Over the past few years, Wizards of the Coast has increased Magic’s complexity. This was an intentional choice with the goal of making Magic (especially Limited) more fun and dynamic. We’ve seen this change expressed in several increases, from the amount of text on cards to the number of keyword mechanics and use of unnamed mechanics. Wizards knows that such moves require caution—Time Spiral and Lorwyn blocks alienated prospective players with their high levels of complexity in card text boxes and type lines, respectively.

Fortunately, Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty seems to thread this needle. So today, let’s examine what challenges Neon Dynasty presented, how Wizards managed its increased complexity, and areas likely to trip players up.

Cycling through myriad options

Channel is arguably the most challenging keyword mechanic in Neon Dynasty. Sure, Ninjutsu requires players to understand the phases of combat, demands a lot of player communication, and makes interacting during Declare Blockers are challenging proposition; but it always has the same inputs (spending mana and returning an unblocked attacking creature to hand) and outputs (placing a ninja onto the battlefield in its place).

Channel is a simple mechanic on its face—it’s like Cycling or Split Cards. However, it has highly varied outputs, where every card generates a different spell effect. This can create memory issues, where too many cards have too much text to keep track of and present an overwhelming number of options. Magic mitigates these memory issues by having Channel effects relate to the card’s normal effect—sometimes.

Some effects are perfectly aligned, as with Twinshot Sniper (where Channel is effectively Evoke). Sometimes, there’s an indirect connection (Mirrorshell Crab‘s Ward 3 and Mana Leak that also Stifles so it can counter Channel) or a mechanical link (Roaring Earth converts mana into +1/+1 counters when drawn early or late). Sometimes, there is no connection, but the card is vanilla (Eigango, Seat of the Empire). But sometimes, the effects misalign (Ironhood Boar provides a stat bonus unrelated to its stats and only half of its keywords) or have no relation whatsoever (Moonsnare Prototype and Sunblade Samurai). Some Channel effects are easier to learn and remember than others, and another way Wizards kept Channel in check is by only putting 23 in the set (including a five land cycle).

A second issue inherent to Channel is that it functions at instant speed. Magic plays better when the majority of games don’t involve mana primarily being spent mana on opponents’ end steps—in such a world, there’s little room for things like blocking, combat tricks, or sometimes, playing creatures. In addition, sets can be overwhelming if there are too many instants to keep track of. Wizards addressed this by both keeping the number of instants low and designing Channel effects that mostly didn’t support draw-go Magic.

Ultimately, two factors work overtime to make Channel work well. First, Channel is hidden in the hand. It doesn’t present onboard complexity because only one player knows its there (most of the time). Sure, more enfranchised players might furrow their brows trying to play around Channel, and players might not know the right times to Channel or cast their cards, but it won’t make the battlefield any harder to understand. But less enfranchised players won’t even know what to worry about, and so won’t have to deal with the complexity it adds.

Second, Channel is discrete—once it’s done, it’s done. Channeling is a singular decision that has a singular spell effect on the game state, and then the game continues. Sure, the outputs vary widely, but the effect is immediate and then ends. All of that helps to make Channel lenticular (where the complexity and power it presents is often hidden from players who might by overwhelmed by it) where a different execution of Channel could have been omnipresent and overwhelming.

How Sagas help

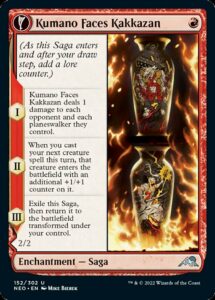

Sagas are inherently complicated cards, since they provide multiple effects and each has unique outputs (just like Channel). Neon Dynasty’s sagas are especially complicated—their text is spread across two faces of a card, so you can’t read all of it at once. Now, you’re not only planning how to maximize spell effects, you’re always planning around creatures with Suspend 2 (without Haste). However, sagas are inherently fantastic at throttling their complexity because they involve no choices. They trigger once per turn and all you need to do is remember to perform that trigger (and in digital Magic, this is all done for you).

Moreover, every saga functions the same, so once you know how to execute one saga, you know how all of them work. It’s an easy heuristic to build. Sure, each saga’s outputs are unique, but when the inputs and execution are the same, they become much easier to play with.

When the set was first previewed, I was concerned that having common and uncommon sagas with comparable amounts of text to Strixhaven’s Deans could be a recipe for disaster. But this fear proved utterly unfounded. Strixhaven’s Modal Double-Faced cards required you to deeply appreciate two halves of a card (that you couldn’t see at the same time) before committing to the choice of which side to play. Neon Dynasty’s sagas merely ask you to play them and then they do the rest, which is an even simpler decision than whether to Channel.

So much of these sagas’ complexity happens as a result of strategic play—deciding the optimal time to deploy them, finding opportunities to reuse them with Ninjutsu, Geothermal Kami, and Season of Renewal, and identifying all the synergies they provided. But this, again, is lenticular: complexity invisible to the people most likely to be discouraged by complexity.

Optimization and inconsistency

On a big picture level, I’m incredibly impressed by Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty. It manages to balance feature mechanics that could easily go awry alongside a variety of strategies and unnamed mechanics. Sure, there’s a lot going on between Ninjutsu’s combat heuristics, Reconfigure’s additional decisions as compared to Equipment, and everything we’ve mentioned, but so much is sectioned into specific timings or play patterns that it ends up feeling coherent and consistent rather than a chaotic collection.

That said, I’ve not found it to be completely smooth sailing even after a few weeks. The issues I’ve had along the way are small, but they’re suggestive of potential pitfalls down the road if they become more present. Magic can optimize for a variety of things, and Kamigawa has bits of optimization for power that can sometimes come at the expense of being optimized for ease of use.

Sunblade Samurai has one of the most missed triggers I’ve seen when playing in paper. The addition of 2 life is a nice way to squeeze in some extra value and further distinguish it from Plainscycling. However, because the lifegain is almost always a bonus effect to the primary goal of grabbing a land (and has nothing to do with anything on the card), it’s easy to forget about. This demonstrates one potential danger of optimizing for secondary effects: when cards do too many things at once, especially when there’s no clear thematic or mechanical connection, they get harder to remember and play correctly.

We’ve already discussed Moon-Circuit Hacker at length, and it has a similar issue. Sunblade Samurai has a forgettable secondary effect, while Moon-Circuit Hacker has a subtle secondary function—being an enchantment. This allows it to support Neon Dynasty’s enchantment and harmony subthemes while fulfilling its primary role of being an awesome ninja, but this functionality is obscured by being utterly unrelated to how the ninja deck and Ninjutsu mechanic function. Furthermore, it relies heavily on the card border to communicate that it’s an enchantment, a marker not present on the showcase version. This would be a bigger issue if the format had a mechanic that cared about quantity of enchantments (Constellation, for example) rather than their mere presence, or if there were more enchantment removal. However, this seems like something to keep watch for—one of Lorwyn’s most fatal flaws was compressing too much vital information into card’s type lines.

Finally, let’s discuss the problem of inconsistency. When similar cards behave differently, designers set players up to make mistakes. Michiko’s Reign of Truth functions the way that most cards do—when the ability resolves, it checks the state of the battlefield to determine its effect. So do Banishing Slash, When We Were Young, Heir of the Ancient Fang, and Kami of Terrible Secrets. However, cards like Soul Transfer, Flame Discharge, and Assassin’s Ink can’t work that way as they need to lock in information about the battlefield as soon as they’re put onto the stack. Those cards are fine—they function a bit differently out of necessity, but shouldn’t pose too much of a comprehension issue.

The issue arises when cards that don’t have to be exceptions to the rule are. You can disable the card draw from Ambitious Assault or damage from Kami’s Flare by killing your opponent’s last modified creature, you can reduce the damage caused by Thunder Raiju the same way, but Lethal Exploit locks in its effect at the time of casting. There are good reasons to create this exception (the card is a bit more powerful, the other cards use Modified to get a bonus effect while Lethal Exploit scales its primary effect, you eliminate an undesirable play pattern when a removal spell is itself vulnerable to removal), but exceptions breed mistakes, except when higher complexity leads to more things to remember.

When Neon Dynasty was announced, I was fully prepared to dislike it. I had no nostalgia for the world, its mechanics (save Ninjutsu), or cyberpunk. When spoiler season began, I was more than a little bit concerned at how much it had going on (especially in the wake of two Innistrad sets with six keyword mechanics). And yet, somehow, Wizards pulled off the impossible and created that continually impresses with all the painstaking effort that went into it.

Sure, there are a couple of pain points that may be repeated in future sets, but there is no such thing as a perfect Magic set—the flux of the game is central to why it’s as amazing as it is, so there will always by oscillations from experimentation. And for me, the opportunity to witness and learn from this constant work ranks among my favorite parts of Magic.

Zachary Barash is a New York City-based game designer and the commissioner of Team Draft League. He designs for Kingdom Death: Monster, has a Game Design MFA from the NYU Game Center, and does freelance game design. When the stars align, he streams Magic (but the stars align way less often than he’d like).