Cover image: Chef’s Kiss by Iain McCaig

In an interview published in the art book Dark Souls Design Works, game director Hidetaka Miyazaki revealed that one of the more memorable bosses in Dark Souls was directly inspired by a specific character from the 1980s:

“There’s an old board game called Dragon Pass, one of my all-time favorites, and in that game is a unit known as the Cragspider. The game provides the name, parameters, and a tiny little chip with the silhouette of the creature. I’ll admit that’s not much to go on, but it was such a powerful unit and for some reason it really stimulated my imagination.”

Quelaag, the half-spider fire witch from 2011’s Dark Souls.

According to the concept artists working on Dark Souls, this sort of thing happened all the time—Miyazaki would bring them a board game piece, or a manga, or a “rumpled and stained book”, point to it, and say “Make it like this!” Here is the thumbnail-sized cardboard chit of Cragspider from the 1980 board game Dragon Pass that Miyazaki gave to his artists as the basis for Quelaag:

Given that Miyazaki was an avid Magic player (at least as of 2011), he may have done this with Magic cards too. Dark Souls hacker and modder @ZullieTheWitch has suggested that specific cards served as references for parts of Miyazaki’s other games like Bloodborne and Elden Ring.

In an interview, concept artist Daisuke Satake described a tendency of Miyazaki’s to reference old tabletop games for examples of imagery to explain to the artists. Imagine Miyazaki with a binder of Magic cards, pointing out specific card arts that had captivated him. pic.twitter.com/D0gXggNlvG

— Zullie (@ZullieTheWitch) May 4, 2022

In the comments on one of Zullie’s videos, Magic artist and Dark Souls fan Peter Mohrbacher is pretty sure that the design of at least one enemy from Dark Souls II was influenced by one of his Magic art pieces.

Grimgrin, Corpse-Born by Peter Mohrbacher.

The “artificial undead” as it appears in Dark Souls II.

Whether or not any of these are concrete connections or just coincidences, the idea of Miyazaki holding up specific Magic cards as reference pieces for his games emphasizes something that Magic and Elden Ring have in common: the way they use flavor text in storytelling.

See, games like Elden Ring and Dark Souls are a little infamous for their quirky approach to storytelling.

These games barely use the traditional techniques you’d see in games like Far Cry 6 or Horizon Forbidden West. Expositional dialog is extremely rare; cinematic cutscenes are reserved almost entirely for boss introductions, which tend to be more bewildering than explanatory. Instead, virtually all the story is “buried” in the flavor text of item descriptions.

For example, Dark Souls III includes an optional boss fight against a mysterious character who is strongly suggested by pieces of circumstantial lore to be a nameless figure that was previously only mentioned in the description of one single item from the first Dark Souls.

This gives you a fragmented view of the world: you get tons of little details, but few clear explanations of how they all fit together. Noone will explain to you exactly what the Dragon School of Vinheim is or what it has to do with the places you explore in Dark Souls, but you can meet this one dude who used to be from the Dragon School, and if you find his hat it’ll tell you that he didn’t like eye contact.

Inventory screen for “Big Hat” from Dark Souls.

Now, yes: It is, objectively, pretty funny that the way to piece together the sprawling capital-L Lore of Dark Souls is to collect people’s clothes and read their flavor text. But also, this approach to worldbuilding should be pretty familiar to fans of Magic, which has been doing essentially the same thing ever since 1993.

The original flavor text for Wall of Swords relays the twist ending of an epic tale of evil armies and cryptic prophecies centered on a character that, to the best of my knowledge, appears nowhere else in Magic lore. Justina’s prophecy, like Logan’s big hat, doesn’t help you understand the “main story” of Magic.

So why is it here?

Over the past three decades, Magic has tried all sorts of stuff to try to communicate the often complex plots that form the game’s canon, from books to video games to comics to web fiction to text on the bottom of the cards telling you what order to read them in (and telling you to go to a website for more info).

Sometimes this worked out pretty well. Most people knew that Emrakul got Imprisoned in the Moon at the conclusion of Eldritch Moon). Sometimes less so. Did you know that Kyodai, Soul of Kamigawa from Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty is That Which Was Taken from the original Champions of Kamigawa? Or that the reason why Konda, Lord of Eiganjo was able to steal it was because the barrier between the spirit realm and mortal realm on Kamigawa was weakened after Grandmother Sengir rang the Apocalypse Chime on Ulgrotha, which is where Homelands takes place?

One of the reasons for this ongoing struggle is that trading card games like Magic and open-world RPGs like Dark Souls are uniquely ill-suited for telling a linear story, because they have less control over the order that players experience the game components in. As Mark Rosewater, Magic’s head designer, put it:

“In most mediums, A will always happen before B, which will always happen before C, and so on. Trading card games don’t have that luxury. The first piece of the story you pull out of a booster pack might be N or V or F. The second piece could be before it or after it, and you don’t even know which direction it goes in.”

But while scattering lore across disconnected and disordered game pieces is terrible at relaying a linear story, it’s excellent for characterization.

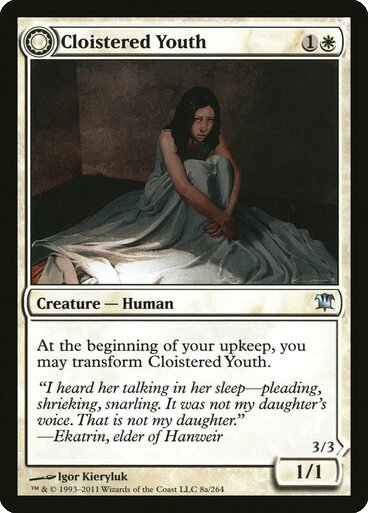

Here are three of my favorite examples from Innistrad: Stitcher’s Apprentice, Tribute to Hunger, and Cloistered Youth.

Each of these cards contains a vignette, told in a distinctive voice, about a named character that doesn’t appear in the official Innistrad story (which, at the time, was published in installments on Magic’s official website). These are isolated and disconnected stories, but they build a rich image of Innistrad.

In fact, scattershot flavor text can easily give you a deep and wide-ranging impression of people and settings exactly because it’s not constrained by linear narrative structure.

In a typical movie or book, the scene depicted in the flavor text of Rooftop Storm would need to be explained. (What’s Geralf doing? What are the stakes? How is it important to the story?) As an isolated piece of flavor text, however, the scene does the explaining (This is a world with blasphemous mad scientists, and Geralf is one of them!). In fact, Geralf and his sister Gisa are great examples of how you can convey potentially dense worldbuilding concepts like “the different types of necromancy and science on Innistrad” through character work—in this case, the rivalry between two adorably bratty siblings.

But flavor text is valuable for more than just telling us what is and is not a symbol of Avacyn’s church.

In a 2014 presentation at the Game Developers Conference, researcher Deborah Hendersen claimed that while players of video games often had trouble recounting the plot of their favorite games (compared to other media like movies or books), they had no problem recalling specific characters from those games. Other presenters at the conference agreed, arguing that “plot is overrated” compared to the characters that players will spend time with over the course of a game.

Flavor text lets you introduce tons of characters without overwhelming your audience. Instead of being a laundry list of names with varying importance for you to keep track of in order to make sense of a plot, the huge casts of nobodies and obscurities provided by flavor text make up a smorgasbord where you can pick out your favorites.

So when I say that Dark Souls III features a character who is only referenced in one piece of flavor text from a game that came out five years before it, that might make it seem like the lore of Dark Souls is impossibly arcane. But what if I told you that’s essentially the same thing that happened with this little guy?

The limited-edition plush of Fblthp, released by Wizards of the Coast.

At the time, Fblthp had only appeared in the art and flavor text of Totally Lost, but Wizards of the Coast released the limited-edition plush in resoponse to overwhelming demand from players. Mark Rosewater used this example in his own talk at a later Game Developers Conference to illustrate this lesson—“details are where players fall in love with your game”—but this sort of thing has happened numerous times before and after Fblthp.

One of my favorite examples is Braids, Cabal Minion. While Braids originated in the novelization of the Odyssey expansion by Vance Moore, she was a minor character that wasn’t intended to appear on any cards. Rei Nakazawa, who oversaw flavor text at the time, flagged the character as having a cool voice and personality. Magic designer Randy Buehler agreed, and was so captivated by the character that when the first piece of art that had been commissioned to appear on Diabolic Tutor came in, Randy instead repurposed it to give Braids her very own card.

I could easily double the length of this article with other examples, from Kynaios and Tiro of Meletis (who were invented after people wanted to know more about the story that appeared in the flavor text of Guardians of Meletis) to Asmoranomardicadaistinaculdacar (who originated in the flavor text of Granite Gargoyle, making her one of the oldest Magic characters). Hell, one of the other created-for-flavor-text characters I used as an example earlier in this article actually just got their own card in a Magic product that came out in the last few months—did you recognize them?

Despite its struggles in getting players to understand the canon storyline of each expansion, Magic has always kicked ass at creating evocative moments of characterization through its cards—and this has been the main way that players relate to the stories and worlds of the game. If you understand how people can fall in love with characters after meeting them incidentally through flavor text, you can understand why players who aren’t literature professors love poring over all the lore assembled by the incomplete puzzles throughout item descriptions in Dark Souls.

A world built out of disparate pieces of flavor text has room for so many more memorable details than you normally get in media that are ruled by stricter economies of narrative. That gives players a wider range of tastes to indulge, and lets them find the ones that they really bond with. At the end of the day, that matters more than whether or not players can give an accurate book report about your game’s plot.

Mani Cavalieri is a New York City-based writer, media critic, and your pale cousin who’s into reptiles. He publishes regular essays on media—from game reviews to gushing about how cool that weird Godzilla movie is —over on Eyez ‘n Teef (which you can also follow on Twitter, for all the trivia and toast recipes that don’t make it into full-length posts). He loves sharing cool things you didn’t know, and he WILL talk your ear off about them.