Cover image: Abiding Grace by Jenn Ravenna Tran

As a professor of theology and religious ethics, I believe that there is value in understanding what religions teach and how those teachings impact peoples’ lives and cultures. As a religious person, I’m also deeply invested in reckoning with how my religious tradition and those I encounter affect me personally and the folks I love—and it’s hard to turn this off. For some folks, Magic: The Gathering is a needed escape from these heavy questions; but for me, Magic and especially its lore are a playground in which these issues can be played with and poked in a way that is insulated, at least some small amount, from the higher stakes of critique of a real religious tradition.

Where do I see this happening most fruitfully? So glad you asked. Here are my rankings for the top 10 religious institutions in Magic’s multiverse that I think have the most to say about contemporary issues in (western) religion and spirituality:

10. The Machine Orthodoxy

Due Respect by James Ryman

This universalist evangelical movement ostensibly welcomes mana of all colors, as long as the white mana is in charge. The Machine Orthodoxy just wants to purify and compleat you, and if it has to do that by colonizing other worlds and forcing you to comply with groupthink, then that’s what it will do. Really, it’s no trouble.

The Machine Orthodoxy is an obvious and monstrous evil reminiscent of Star Trek’s Borg. The terrifying Giger-esque New Phyrexians are our projection of fascistic terror, with all its promised disintegration of individuality. The villainous eugenic aim of Yawgmoth and his worshippers has been brought forward and twisted into the dream of even greater multiversal domination.

Part of this twist is the relentlessly literal and materialist mind of the New Phyrexians, who have only recently begun to understand what a soul. There is something fascinating about how Phyrexians receive and understand information—like anyone, according to the structures of possibility within their own worldview. As the medieval dictum goes, “what is received is received in the mode of the receiver.” Nevertheless, the alien nature of the New Phyrexians is distancing enough that I’m more interested in the Old Phyrexia.

9. Priesthood of Yawgmoth

Phyrexian Scriptures by Joseph Meehan

That’s right, “GIve me that ‘old time’ religion.” On “Old Phyrexia,” Yawgmoth came to have the power of a god, and that included having followers! If you like H.R. Giger-esque body horror (I do not) and eugenics, and/or listening to Fear Factory, this might be the place for you.

The design of Phyrexia and its scriptures is inspired by the Christian mythology surrounding Hell, where Yawgmoth is considered the great creator and the spheres of Phyrexia are patterned after the layers of Dante’s Inferno. The scriptures, which appear on the eponymous card and in the flavor text of six cards, read the way one may expect a religious text to read. The flavor text on Dark Ritual is represented below, in Joseph’s Meehan’s rendering:

From void evolved Phyrexia. Great Yawgmoth, Father of Machines, saw its perfection. Thus the Grand Evolution began.

Evil cults are often meant to be readily understood as villains, and we aren’t meant to think too much about them, but there’s something here about the notion of transhumanism and our faith in science and medicine to solve our problems and carry us forward that might be worth teasing out.

Find more about Phyrexia at: “The Grail Legend in Magic Lore”

8. The Church of Tal

Preacher by Quinton Hoover

Do you want a mishmash of everything Jesper Myrfors wants to critique about Christianity? This Church is for you—it’s got everything: Inquisition, a Fire and Brimstone Preacher, and likely references to antisemitic violence. Whatever it may have once been before the Brothers’ War, The Church of Tal became a devoted witch-hunting institution in the centuries after the Sylex blast, adopting the credo “Suffer not a magician to live” almost verbatim from the planeswalker King James’s Bible.

Given the Church’s history of reacting against the immense violence of artificers and wizards, there’s probably something interesting to say here about the danger of the oppressed becoming the oppressor, but the Dark wasn’t yet ready to say it.

Read more about Magic & Witch Hunting at “Religion & Horror in the Season of the Witch”

7. The Farrelite Cult

Have you ever gotten so upset over religious complacency that you founded your own massively popular breakaway sect of zealots and doomsayers which elevated you to such prestige that you were able to convince an eternally young woman to have an affair with you, only to have her leave you for a Sarpadian dwarf, so you decided to tell everyone she was the reincarnated high priest of the evil dark lord of a different religion, and sent your former concubine to go and kill her, not realizing that your intended victim’s brother had godlike magical powers and could incinerate you? Well that’s what it feels like to drive the new Ford F-150.

The Farrelites were a charismatic cult of personality, preaching the end times, demonizing their enemies, and waging a culture war within Icatia, all while the cult leader manipulated women within his sphere of influence. Can someone go check on whether they ended up making Icatia great again—it’s gone? Oh. hm.

6. The Orzhov Syndicate

Revival by Paul Canavan

Ravnica is what you get when you think to yourself, “wow, what if every church in Prague was actually the architectural style for the whole world.” The Orzhov Syndicate is what you get when you reduce 16th century Catholicism to the doctrines of purgatory and indulgences and the material excesses of clergy and make it an entire church’s personality. The resulting institution functions something like a mob or a crime family, which the wealthy extorting the weak and less powerful, and binding them to contracts that they will likely never repay.

Like Innistrad’s Church of Avacyn, what started out as a two-dimensional portrait of a Church run like a shady bank later becomes an idea for at least a faint consideration of deeper issues. When Kaya kills the Obzedat and assumes leadership of the guild, the notion of debt, penance, and reparation are briefly raised, and the confluence of the spiritual and the economic set the stage for some potentially worthwhile reflection on how money and faith interact. The story during the WAR era didn’t quite get there, but perhaps next time.

5. The Legion of Dusk

Vito, Thorn of the Dusk Rose by Lie Setiawan

Another take on 16th Century Catholicism. If doing a “what if” with indulgences and purgatory wasn’t enough, the Legion of Dusk on Ixalan seemingly compares the Spanish Catholic conquistadors to bloodthirsty vampires. But wait, they aren’t really conquistadors…

I mean, sure, they’re pale and they dress in clothing and armor styled after the 16th century. They have Spanish names, and sail galleons across the seas from their homeland—and admittedly, they do have hostile encounters with the natives. But they aren’t really colonizing anything. Adanto is just a temporary thing while they look for the Immortal Sun. We promise! We also promise they aren’t Catholics. Yes, they apparently have a supreme pontiff, and they build cathedrals and practice a kind of baptism and the consumption of a sacrament in honor of their founder. But look, it’s not like they said that Catholics are bloodthirsty, colonizing fanatics.

Caricatures aside, the stories of the Apostle Mavren Fein’s epiphany upon finding Elenda, about how the purpose of their faith has been twisted and misunderstood in her absence, and about VIto’s resistance to this news, has resonances with the experience of many young religious people who begin to see the world and their old faith with new eyes (or those who refuse to) after leaving home for the first time. Whether we explore this further in the coming year’s Ixalan set is yet to be soon, but I hope we do!

Read more at: “The Thorn in Our Side: Vito & the Legacy of the Spanish Conquest”

4. Amonkheti Faith

Basri, Devoted Paladin by Jason Rainville

Have you ever spent your life training to be worthy of special service to your gods so you could pass the test and go to the afterlife, but in reality your gods had been dominated generations ago by an immensely powerful dragon wizard from another world in an elaborate plot to create an unstoppable army of undead super soldiers so he could invade a different world and reclaim his lost immortality? Well that’s that it feels like to drive the new Ford F-150.

Amonkhet’s population is the victim of a different sort of pyramid scheme, a sham religion replacing their original, indigenous faith. Using their old gods, who seemed to be genuinely concerned about the ideals and concepts they represent and embody, Nicol Bolas twisted the Amonkheti’s understanding of spirituality to funnel power to himself, manipulating the beliefs of the Amonkheti for his own dark purpose.

This story is common enough in American culture: a strong personality tweaks Christianity just enough to walk away with the riches of their congregation while still maintaining all of the appearance of being a religious expression concerned with the spiritual well-being of its members and even still perhaps possessing ministers who are serving from genuine and benevolent conviction.

While we haven’t gotten to see him in action in the story, yet, Basri Ket is a fascinating example of someone healing from the spiritual loss that is felt when a religious community is rocked by scandal and the revelation that so much of what they believed was a distorted fabrication. What Basri Ket does in the wake of this knowledge is to separate enduring truth from its abuse by demogogues. Taking up Oketra’s ideal of solidarity, Basri begins a new faith that aims at something transcendent without reliance upon the falsified cosmology of the Amonkheti religion—a tremendously fascinating approach in an era where more and more people in developed nations are disaffiliating from organized religion while remaining as spiritual as they ever were.

3. Therosian Faith

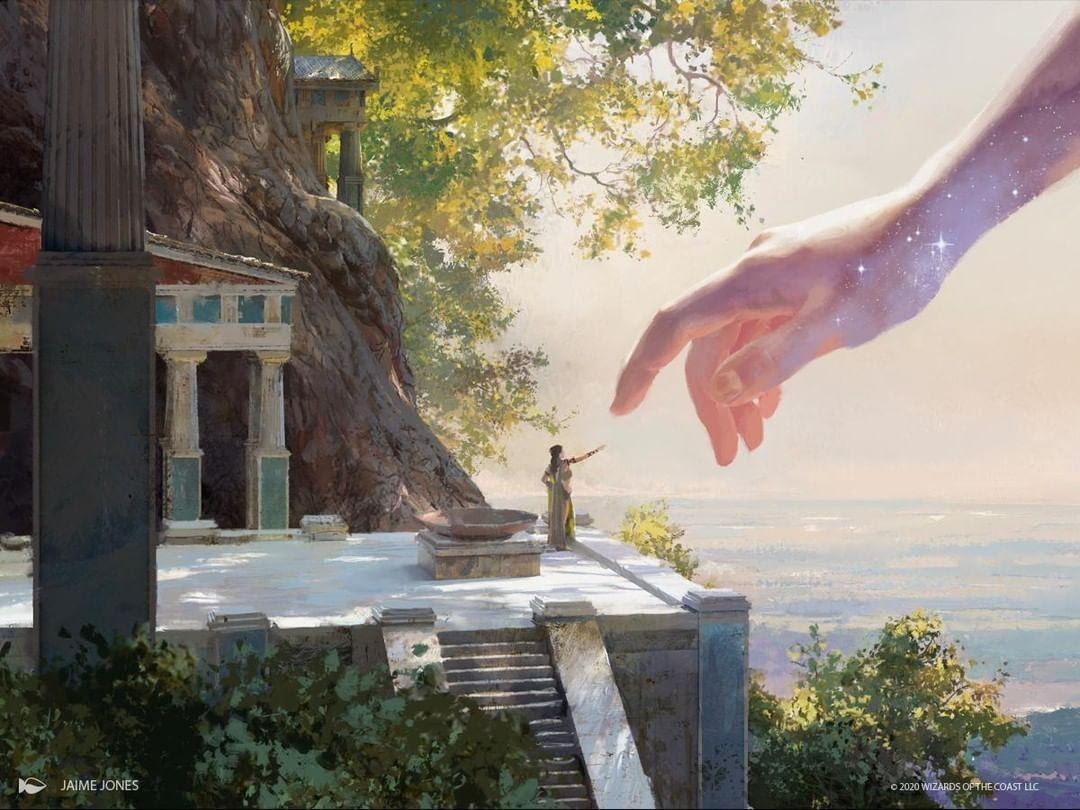

Idyllic Tutor by Jaime Jones

If the poems, dialogues, and philosophy we have from Ancient Greece is any indication, the Greek Gods were, for layfolk, almost never gods of exclusive devotion (henotheism) until very late (4th to 2nd centuries BCE). However, being in any sense devoted to Heliod, as a pilgrim, champion, or priest would certainly cause consternation. In the wake of rumblings about Heliod’s actions regarding Elspeth, and with whispers mounting that “gods are the patterns that we perceive,” given sentience, there are few places in the multiverse that are likely to have more lively conversations about philosophy of religion.

What is the power of collective belief? Can collective belief become so strong that it develops something of its own will and life? Is that (all) what religion is? Is that the truth of religious doctrine? If that’s the case, then what is apotheosis (ascending to godhood), really? Is it giving oneself over so fully to the collective belief that one’s name becomes symbolic of, even synonymous with some primal force? Like Fred Rogers, and kindness? The way the world of Theros provokes theological questions like these is why I’ve ranked it at number 3.

Read more at:”Reflections on the Return of Idyllic Tutor”

2. The Church of Serra

Abiding Grace by Jenn Ravenna Tran

If, for your mental health one day, you need to daydream about a religion that is everything it says it is, an institution dedicated to the teachings of its legitimately benevolent founder, that sets out to protect the weak and help those in need, then the Church of Serra might be for you. This Church’s floating towers are a little piece of heav—er, Serra’s Realm on Dominaria.

The Serran Church preserves a lot of the aesthetics that we expect in Christianity-inspired fantasy churches, like glorious stained glass, takes it to the next level, and sets it within an institutional structure wherein the strongest authority figures all take the form of strong, flying women. If the current Church is keeping the old traditions of Serra’s Realm alive, then it also has hymns and liturgy! High Church Anglicans rejoice!

Idealistic depictions of institutions like this one help us to imagine what’s possible, to put our hopes and aspirations into a form where we can examine and improve them, and learn from our own narratives about our motivations and our goals. While having too rosy an idea of any institution can blind us to inequities and other moral failures, not pausing to imagine a better world can tempt us toward an unhelpful nihilism. The goodness of the contemporary Church of Serra is a gleaming respite from the often depressing examples of religious institutions elsewhere.

Read More at “The Church of Serra”

1. The Church of Avacyn

Arlinn, the Pack’s Hope by Eric Deschamps

“Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.” —Karl Marx, Critique of the Hegelian Philosophy of Right, 1844

What if we made Marx’s words about religion the entire plot of a Magic: The Gathering set?

Seriously though, while the initial premise of Innistrad’s main institutional religion could seem like it leans into a thin literalization of Marx’s critique, recent visits to Innistrad hint at the possibility for deeper reflection about how to hold on to faith and rebuild after the institution is rocked by corruption and scandal, or after your relationship to yourself puts you at odds with the beliefs of many in the Church (cf. Odric, Thalia, and Arlinn).

Now that the Church is rebuilding and many folks are turning to Sigarda, and folk religions are returning in the absence of the Avacynian Church’s persecutions, the religious landscape on Innistrad is poised to become one of the most interesting places in the multiverse to ponder issues analogous to contemporary real-world religious issues—which is why I’ve given it the top spot!

Read More at “As Hallowtide Approaches: Negotiating Faith and Festival”

I hope you’ve enjoyed this tour of different religious expressions in the multiverse. There are so many more religious or quasi-religious institutions we might have examined, and in more detail, that I’ve omitted for a lack of lore, or because they land in an area that is far enough outside of my expertise that I didn’t think I could fairly articulate the issues they raise. If these 10 provoked any deeper thinking, then I’ve done my job, and I am happy to leave the rest to you for now.

Until next time.

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.