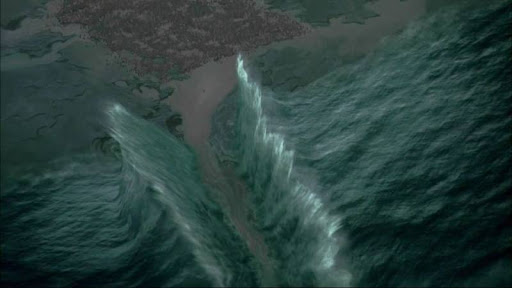

Cover image: Revelation by Kaja Foglio

Readers of Magic and Meaning will already know that one of the premises of this column is that through the use of images and symbols taken from real world religions and cultures, Magic: The Gathering does real theological and philosophical work in its cards and associated narrative, whether intentional or not. In the case of unintentional theological work, we have sets like Limited Edition (Alpha / Beta), which reference the trappings of medieval religion as a means of world-building through symbols already familiar to the players.

Religious imagery we recognize becomes a shorthand that we can interpret through our pre-loaded associations with those symbols and their prior use in fantasy media. While the creators may intend nothing other than the aesthetic resonance of the symbols, they nevertheless reiterate and repurpose them in ways that make statements with and about them. On the other side, we have sets like The Dark, which was intended, according to Jesper Myrfors, to critique organized religion and to complicate the picture of religion that the original Magic sets had established: a bastion of justice and healing can, taken to vicious extremes, become an oppressive persecutor of difference.

Sometimes, however, early Magic seemed to drop the pretense of world-building altogether, and sought not merely to cite real world symbols, but to represent scenes or reproduce text from real world religion and folklore. Arabian Nights and Portal Three Kingdoms are the two most plain examples of this; but for today’s piece, I wanted to take a brief look at cards from another set that leans into this form of citation, 1994’s Legends. Specifically, I want to look at the seven cards that most obviously seem to reference stories from the Bible.

Greater Realm of Preservation depicts an angel guarding the paradise of Eden, from Genesis / Bereshis 3: “He drove out the man; and at the east of the garden of Eden he placed the cherubim, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to guard the way to the tree of life.” (RSV) In the television adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s Good Omens, we see Michael Sheen’s “Aziraphale” give the sword to the humans out of pity.

Like Neil Gaiman and Michael Sheen’s portrayal of the guardian of Eden, Nene Thomas’s version isn’t quite what’s described in the text. The cherubim (plural) mentioned in the text are the four-faced, six-winged celestial beings that are elsewhere (cf. Ezekiel 1:15-21) described as accompanying ophanim—the many-eyed wheels more popular in memes about “biblically accurate” angels.

The sword, likewise, seems to move about on its own, like Dancing Scimitar, in the biblical narrative. Gaiman and Thomas are hardly alone, however—the entirety of European Christian art history depicts this the same way they do, rendering the scene far less strange than ancient Jewish authors intended.

Aziraphale bequeaths the flaming sword to Adam in Good Omens.

The card may not be amazing by today’s standards, but it’s certainly “colorful.” This card is a likely reference to a story from later in the book of Genesis, from chapter 37: “Now Israel loved Joseph more than all his children, because he was the son of his old age: and he made him a coat of many colors.”

This story, in which Israel’s favored son is sold into slavery and rises through divine providence to govern Egypt, sets the stage for Moses’s liberation of the Israelites throughout the next two books of the Torah, and is the inspiration for Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat,” an absolute classic of musical theatre and/or peak cringe.

If someone were to put this Dream Coat into an old school deck, you’d be using it to get around protection or to make a creature vulnerable to color-sensitive effects like Terror, Red Elemental Blast, and so on—effects plentiful in early Magic.

Joseph interprets Pharaoh’s dreams in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Coat.

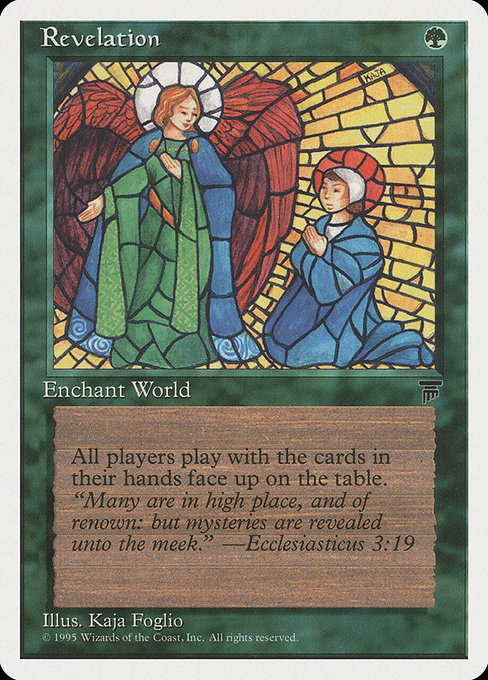

Part Water depicts a mage taking a page from the book of Exodus, and parting the waters, enabling a caravan of Israelites and/or your creatures to pass through unhindered by Pharaoh’s chariots. Even the flavor text helps out here, citing a salient line from the story. One of the best depictions of this story in contemporary media is from DreamWorks’ Prince of Egypt (1998), an often overlooked animated feature which does a phenomenal job telling the story of Moses’s early life up to the Israelites’ liberation from Egypt.

The Parting of the Red Sea in Prince of Egypt.

Historically, Nebuchadnezzar was a great king of the Babylonian empire, who laid siege to Jerusalem and deported many of the residents of Judah to Babylon. The Biblical narrative of Daniel recapitulates the story of Joseph referenced on Dream Coat, in which the hero (Daniel) is an exile from a foreign land who must interpret the ruler’s dream, and is subsequently richly rewarded.

On this card, we see the power of “divination” or “dream interpretation” reflected in the ability to learn hidden information about the future and possibly avoid certain outcomes. The masterful artwork by Richard Kane Ferguson bolsters the dreamlike quality of the card, as the Babylonian ruler’s cloak seems to blend into the waves of the background, and his eyes stare hauntingly at the viewer.

Revelation is such a strange card, in so many ways. One would think this card would be blue because of its effect, but it’s green. With a name like “Revelation” one may have expected a scene from the apocalyptic book of Revelation, but instead we get Kaja Foglio’s gorgeous depiction of the Annunciation, from the first chapter of the Gospel of Luke. The flavor text, however, is pulled from Ecclesiasticus, also known as the Wisdom of Ben Sira, or simply Sirach—interestingly not Ecclesiastes, as the Legends printing says.

The result is a card that is expressing a theology. The juxtaposition of this image, text, and cardname are combined in a theological deep cut. Shortly after this scene in the beginning of Luke’s gospel, Mary will echo the sentiments of the scribe Ben Sira when she sings: “For he hath regarded: the lowliness of his handmaiden . . . He hath put down the mighty from their seat: and hath exalted the humble and meek.” (Lk 1:48,52). The scene Foglio paints is indeed, for Christians, a moment of revelation.

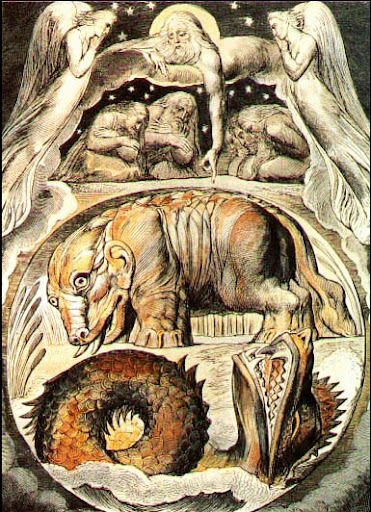

I’ve mentioned the Book of Job before as a source of rich inspiration for fantastic monsters, and here on Segovian Leviagthan we see it quoted directly. Leviathan is the aquatic sister of Behemoth, two indomitable ancient monsters that the G-d of Abraham reminds Job he created. In the book of Job itself, the monsters don’t do anything in particular, but are cited as proof that divine power transcends human knowing. The might of Leviathan is praised over ten short verses, culminating in the question to Job, “[If I have made monsters as powerful as Behemoth and Leviathan], who then is able to stand against me?”

The verse quoted on Segovian Leviathan is the first of the ten praising Leviathan’s great might. Legends uses the verse numbering from the Hebrew text, while later versions would list the verse according to the usual number (Job 41:1) in Christian bibles. The Segovian Leviathan is perhaps only dubiously deserving of such words (though the art does depict it as utterly massive); a few months later, the Dark’s Leviathan would put every prior creature to shame for sheer size.

Behemoth and Leviathan, watercolor by William Blake from his Illustrations of the Book of Job (1826).

Years later (by the Duelist issue 25, in 1998, anyway), the Segovian Leviathan’s small size would become the basis for the lore about the plane of Segovia, a plane where everything is miniature by comparison to other planes. The Segovian Leviathan is thought to be the largest creature on the plane.

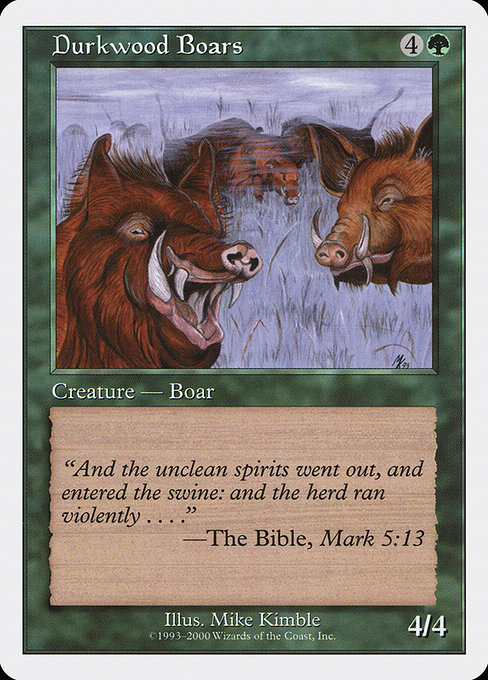

Sometime prior to 1,600 BCE, many cultural and religious institutions in the Ancient Near East developed a pork taboo—strange, considering that the Canaanite deity, Baal, was associated (favorably!) with a wild boar. How did a divine animal go from dietary staple and acceptable temple sacrifice to forbidden food?

Archaeologists and historians speculate that sometime around the end of the Bronze age, the association of pigs with filth and the poor began to turn people against raising and consuming swine. When ancient Hebrews came into contact with the Philistines around 1200 to 1,000 BCE, the pork taboo in Ancient Hebrew Religion (proto-Judaism, if you like) may have moved beyond a “class” marker and become an ethnic marker.

By the time Leviticus was written, in the 7th or 8th century BCE, this taboo was inscribed as a legal and religious marker for the southern kingdom of Judah, strengthening and crystallizing as struggles between pork-abstaining Jewish people and pork-consuming Greek conquerors reached their most violent points. Certainly, by the time the Gospel of Mark was written, Jewish people saw swine as unclean animals, associated with religious and political oppression as well as physical and ritual impurity.

Why is this relevant? For the flavor text on Durkwood Boars, Legends uses the story of Jesus casting “unclean spirits” (demons) that called themselves “Legion” out of a possessed man, and into a herd of swine. The pigs—now doubly unclean—stampede, rushing into the sea and drowning.

The use of this flavor text on Durkwood Boars suggests the wild, dangerous charge of the demon-possessed pigs, giving us the impression that the boars of Durkwood are nothing to mess with. In 1994, at 4/4, they’d have run right over Grizzly Bears, Giant Spiders, and War Mammoths, and could go toe-to-toe with a Serra Angel if one was to be assigned to block them.

Worldbuilding Through Allusion

With the exception, perhaps, of Revelation, Legends’s overt references to Jewish and Christian scripture are perhaps among the most banal references to real-world religion and philosophy in the game. Compared to the inquisitors and witch hunters of The Dark, the indulgent prelates of the Orzhov Syndicate on Ravnica, the “opiate for the masses” of the Church of Avacyn, or the vampiric conquistadors of Ixalan; these Biblical references offer little in the way of commentary, instead providing mostly face-value depictions of figures and scenes from sacred scriptures. Most of early Magic’s references to religion are just this: citations of familiar stories, rendering the multiverse of Dominia a pastiche of real-world mythoi.

Herein lies what I speculate the inclusion of these references to real-world religions’ stories must have meant to the designers: that these sacred narratives have a place alongside other literature from the past, and not above it or below it, insofar as it remained fair game for use in a fantasy card game. Like Arthurian legend, the Bible is at once ancient enough to evoke a sense of the fantastic and mythical, but familiar enough to be easily interpreted by a wide audience.

This is worldbuilding by analogy and allusion. “You see this sea monster? It’s like the Leviathan. These boars? Remember the story where Jesus cast demons into swine? Yeah, imagine that!” Without some religious literacy, the full context of the card is lost, but in most cases, they remain legible game pieces, and not often as complicated as other early Magic Cards.

Like Limited Edition (Alpha & Beta), Legends is a set that engages in worldbuilding through the presentation of a panoply of evocative images, a shifting mosaic of creatures and locations and spells without an accompanying narrative. The multiverse of Dominia is a shimmering swirl of “legends” drawn from stories ancient and new, sacred and profane, that comes into focus only in the imaginations of players, a tertiary concern compared to the premise of the game: the duel between two planeswalking wizards.

Knowing the allusions to ancient texts can enhance this atmosphere, and enrich the flavor of the fantasy of games of Magic as they play out. One might even venture (I’m thinking about it), that for early Magic, world-building was primarily about providing a usable and attractive user-interface for a rules system. One might further venture that for many people, religion functions much the same way.

Until next time.

Recommended Media

“Aziraphale and Crowley” from Good Omens

Song of the King from Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Coat

Parting of the Red Sea, from Prince of Egypt

“Why is Pork Forbidden?” By Religion for Breakfast

Price, M.D. Evolution of a Taboo: Pigs and People in the Ancient Near East. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

The Otherworldly Art of William Blake, by Eternalised

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.