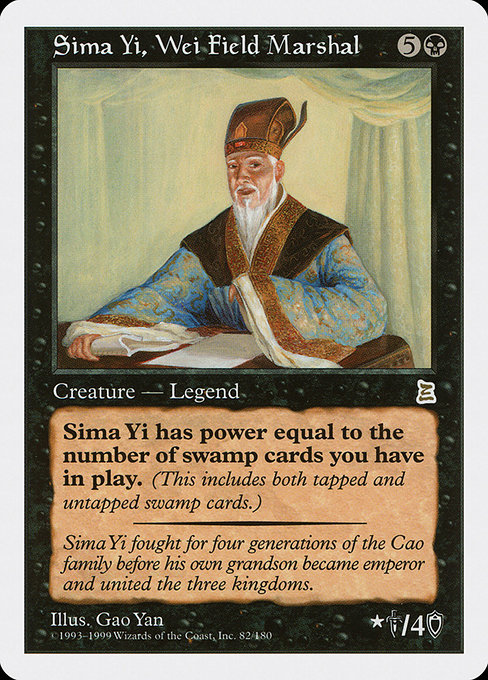

Cover image: Sima Yi, Wei Field Marshall by Gao Yan

In this conclusion to my P3K summary series, I move from summary to commentary. My commentary here is indebted to Moss Roberts, the translator of the edition of the novel used in the design of the set, and to CJ Leung, of the Cool History Bros Youtube channel,whose own commentary and video summary of the novel I highly recommend.

Read our interview with set designer Henry Stern and the earlier entries: Introduction; The Yellow Scarves Rebellion; Dong Zhuo Takes Control; The Dying Embers of Rebellion; The Rise of Cao Cao; Cao Cao Conquers the North; The Battle of Red Cliffs; How the West was Won; The Fall of Guan Yu; New Emperors

Sleeping Dragon’s Fire Goes Out (228-234 CE)

Zhuge Liang, known as Kongming, Sleeping Dragon—despite his legendary skill as a strategist, he found his ambitions stymied by poor personnel and growing decadence and corruption in the Second Emperor’s court at Chengdu, the Shu capital. His series of five expeditions against Cao Wei succeeded in defeating the Wei army on a number of occasions, but a lack of food and personnel prevented him from capitalizing on his victories, eventually forcing the Shu troops to retreat to secure more resources.

Sima Yi ordered Zhang He to pursue them, but overconfidence on Sima Yi’s part pushed Wei forces straight into a Shu ambush, where Zhang He met his end after he took an arrow in the knee.

In the coming years, Kongming took measures to mitigate his logistical challenges. After two years of preparation, the Sleeping Dragon launched his last expedition. However, the stress of war and overwork had taken their toll on Kongming, and he fell seriously ill and died in camp at only 53 years old.

Sima Yi, hearing that the Shu army was retreating, deduced that Kongming had died, and quickly pursued. He was met by the rearguard, however, who feigned a counterattack, casting doubt into Sima Yi’s mind as to whether Kongming was actually dead. The Wei army halted their pursuit, allowing the Shu army to escape. This one last deception gave rise to the popular saying, “A dead Zhuge (Liang) scared away a living Zhongda.” Sima Yi replied: “I can handle the living but not the dead.”

The Kingdoms’ Virtues Turn to Vice (234-280 CE)

With Kongming dead, of the original heroes, only Sun Quan and Sima Yi remained. Sima Yi continued to advance in power, conquering Shu-Han and gathering authority to himself until he was able to oust the Wei emperor’s regent from power in a coup d’etat in 249. Sima Yi died in 251, but his coup paved the way for his grandson, Sima Yan, to depose the Wei emperor in 265, and become the first emperor of the Jin Dynasty.

Sun Quan ruled Wu as Emperor until his death in 252, after which controversies over succession led to the decline of the Sun family’s power and reputation. Sun Hao, the fourth and final emperor of Wu, was defeated by Sima Yan’s armies in 279.

The last fifteen chapters of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms are rarely included in summaries. Portal Three Kingdoms follows this trend: it bears almost no trace of the aftermath of the main characters’ deaths and the subsequent reunification of the empire under the Jin Dynasty, save a brief allusion in the flavor text for Sima Yi, Wei Field Marshal, and the flavor text on nine of twelve cards in the the zodiac cycle. This is due, in part, to it being a story of failure. By comparison to the previous generations, the characters of the final chapters are weak and unheroic, preoccupied with decadence or stymied by court corruption.

In short, after the deaths of their founders, the virtues of the Wu, Wei, and Shu kingdoms turned quickly to vices. Wu, which had been focused on the Sun family legacy, became weak due to nepotism and a succession crisis that led to infighting. By contrast, Cao Cao’s kingdom of Wei, which looked less to lineage and more to an individual’s merit, became a culture of back-stabbing fueled by self-interest; ultimately usurped by the Sima family, just as Cao Cao had usurped the Han emperor.

Where Shu had been founded on loyalty to the Han and loyalty between Liu Bei, Zhang Fei, and Guan Yu; its fall was facilitated by blind loyalty to poor leaders, and the same kinds of court corruption that brought down the Han empire decades earlier.

Aftermath: Ravages of War

The reunification of China under the Jin Dynasty was not a restoration to the glory of the Han. At its peak, the Empire under the Han Dynasty had a population over 56 million. A series of natural disasters, such as an earthquake and devastating tsunami, the Yellow Scarves Rebellion, and decades of conflict between feuding warlords brought waves of plague and frequent famines that were reported by multiple sources to have driven some to cannibalism.

Additionally, the historical Cao Cao was more ruthless than his literary counterpart, massacring civilians and prisoners of war, on some occasions tens of thousands at a time. The historical Liu Bei, also more cunning and ambitious than his fictional counterpart, was nevertheless easily seen by commonfolk as heroic by comparison, because he didn’t massacre entire towns. Between war casualties, famine, plague, and refugees fleeing these conditions, the population of China fell by over 70%—from 56 million to 16 million—in a single century.

The Three Kingdoms as Literature

As one might expect, the nearly 100 years of violence left an impression on those who remained. Romance of the Three Kingdoms as we know it today is the collection of folktales and official histories that retell the story of this devastating period of civil war. The continuing retelling brought ever more changes to the way the story is told. Nearly 1000 years later, in the Song Dynasty, these stories had begun to characterize Cao Cao—initially framed in official histories as a legitimate ruler—as villainous, and Liu Bei as an exemplar of Confucian virtue, in part because these characteristics served the interests of the ruling dynasty. Shortly after the fall of the Song Dynasty to the Mongols, the folk stories began to see publication in both written and theatrical form, adding more supernatural and fictionalized events.

In the time of the Ming Dynasty, it’s thought that Luo Guanzhong took from all of these materials to create the version that would later be edited by a father and son, Mao Lun and Mao Zonggang, into the version that I’ve summarized over the past few months, which is the inspiration for Portal Three Kingdoms. As CJ Leung comments at Cool History Bros, the synthesis attributed to Luo puts the political and philosophical questions of both the peasantry and the ruling class on display, and invites the reader to think about these questions along with them: “Liu Bei was benevolent and righteous, but Cao Cao wasn’t without merit . . . Is righteousness worth anything if you don’t have the power to uphold it?” Similarly the Sun family, ruling Wu, are in the midst of a Confucian dilemma: if the empire falls to Wei or Shu, the victor will surely come after them. Which is more important, loyalty to country, or loyalty to family?

The editors added the famous line, “The empire, long united, must divide; long divided, must unite” to the beginning and ending of the novel, placing it within a cyclical notion of time that explains the rise and fall of dynasties. They also strengthened the narrative structure by subtly shifting the depiction of how battles are won throughout the novel. In the beginning, battles are won through martial prowess and heroism. Later, the focus moves to strategy. As our heroes become generals and kings, the novel focuses more on their skill in delegation, and as they become emperors with their own children, we see the difficulty of establishing succession and raising the next generation to carry on the work.

The abundance of meaning in Romance of the Three Kingdoms is part of why it is a true classic, and one of the “Four Great Novels of China.” It continues to be a living narrative, with new iterations and retellings constantly being published as novels, video games, films, and comics, and yes, card games—each with different emphases, finding new ways to ask ancient questions, and new ways for its audience to relate to old heroes.

Epilogue: For all to ponder

As with many summaries, Portal Three Kingdoms omits almost all of the final fifteen chapters of the Romance. Designer Henry Stern did preserve the novel’s epigraph in the flavor text of the “Zodiac” cycle, however. I’ve put the entire poem here in these galleries, with the cycle of creatures in their appropriate places. The Chinese zodiac is a repeating cycle of twelve years. Stern’s use of the zodiac in this place is either a happy accident or incredibly insightful: the placement of the zodiac animals here evokes universal meaning of the Three Kingdoms, summed up elegantly in the cyclical nature of the maxim that begins the novel: “The empire, long united, must divide; long divided, must unite. Thus it has ever been.”

So ends our tale. It is my sincere hope that you have found this retelling of the Three Kingdoms story, which places the Portal Three Kingdoms cards in their narrative contexts, to be enjoyable and edifying. Until next time.

Recommended Media

Luo Guanzhong, Three Kingdoms (trans. Roberts, 1991), Ch. 98-120 (pp. 745-end).

Zhang Qirong & Li Chengli, Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Asiapac Comic Series: 1995/2006), Vol. 9-10.

Cool History Bros, Romance of the Three Kingdoms – EP6: Zhuge Liang vs. Sima Yi.

Cool History Bros, Romance of the Three Kingdoms – EP7: The End of the Three Kingdoms.

Cool History Bros, Why You Should Read Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.