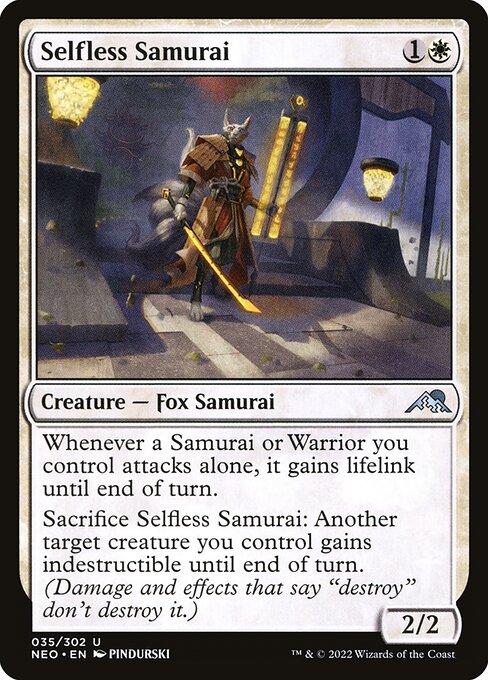

Cover image: Selfless Samurai by Hugh Pindur

I grew up making regular trips to the “Red Fox,” a friendly grocery store in my small village on the Illinois prairie. Combined with Disney’s depiction of Robin Hood as a crafty red fox who fought for social justice, my experiences at the Red Fox, with its grinning mascot and kind owner, cemented foxes as one of my (admittedly plentiful) favorite animals. Thus, when I opened booster packs of Throne of Eldraine a year after returning to Magic, and saw foxes featuring prominently in the art of eight cards, I was elated. When Ikoria followed it, a few months later, with five more foxes, I began to speculate that someone at Wizards must also admire these clever creatures.

The Red Fox logo.

Longtime readers will guess that I also began to think about the archetypal characteristics and meaning of foxes in folklore as it inspires Magic: the Gathering, as well. The article that I wrote then about Ikoria left aside any consideration of vulpine veridities, but with a return to Kamigawa and its kitsune imminent, the question of the fox and its meaning has come again to my mind. In other words, when we’re talking about ancient folklore, spirituality, or even contemporary fantasy narratives, “What does the fox say?”

Among other things, in this article, I contend that the fox, as an archetype, holds in tension a number of dualities that make it an exemplar of indigenous Japanese thought (in part because it has been given this role in Japanese folklore and religious thought). The fox is both trickster and guide, elusive loner and the healer of communities. While not a focus of the set or its story, the dualities of the kitsune augment Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty’s overarching aesthetic contrast of tradition vs. modernity to subtly lend the worldbuilding more of the cultural character it needs to be received as a respectable portrayal of a fantasy world so clearly based on a real world culture.

The Trickster and the Guide

Owing to its reputation for sneaking into hen houses and then eluding hunters, ancient stories about the fox, such as Aesop’s fables, have often depicted the fox as a mischievous trickster, giving rise to a number of idioms referring to the animal’s cunning or elusiveness such as “outfox,” and perhaps even Shenanigans (from Irish sionnachuighim, “I play the fox”).

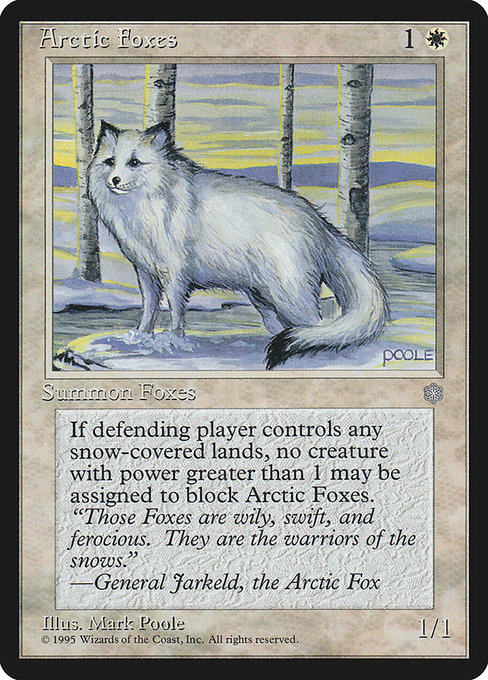

We see the fox’s cunning and evasiveness exemplified in Magic from the very first fox printed, Ice Age’s Arctic Foxes. The otherwise underwhelming white two-drop nevertheless earned high praise for being “wily, swift, and ferocious… warriors of the snows,” as noted in the flavor text from General Jarkeld, himself dubbed “the Arctic Fox.” Foxes are also referenced in the art and the cardname of a combat trick from the same set, Foxfire. A similar effect can be seen on Alliances’ Undergrowth, which features a hiding fox, again leaning into foxes’ folkloric reputation as evasive and cunning creatures. This trend continues in Magic’s foxes in later sets, reaching its apex, perhaps, on Eldraine’s “craftier-than-a-dragon” Flutterfox.

The duality of the fox comes into play when we consider that while cunning and mischief are often coupled, the mature side of cunning is wisdom. In some stories, the fox is a guide, or messenger of the divine, offering counsel to the hero. We see a relatively recent example of this in Antoine Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince (1943), in which the fox tells the prince, “I shall tell you my secret. It is very simple: One sees clearly only with the heart; what is essential is invisible to the eyes.” The fox directs the prince to the true nature of things, advising him to look deeper than mere appearances for true meaning and happiness.

While they don’t have words of wisdom per se, Shadows Over Innistrad’s Devilthorn Fox and Ikoria’s Farfinder are implied to be acting as guides to safety. For true wisdom, however, we must turn to the kitsune of the Kamigawa block.

Tails of Wisdom

The original Kamigawa block most firmly establishes the “fox” creature type’s identity in Magic. Its seventeen kitsune are largely united as a tribe of white foxes mechanically focused on damage prevention. Kamigawa’s kitsunes are also visually unified, having white or light gray fur, and red markings, inspired by the symbolic depiction of foxes in Japanese statues and masks, often found at shrines of Inari, the kami of prosperity.

Footage from a festival at Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto, showing Inari masks.

As in Japanese folklore, Kamigawa’s kitsune grow additional tails as they grow in age and wisdom, with extremely wise elders achieving a full nine tails. In folklore, kitsune with multiple tails are said to possess great mystical power, and nine-tailed foxes allegedly ascend into heaven, becoming celestial beings. In Magic lore, Eight-and-a-Half Tails was once Nine Tails, but as self-imposed penance for being tricked into helping Emperor Kondo, removed the tip of one of his tails. Light-Paws, Emperor’s Voice, who mentored Kaito and Eiko, is similarly a multi-tailed kitsune.

Light-Paws, Emperor’s Voice by Randy Vargas

The role the kitsune plays in Shinto spirituality—one evoked by Kamigawa’s kitsune’s iconic appearance—is the locus of its other duality that I wish to point to here: the kitsune is a symbol of the tension and the border between the individual and the community, between personal expression and the importance of the whole. And nowhere is this seen more clearly than in Inari worship.

Inari has been worshiped for over 1,300 years in various forms—their gender is fluid from depiction to depiction, as is their patronage. Where agriculture, particularly rice farming, was once their principle domain, they have been appropriated across professions and even across religions, showing up in Buddhism as an androgynous, fox-riding Boddhisatva. Whatever a person needs Inari to be, Inari becomes that for them. As one Shinto priest put it, “If there are one hundred believers, they will have a hundred different ideas about Inari.”

“Blacksmith Munechika, helped by a fox spirit, forging the blade Ko-Gitsune Maru” by Ogata Gekkō (late 19th-early 20th Century).

Anthropologist Karen Ann Smyers writes that “Inari worship is the form of religion in Japan that seems to contain the most personalization,” which is fitting, as the most common symbol for Inari is the fox—a solitary animal associated with individualism. Where mystical foxes are encountered in Japanese stories (being possessed, tricked, or even seduced by a kitsune, or receiving healing or a gift from one), it is almost always a one-on-one encounter.

In a 1996 article in The Japanese Journal of Religion entitled, “‘My Own Inari’: Personalization of the Deity in Inari Worship,” Smyers goes on to say that in Japan (at least Japan of the late 1990s), the pressure of social conformity renders obviously individualistic behavior liminal—that is, on the “boundary” between worlds—and that same mode of being “betwixt-and-between” characterizes the religious significance of Inari and her foxes in Shinto. In a subsequent article, Smyers notes that in a country “where social expectations are for group cohesiveness and harmonious cooperation at the expense of individual desires, the liminal release” of Inari worship bucks typical expectations of religious pilgrimages (which more often emphasize community and belonging), allowing passage into a place of the expression of “particular individual needs and desire.”

Thus does the symbol have its two valences: the kitsune is both wily trickster and wise healer, both a loner and a stalwart protector of their community. Smyers tells of how many people are brought to the mountain of Inari to be helped navigate their problems and return to their place in society. Through prayer and care by the “clergy” there, pilgrims are able to receive personal guidance, and return to a place of balance. Smyers argues that in this model of care, we see that the personalization of the Inari deity and their rituals “does not promote wanton individualism, but is in fact a way to acknowledge personal or individual concerns, deal with them, and thereby learn to function in a society that does not give them much formal recognition.”

Kitsune: from the world-building guide.

A Fox Offering

Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty’s kitsune bring this forward in much the way that dualities often present themselves: in subtle harmony. While previous iterations of kitsune did this through combining “trickery” and “healing” with instant speed damage prevention, Neon Dynasty’s kitsune emphasize these the archetypal dyads: wily and wise, individual and communal, in a variety of ways. Selfless Samurai, for example, makes itself or another samurai or warrior more potent when it attacks alone, but can also give itself up to protect another.

Light-Paws, Emperor’s Voice can be read similarly. Her aura-seeking ability triggers in response to her controller casting an aura, no matter which creature one targets, but then attaches the found aura to herself. Strengthening her comrades strengthens her. Seven-Tail Mentor likewise serves as a kind of guide, training up their allies in their comings and goings.

Where Neon Dynasty’s kitsune seem to deviate in mechanical identity, they harken back to the fox as a formidable and crafty figure. For example, Blade-Blizzard Kitsune can utilize ninjutsu to slip onto the battlefield undetected, its blades whirling across our opponent’s life total. Kitsune Ace and Hotshot Mechanic apply their cleverness to vehicles, but also point us to the relationship of the individual with the communal through its allusion to familiar characters: the “fox pilots” remind us of Fox McCloud from Nintendo’s Star Fox and Miles “Tails” Prower, from Sega’s Sonic the Hedgehog, respectively: heroes that have their friends’ backs as they fight together against evil.

The kitsune of Kamigawa have in some sense always been a place where the influence of the folklore and spirituality of Shinto and Japanese Buddhisms could be felt organically; Neon Dynasty continues this trend. As the curtain closes on Neon Dynasty’s story arc, and The Wandering Emperor passes her authority to Light-Paws, the people of Kamigawa are left, like those pilgrims to Fushimi Inari-taisha (伏見稲荷大社), to trust in the fox to guide them to prosperity and harmony with those around them, and to navigate a world that is, like ours, struggling with the balance between tradition and modernity, between the personal and the political, between spirituality and technology.

Until next time.

⛩

If you like to immerse yourself in music while streaming, playing, or thinking about Magic: the Gathering, I’ve made a playlist following the themes of this article. You can enjoy it here:

⛩

Resources & Recommended Media

Smyers, K.A. “‘My Own Inari’: Personalization of the Deity in Inari Worship,” in The Japanese Journal of Religious Studies Vol. 23, No. 1/2 (Spring, 1996), pp. 85-116. Nanzan University.

Smyers, K.A. “Inari Pilgrimage: Following One’s Path on the Mountain” In The Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, Volume 24, No. 3 / 4, Pilgrimage in Japan (Fall 1997): 457-452.

Nakazawa, Rei, “The Story of Eight and a Half Tails”.

Bowman, Akemi Dawn, “Kaito Origin Stories: A Test of Loyalty & The Path Forward”.

Rhystic Studies, “The Old Kamigawa”.

Gregory, Kristen E., “Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty Is Basically The First Universes Beyond Set”.

Carter, Chase, “Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty avoids cyberpunk-shaped pitfalls and the ghost of its predecessor”.

Bhatt, Shivam, “Thread on Roadside Reliquary and Japanese Spirituality”.

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.