the horizon.

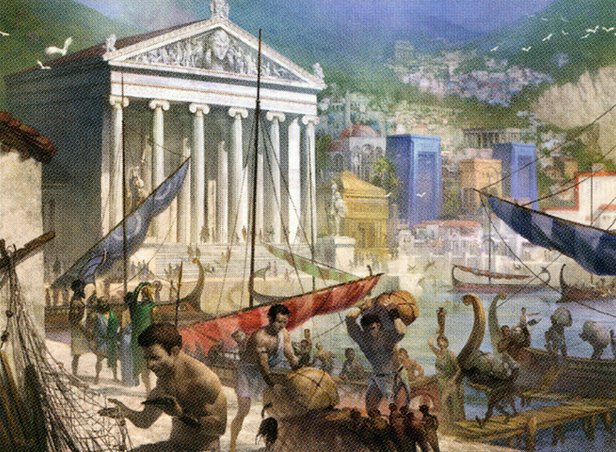

Temple of Enlightenment by Svetlin Velinov

Aside from business, a coastline plays an important spiritual role with its residents. In Svetlin Velinov’s rendition of seaside Meletis, we see commerce and religion coming together in one place. Merchants know to keep to their schedules, but they can’t pass on making an offering to Thassa, God of the Sea. These rituals, generally done to grant safe passage, are common in the folklore of ancient seafaring nations. Mike Sass’ Aerie Worshippers pulls inspiration from ancient Roman augurs, looking to seaside birds for signals from the gods. Meanwhile in Kaldheim, Donato Giancola’s Funeral Longboat depicts the Norse practice of releasing the dead out onto the water, to disappear into the fog on the horizon.

Funeral Longboat by Donato Giancola

It’s not unusual for ports to be so entwined with religion. Going as far back as 6th century AD, the Chinese port of Quanzhou was a confluence of religious travelers from around the seafaring world. Practicing Buddhists and Taoists, intermingled with Muslims, Catholics, Hindus, Jews, and Manichaeans. Wherever large groups of people come together, so do their beliefs. Quanzho served as an important hub to the Maritime Silk Roads, a real-life reflection of colorful port cities depicted in Magic.

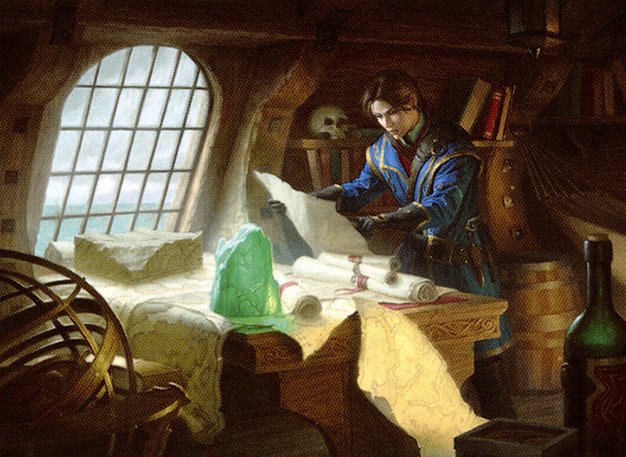

Chart a Course James Ryman

Seafaring

The crew is picked, the supplies are stocked, and the course charted. Ahead lies nothing but the horizon. The vast expanse of water is a canvas for the stories of heroes and villains alike.

Often depicted as somewhere between hero and villain, pirates land as compelling characters that are easy to root for. Pirate Ship was the first pirate creature in Magic, all the way back in Alpha, despite not showing any discernible pirates on board. Years later in Portal Second Age, we were introduced to the Talas, through cards like Talas Warrior and Steam Frigate. This expanded upon the narrative of marauding bandits on the high seas, but this time bringing black powder weapons into the mix.

Admiral’s Order by Slawomir Maniak

The arrival of Ixalan in 2017 ushered in a new era for pirates in Magic. The likes of Admiral Beckett Brass and Captain Lannery Storm gave Magic players the Hollywood image of a pirate in the Americas. Slawomir Maniak’s Admiral’s Order, Ixalan’s version of “Cancel With The Set’s Mechanic”, puts us in the shoes of Brass’ crew, as they heave themselves across the waves. It’s the pivotal moment in pirate fiction, one that pulls the viewer from a place of safety, into a rage of gunpowder smoke, clanging swords, and splintering wood.

Blaze by Qu Xin

A pirate’s bravado is easy to admire, but seafaring is also a foundation for the pursuit of power and dominance. Those who control the water can control travel and trade. This leads to large scale conflicts, like those depicted in Portal Three Kingdoms. In Jacob Torbeck’s piece about Vito, Thorn of the Dusk Rose, he describes the analogs between vampire conquistadors and Spanish involvement in Mesoamerica. All the trappings were there in Ixalan, with a visiting power coming to shore in a foreign land. While Magic’s visual storytelling can control the narrative that plays out in the cards, we can never fully separate the imagery from the shadow of Europe’s colonial history.

Seeker’s Squire by Anthony Palumbo

Language is important when recognizing the real world context of these characters. When you have a card like Seeker’s Squire with the Explore mechanic, it centers the narrative around the visitor mapping out the space for those that come after them. They’re taking what is unknown to their nation, and creating something tangible from it. Whether on land or water, the concept of exploring is rife with colonial undertones. Are they truly discovering new places when there are inhabitants already living there?

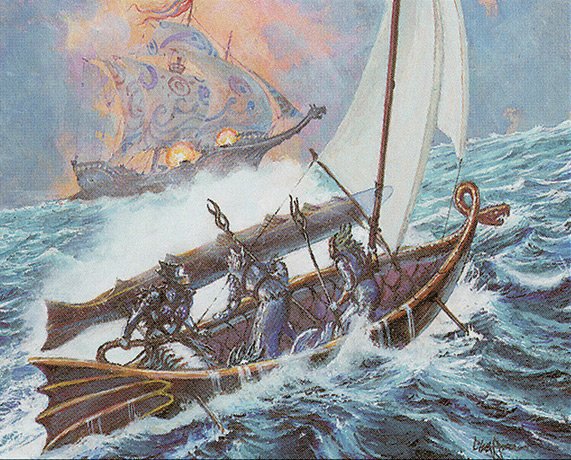

Saprazzan Outrigger by Doug Chaffee

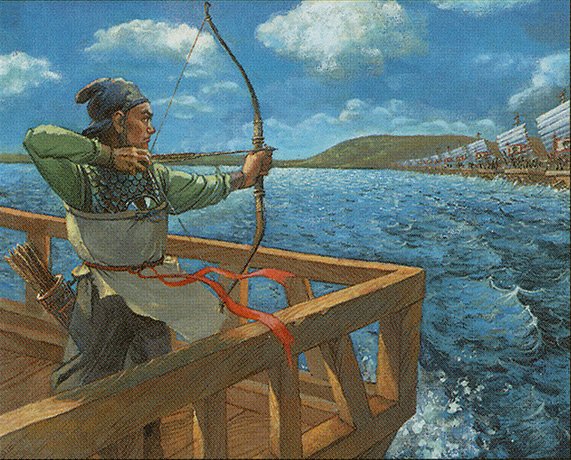

While sets like Ixalan and P3K show us the seafaring of large naval powers, other spots in Magic’s history give us images of those with a closer, more intimate relationship with the sea. Smaller ships bring stories of those defying the odds out at sea, instead of those looking to conquer it. In Doug Chaffee’s Saprazzan Outrigger, the merfolk of Saprazza are looking to outrun a much larger Rishadan ship. Their outrigger canoe, rocked by cannon fire, has structural elements similar to those used by ancient Austronesians to travel around the South Pacific. This kind of vessel also shows up in Christopher Burdett’s Ancient Carp. Seeing that they’re smaller and lighter, they require advanced sailors to pilot them. The ancient Polynesians are known to navigate using the stars and ocean swells, despite not having compasses like the Chinese.

Wu Longbowman by Xu Tan

With depictions of smaller vessels, we’re allowed a closer look at an individual’s experience on the water. For this article’s cover piece, Jerry Tiritilli’s Lingering Mirage, we’re brought right into the struggle of the lone sailor. They appear to be lost during a fishing trip, left wondering what their surroundings are. With their small craft, they’re at mercy of the ocean’s larger swells. If the sea doesn’t take them first, their mind might.

The sea presents both danger and opportunity. However, the balance shifts once we go beneath the waves.

Nehezal, Primal Tide by Sam Burley

What’s Found Beneath the Waves

Around the world, seafaring cultures have folklore on what lurks in the deep. In Japan, legends tell of the Umibōzu, a malevolent spirit that can be responsible for rough waters and sinking ships. In Māori mythology, the Taniwha is a dragon-like creature that can be either a monster to travelers or a guardian to a particular tribe. For the Greeks, Homer’s Odyssey involves Odysseus navigating a narrow strait between the monsters Scylla and Charybdis. Finally, in American literature, Herman Melville’s Moby Dick depicts a Colossal Whale that can crush ships in two. These stories are meant to instill fear and wonder, as seafarers are called upon to respect the waters they travel.

Dandân by Drew Tucker

In Magic sets that depict the ocean, sea monsters represent a great equalizer. Seafarers are not the top of the food chain, but rather a passing traveler that’s hoping to avoid becoming lunch. Ships provide a sense of scale in art, just like birds might be used for a giant standing above the treeline. Richard Wright’s Kraken of the Straights demonstrates this on a relatively small scale, with the kraken lurking beneath a single trireme. Meanwhile, in Eric Deschamp’s Wrexial, the Risen Deep, ships are tossed like toy boats in a bathtub. In a high fantasy world of seafaring, ships are never the biggest thing in the water.

Vodalian Hypnotist by Rebecca Guay

Not everything below the waves will eat you, though. Instead, some might put a trident in your chest. For thirty years, merfolk have been one of Magic’s most enduring creature types. They can be depicted with either humanoid legs, or having a more fish-like lower body. Several cultures around the world have folklore of the people under the sea, from the South China Sea to the northern waters of the Baltic.

It can be easy to draw parallels to humans that walk on land, however there are some key differences at play. Merfolk in Magic demonstrate an intimate connection with their natural surroundings. Meanwhile, humans can often seek to dominate their landscape, instead of playing a part in it. In my piece about life on the plains, this plays out in sprawling city states like Benalia, who have grown past their humble beginnings to seek conflict and expansion.

Coralhelm Guide by Viktor Titov

Flavor texts like Coralhelm Guide illustrate a merfolk’s deep knowledge of the waters they live in, regardless of their nation’s prominence. Also, a merfolk shows a sense of responsibility to the ocean, acting as protectors towards those that venture too close. In Triton Shorestalker, we see a merfolk taking the encroachment of humans into their own hands. Humans are a bit more reckless with how they treat their land, as evidenced by Geomancer’s Gambit. Despite these differences between humans and merfolk, they cross paths in various corners of Magic, some encounters being quieter than others.

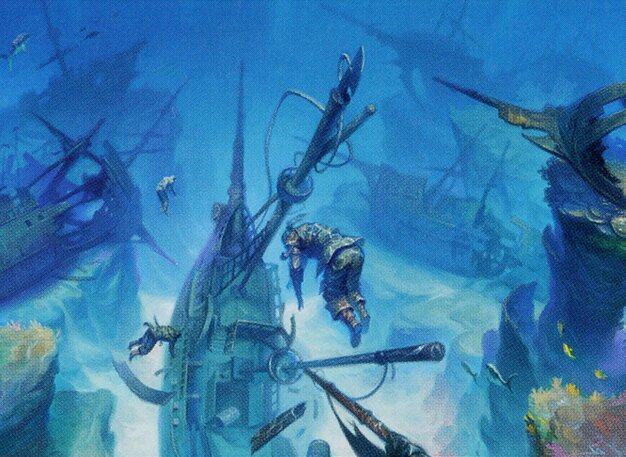

Watery Grave by Victor Adame Minguez

Not every seafarer makes their way across the water. Areas with rough weather, or hidden rocks, collect the remains of ships and sailors alike. They’re destined to slowly become one with the environment around them, with certain trinkets surviving in the icy depths. Treasure seekers like Seafloor Stalker flock to shipwrecks or sunken ruins, in search of riches long forgotten. This is a one-sided relationship that merfolk have with humans, reclaiming the items that are no longer needed.

The Horizon Calls Ever More

When we look out to sea, are we looking at anything particular? Rather, are we looking into ourselves instead, at what the sense of adventure instills in each of us? The sea shows us what people like us are capable of, despite slashing rain, heaving waves, and things that watch from the depths below. For those reasons, it’s a foundation for some of Magic’s most compelling creatures and settings. The sea is for those who push off from shore and head into the unknown, because you don’t quite know what you’ll find on the other side.

Travis Norman (he/him) is a writer and photographer from the wooded foothills of New York, currently living in South Carolina. He plays nearly every Magic format, but has a special love for Legacy, Premodern, and Canadian Highlander. He has loved Magic since Starter 1999, but he champions having a healthy mental and financial relationship with the game. When not playing games, he enjoys cycling, tea, and dog parks. You can follow his exploits here on Twitter and Instagram.