Cover image: Maestros’ Ascendancy by Jodie Muir

The doors of the train shut fast behind me as I descended the stairs from the platform to the bustling streets of the Windy City’s Uptown. The breeze off the lake was as chilly as the glares from passers-by on Broadway, and I was relieved to step into the warm, dim light of the Green Mill Jazz Club.

“Show’s not for a couple of hours. You’re early.” The bartender shot me a welcoming smile as she hastily wiped down the bar.

“I’ve got other business,” I smiled back.

I squinted as my eyes adjusted to the lamplight. It was dark, but my host was unmistakable. Tall, with long hair, Garneau had staked out a table in the back, to the side of the stage where we wouldn’t draw too much attention. His other guests had already arrived, two tough-looking guys I recognized from a chance run-in the day before.

Cabaretti Ascendancy by Olga Tereshenko.

“Thanks for waiting. Are you all ready?” I produced a small viridian box from my shoulder bag and placed it on the table.

“Ready. You already know about the Adversary?” Garneau’s eyebrows lifted quizzically as he produced his own box, black with detailing that defied my eyes in the gloom.

“I’m keen to see him in action,” I said. “I’ve heard good things.” The Adversary had become famous in the local scene. The pressure he put on competitors had a way of squeezing them until they made mistakes. Before they knew it, they had nothing left, and folded like the 1919 Sox.

“Let’s see what you brought, then.” Garneau produced a pair of dice from his pocket and let them tumble across the table. “Roll for first.”

And so my second game of Commander ever took place at the Green Mill, the historic speakeasy and once-favored nightspot of the Chicago Mob and the infamous Al Capone.

While I’ve taken liberties with the style, this story is true. My first game of Commander took place in my friend’s apartment, but my second game was at a table in the historical Green Mill Jazz Club. I was early for the show, and was back on the train before the music started, off to to grade papers and tuck children into bed, but I’ve long been enchanted by the romance of a city’s nightlife—of cocktails glistening in candle and lamp light, of streetlamps and glittering signs that inspire and provoke something like Thomas Merton’s urban epiphany in Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander:

“In the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all these people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world. . . . And if only everybody could realize this! But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun.”

Something about the power of light in darkness sparks a kind of joy deep within me; its ignition pulling the corners of my lips into a smile and filling me with the rush of possibility. Splendor. That’s the word for it.

Elspeth Resplendent by Anna Steinbauer

It was that same romantic mystique that prompted me, after finishing an art degree, to go to work as a bartender at a neighborhood martini bar in the Tower Grove East neighborhood of St. Louis. For years, I learned the art of charming guests and creating cocktails that could lighten and liven the atmosphere, stimulate conversation, and help music like the smooth jazz of Erin Bode Group or the soulful blues of the late Kim Massie elevate guests to near ecstatic bliss.

In the clubs of New Capenna, Kitt Kanto, Mayhem Diva, and Sizzling Soloist similarly sway crowds, pulling revelers from across the dance floor into a passionate whirl that cannot help but swing to the beat they lay down. “It makes no difference if it’s sweet or hot,” the song goes; “it don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.”

“Speakeasy Server” by Scott Murphy. I never could get my cocktails to float like this.

It was that same glamor of the music and lights that led me, for a brief time, to lean into nightlife as a career. On a moment’s notice, I dropped everything, and became manager of a new venue, which promised on its flyers to “redefine the art of dining and nightlife.”

The line of people dressed-up for a night on the town—old-hats, up-and-comers, and wannabes, exuberant with the possibilities the desire to put away all cares—was electric with aspiration. The shimmer of dance floor lights and the glint of cocktail glasses in red-curtained booths, the whirl of dancers and the raucous laughter, barely audible for the music, of friends and partners enjoying a night on the town, were enough to ensorcel us to believe in the vision, to keep the party going, night after night.

Gathering Throng by Randy Vargas.

The gathering throngs and their exuberance always felt familiar to me. For many, the venues became “church,” the bartender a confessor, the entire evening a ritual performed periodically, for some, daily, as a conduit of hope, or joy, or any number of spiritual aspirations. Which makes sense—what is more fundamental to human religion, to human existence, then coming together to break bread? To become literal “companions”?

Drawing on the traditions of ancient Judaism and European folk customs, my own religious tradition, Catholicism, peppered the year with feast upon feast celebrating everything from lofty and spiritual occasions of divine revelation to moments as quotidian as the dedication of a building. On every occasion, at least one chalice of wine is ceremonially raised, a cup that represents suffering, yes, but also catharsis and joy and salvation and being given over, “inebriated,” as one prayer puts it, by the spirit of the divine.

So it makes sense that the “party monsters” of New Capenna, the Cabaretti, were once a class of bards and druids, storytellers and singers and sages and priests, gathering the people together to hope for good times and to get through the bad.

As we tentatively venture back out in the shadow of a pandemic, cocktail lounges and concert halls again become secular spiritual sanctums, a reality I experienced again recently when a friend joined me to go to my first concert since 2019. We met at a restaurant on the same block as the Green Mill Jazz Club, the 1940s-decorated Fat Cat, catching up after months of conversations limited to group chats and brief texts. As the evening drifted toward night, the city lights ignited, transforming the world.

We left the neon lights of the Fat Cat behind us as we walked toward the Aragon Ballroom. The illuminated sign shone through the drizzly gloom, an oasis in the unseasonable chill of this year’s spring in Chicago.

The bouncers outside of the Aragon were businesslike and efficient. Identification, vaccine cards, metal detector, next. The foyer and long entry-hall of the grand ballroom was now a faded picture of its elegance as the center of late-20s dance hall culture in Chicago, but still more than impressive enough to make me pause to take in the grandeur. “They don’t build them like this anymore,” I thought… a sentiment I come back to for churches and concert halls alike.

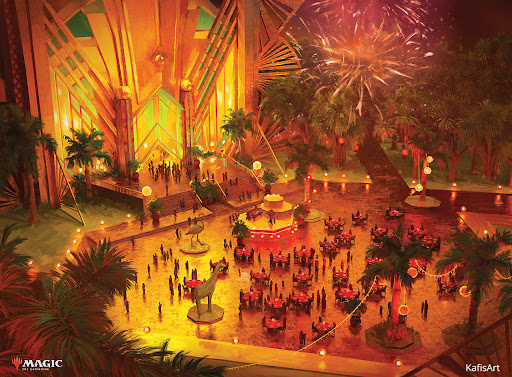

Cabaretti Courtyard, by Kasia ‘Kafis’ Zielińska. Not far off of the Aragon Ballroom.

The ballroom was almost as old as the Green Mill, and local legend was that the secret bootlegging tunnels from the jazz club led to a secret basement under the Aragon. I didn’t go looking. Instead, I stopped to marvel at the octagonal hall and its promenades, constructed to emulate the court of a Spanish castle, with the ceiling painted to resemble the night sky, complete with small, twinkling lights for stars.

The crowd filtered in slowly through the night, swelling with the music. As Tycho took the stage, fog and light drifted over the cloud, shrouding the space with an ethereal quality that transformed the soaring instrumentals and projected scenes of desert life into a refuge and aspiration. When they ceded the stage to Interpol, the positive atmosphere became pure electricity. The lights became brighter, the fog thicker, until the musicians were silhouettes amidst a luminous cloud. A Grand Crescendo. Shouts of elation, lyrics sung back from an impromptu, chaotic choir, hands raised in celebratory adoration, the gathered throng found its ecstasy under the painted skies of the Aragon ceiling, between the promenades and the balconies of its stylized interior.

Eventually, the band walks off; the bartenders yell “last call!” The bards and druids have filled the crowd with spirit and spirits, supplying catharsis and joy and hope as they always have, for thousands of years, and the crowd disperses. Tonight they slide into cabs or step onto the train.

I drive my way back to my flat in my neighborhood just north, where immigrants from Sweden moved to make a new life after the fire of 1871. Now it’s a diverse blend of peoples from all over the world, a kaleidoscope of humanity, still out and smiling, embracing, exhaling as the clock strikes midnight. The splendor of the sights, the sounds, the people will fade as the night wears on and the sun rises over the Great Lake, and nightlife transitions to the daily hustle and bustle.

What the splendor of nightlife shows us, of course, is at best a shadow of the real. It’s the favorable lighting of candles and streetlights, the best made-up versions of people out to wine and dine and dance and woo. The romance and the glitz is but a glimpse of something to aspire to, shaped and sold to us through showmanship. A glimpse, not untarnished by baser impulses. The revel, the feast, Eventually the lights come up, and the halo runs out.

Just like my own experience running a nightclub, what the Cabaretti do is tainted at least to some degree by greed and power and politics. The party is a masquerade, hiding their now-mythic origins as lorekeepers and soul tenders and mystics and naturalists. Again, from Thomas Merton’s Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander:

“There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun… If only they could all see themselves as they really are. If only we could see each other that way all the time. There would be no more war, no more hatred, no more cruelty, no more greed. . . . But this cannot be seen, only believed.”

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.