Hyperion by Dan Simmons (Bookshop.org | Amazon) is an underrated sci-fi classic.

Well, perhaps underrated isn’t quite the right word. Published in 1989, it went on to win both a Hugo and a Locus award in 1990 and is frequently well-reviewed on platforms like Goodreads, but it never broke into the zeitgeist like so many of its brethren have. In the age where Netflix and Amazon will adapt anything, it hasn’t seen any kind of release on either the small or silver screens, though Bradley Cooper has apparently been trying for a while.

Whether over-, under-, or properly rated, the fact is that Hyperion has stood the test of time. Set hundreds of years in a future when humankind has spread itself throughout the galaxy, it follows seven strangers that have been chosen to make the final pilgrimage to meet the mythical Shrike on the backwater world of Hyperion. The story is structured in a way that each pilgrim gets the chance to tell their tale over the course of the journey, resulting in a book that feels more like several novellas with their own points of view and narrative styles, separated by brief interstitial set in the book’s present to keep pushing the journey towards its ultimate destination.

“The Great Grass Sea” by Sabin Boykinov

In order for you to reach that destination, dear reader, it’s important to understand that Hyperion ends after 500 pages on a cliffhanger—a jarring and absurd one, in my opinion. So, if you want a complete story, you’re actually committing yourself to read a second 500-page book as well.

Yes, a total of 1,000 pages is required to bring Hyperion’s story to a close. I was blissfully unaware of this fact when I began the book, and I didn’t plan on reading any of the three remaining books in the Hyperion Cantos (The Fall of Hyperion, Endymion, and The Rise of Endymion). But I still wanted more stories in Hyperion’s setting even after the lengthy tales of the seven pilgrims.

Much of my willingness to continue was due to the fact that Hyperion’s universe is a vibrant extrapolation of what human society could look like if everything was digitized and every person had nearly instant access to any piece of information. (Remember that the internet was in its infancy when Simmons published Hyperion—14 years before Snow Crash and 22 before Ready Player One, for reference.) At the dawn of the computer age, Simmons saw very clearly the double edged nature of the coming advances. His vision of such a future shows both the promise of amazing technology and how it can rot away some of what makes us human.

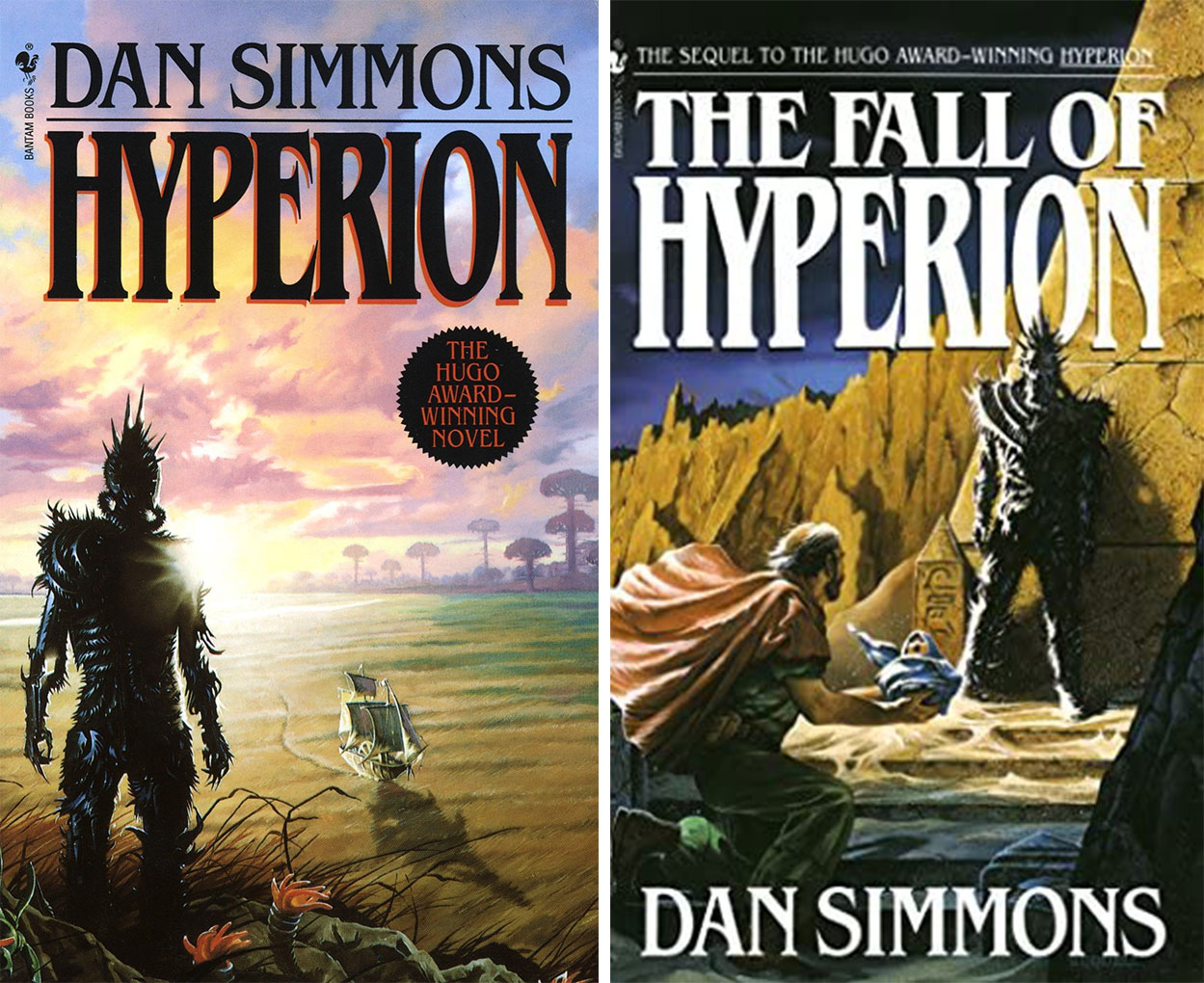

Admittedly, the 80’s techno jargon—the “All Thing,” the “TechnoCore,” “cyberpukes,” etc—feels a bit dated, but I find it charming more often than not. The same can’t be said for the book’s cover art, whose style apes that of many other classic sci-fi books but fails to evoke the same kind nostalgia for me. (And check out the art for The Fall of Hyperion, which veers so far into cheese that it looks like a parody of a Bible cartoon.) Honestly, I opted for a more modern paperback cover whose art represents the stories of the seven pilgrims weaving together.

Hyperion’s story is very much built as a space opera, focusing on the seven pilgrims and their unique reasons for making the journey while the galactic world order teeters on the verge of war. And Simmons reveals an extremely engaging mystery right at the outset: one of the pilgrims is an enemy spy. The political and military dramas only escalate in the second half of the story, The Fall of Hyperion, as Simmons widens his focus beyond the pilgrims to spend more time with the rest of humanity and the fallout from the start of war.

Many of the themes the books explore are similarly operatic. Both Hyperion and The Fall of Hyperion are preoccupied with the 19th Century English poet John Keats, particularly with the poet’s abandoned works titled Hyperion and The Fall of Hyperion. (Sound familiar?) The capital city of the planet named Hyperion is called Keats, one of the pilgrims is a poet, and on and on. You by no means need any preexisting knowledge of Keats to understand Simmons’s work—he gives you more than enough context as the books progress—but some familiarity will add an enjoyable level of depth to the experience. Both writers were interested in exploring the tragedy and turmoil caused when old gods are usurped by new gods, though Keats staged his story in the ancient past while Simmons set his far in the future.

I’m still not sure why it took so long for Hyperion to find its way onto my “Want to Read” list, but it quickly made its way on to my “Read it Again” list as soon as I finished reading. It’s worth your time and deserves a spot on your bookshelf.

Rating: ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ for Hyperion—buy a hardcover copy and revisit it. (Though they’re really expensive, so you should go with a paperback instead. I infinitely prefer this paperback’s cover, anyway.) ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ for The Fall of Hyperion.

You can buy Hyperion Bookshop.org or Amazon.

This post contains affiliate links from which Hipsters of the Coast may make a small commission.