Cover image: Red Cliffs Armada by Zhang Jiazhen

Read our other entries: Introduction; The Yellow Scarves Rebellion; Dong Zhuo Takes Control; The Dying Embers of Rebellion; The Rise of Cao Cao; Cao Cao Conquers the North

Liu Bei on the Run (201 CE)

Now that Cao Cao controlled the North, Liu Bei was again left without a home. Together with his oathbrothers and Zhao Yun (Zilong), Liu Bei was forced to flee from Runan and took shelter with Liu Biao, governor of Jingzhou. However, Lady Cai, mother of Liu Biao’s youngest son, heard Liu Bei advising his host not to name her son as heir ahead of the elder son. She began to conspire to have Liu Bei eliminated.

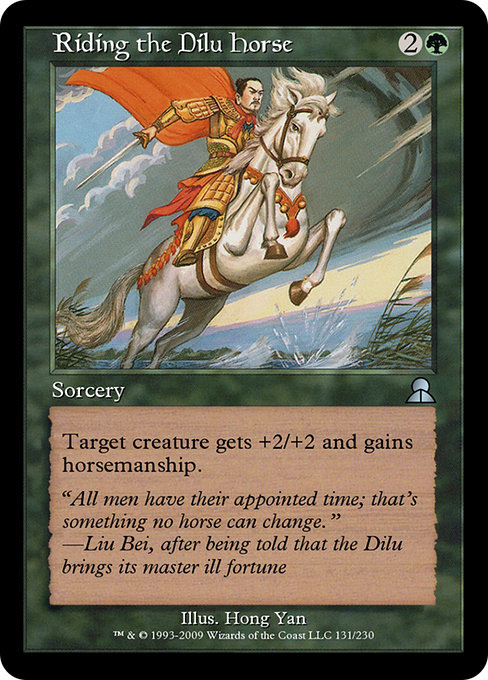

During this time, Liu Bei was successful protecting the province and became popular with the people. After one battle with bandits, he acquired the Dilu horse, sometimes translated “Hexmark.” The horse was so-named because of the white spot on its head, which was said to indicate that it would bring doom to its rider. Liu Bei, never one for superstition, was unbothered by this.

Despite Liu Biao’s respect for Liu Bei, Lady Cai and some of Liu Biao’s advisors plotted to kill Liu Bei at Xiangyang, formally requesting his presence. Suspecting a trap, Liu Bei took Zhao Zilong and 300 soldiers with him. Despite their preparedness, Liu Bei nevertheless found himself isolated at a banquet, only escaping when he was warned by a trusted advisor.

Fleeing west on the Dilu Horse, Liu Bei found himself trapped by the river. As he attempted to cross, his horse lost its footing and began to sink. “Hexmark! Will you be the end of me?!” Liu Bei cried—and as if by a miracle, the horse vaulted across the rapids to safety on the opposite bank.

Enter the Dragon (207-208 CE)

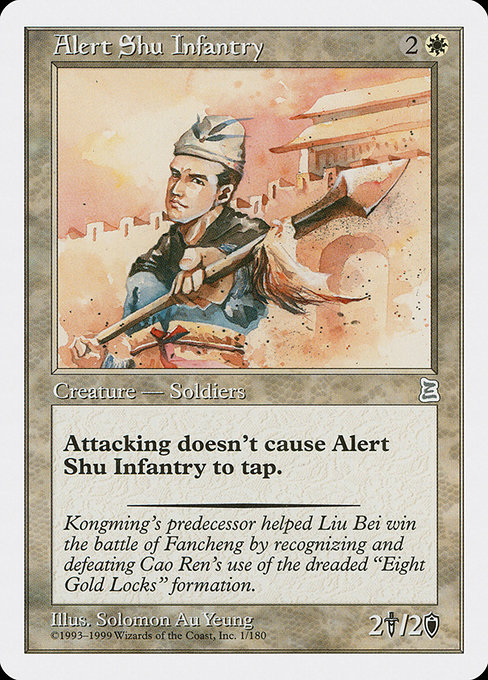

After Liu Bei’s escape, he came to the abode of Still Water, also known as Sima Hui, who advised Liu Bei to seek the talents of the Sleeping Dragon and the Young Phoenix. Excited what the counsel of these Confucian scholars might mean for his cause, Liu Bei took leave of Sima Hui and set out with Zhao Zilong, Zhang Fei, and Guan Yu to seek them out. On the way, Liu Bei met and enlisted Xu Shu as his advisor. Xu Shu helped Liu Bei defeat Cao Ren’s “Eight Gold Locks” formation.

Xu Shu felt forced to leave, however, when Cao Cao tricked him into believing his mother was in danger. Xu Shu recommended that Liu Bei continue his quest to recruit Zhuge Liang, also known as Kongming, the Sleeping Dragon.

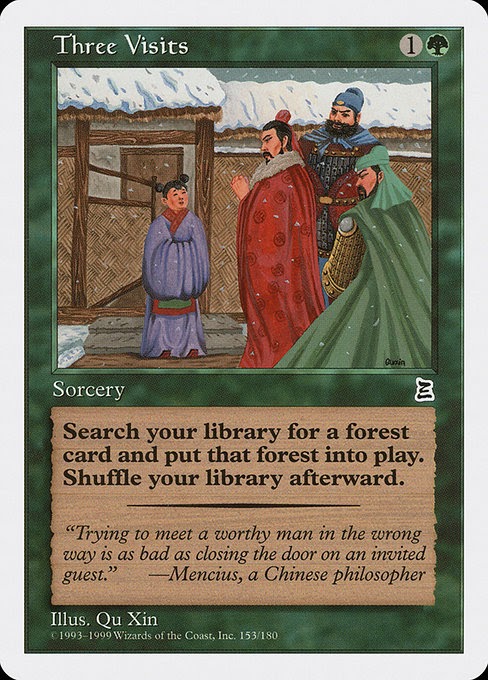

Liu Bei sought Kongming at his house, finally succeeding in meeting him after Three Visits. Kongming had been waiting for a hero to serve, already had a plan to take the capital and restore the empire. Zhang Fei and Guan Yu were suspicious, however. Kongming was only 26 years old at the time; how could be so talented? Liu Bei rebuked them: “Now that Kongming is with us, I feel as if I am a fish in water; do not be so harsh!”

Soon, Kongming had a chance to prove himself. Receiving notice that Liu Bei’s army was recruiting and drilling troops, Cao Cao sent Xiahou Dun, the One-Eyed toward Xinye with 100,000 men. Setting up a complex set of ambushes and feints, Kongming lured Xiahou Dun’s troops among a narrow path of dry reeds that were then set aflame. Xiahou Dun’s army was thrown into confusion, trampling each other to escape the rapidly spreading fire, and suffering heavy casualties as Zhang Fei, Liu Bei, and Guan Yu pursued them. Xiahou Dun and his forces limped back to Xuchang in defeat.

The victory was not permanent. Shortly thereafter, Liu Biao died, promising Jingzhou to Liu Bei; but before Liu Bei could establish control, Liu Biao’s sons surrendered to Cao Cao. Foreseeing an immanent attack, Liu Bei evacuated Xinye, leaving it empty and the gates open, except for a small force of elite troops led by Zhao Zilong.

Sure enough, Cao Ren’s army rode to attack the city, and finding it evacuated, moved into use it as a base. Just then, Zhao Zilong’s men set all but one of the Gates Ablaze, trapping the army within the burning walls of the city. Again Cao Cao’s forces trampled over themselves to escape the blaze, fleeing toward a nearby river.

Seeing it was shallow, the troops waded in. Just then, Guan Yu, who had dammed the river, let it loose, drowning countless soldiers. Kongming’s tactics had devastated Cao Ren’s forces, and the latter was forced to flee with the remains of his army.

The Battle of Changban (208 CE)

Liu Bei still had a problem: Jingzhou was nominally under the control of Cao Cao, leaving him stranded. Unable to find refuge in Xiangyang, Liu Bei started south toward Jiangling with 100,000 refugees from Xinye. Not long after, Cao Cao’s army gave pursuit and caught up to the congregation at Changban Bridge, also known as Steepslope. To protect the unarmed refugees, Liu Bei initially stayed to fight, but was forced to flee, abandoning the refugees—including his family—when the enemy army became too much for him. Cao Cao captured them all, but did not pursue Liu Bei, instead seeking to cut him off at Jiangling.

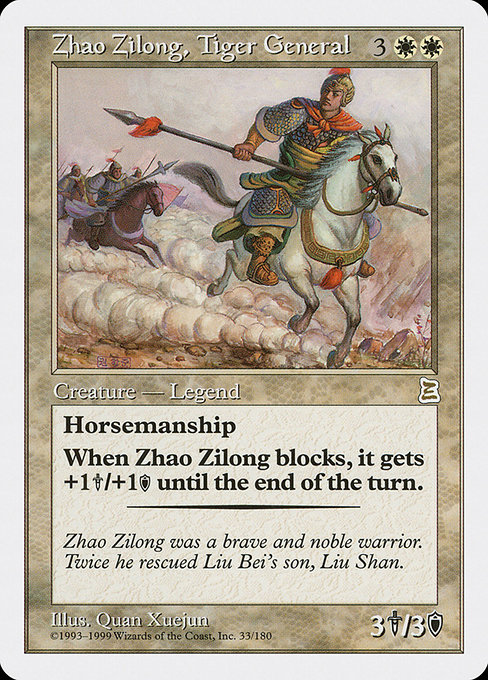

In the chaotic aftermath of the rout, Zhao Zilong had gone missing. Zhang Fei assumed he had surrendered to Cao Cao, but Liu Bei would not doubt him. In truth, Zhao Zilong was searching for Liu Bei’s family. After he returned with one of Liu Bei’s wives and a previously captured general, he earned Zhang Fei’s trust. Zhao Zilong then rode away again, in search of Liu Bei’s second wife and his young son, A’dou (Liu Shan).

In Luo Guangzhong’s romanticized retelling, on the way, he encounters a general named Xiahou En, and slays him, obtaining from him the sword named Black Pommel, the Qinggang jian. He then finds Liu Bei’s second wife and son. The wife, Lady Mi, throws herself in a well so she could not slow Zhao Zilong down, and Zhao Zilong hides the child at his chest, riding back to Liu Bei, slaying fifty officers on the way. Upon receiving his son back, he hurls him aside, upset that his son may have been the reason Zilong risked his life. Some manuscript commentators note that this gesture is to bind Zhao Zilong closer in loyalty: Liu Bei again shows that he values his comrades-in-arms over his own flesh and blood.

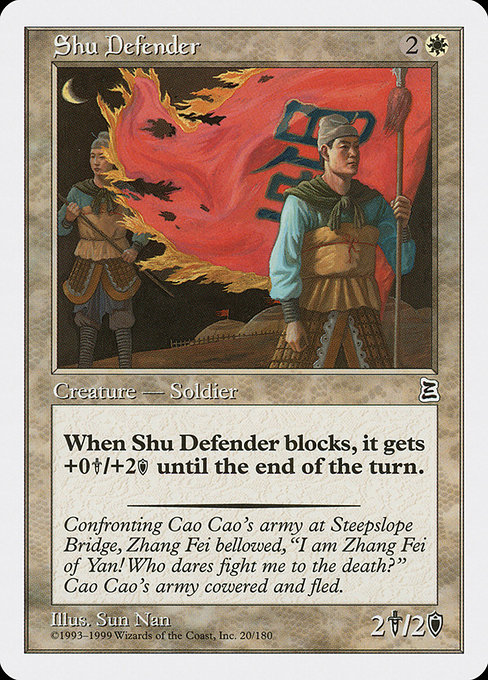

Meanwhile the army, including Cao Ren, Xiahou Dun, and Zhang Liao, had pursued Zhao Zilong. But at the bridge, the army found Zhang Fei waiting for them, “tiger-whiskers upcurled, eyes two rings of fury, snake-lance in hand.” Suspecting an ambush, and remembering Kongming’s tricks, they reined in, awaiting Cao Cao’s orders.

Seeing them hesitate, Zhang Fei bellowed a mighty challenge: “I am Zhang Fei of Yan! Who dares fight me to the death?” Thrice he bellowed, and on the third challenge, Cao Cao’s soldiers “threw down their spears and helmets and trampled over one another as they fled.” (p.323)

The Battle of Red Cliffs (208 CE)

With nowhere to turn in Jingzhou, Liu Bei now hoped to ally with the Kingdom of Wu under Sun Quan’s rule. WIth his help, Kongming convinced Sun Quan and his advisors that the Southlands could resist Cao Cao, who by this time had amassed Overwhelming Forces—a million man army.

However, the Kingdom of Wu still had one great advantage: living along the Yangtze, Wu had the strongest naval forces of the realm.

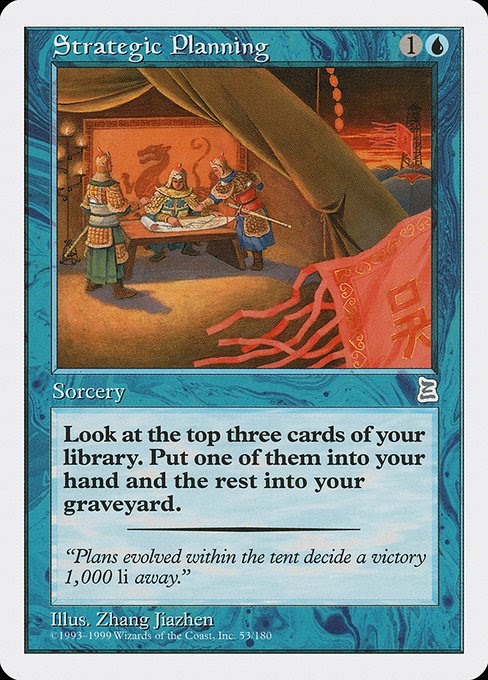

The Red Cliffs campaign proceeded initially through trickery, with both Wu and Wei employing spies and double agents. Zhou Yu, Chief Commander of Wu’s forces, was especially good at the craft of deception and misleading the enemy.

Kongming, however, could tell what was happening without any error. This enraged Zhou Yu, who was jealous of Kongming, and he schemed to find a way to have Kongming killed. Claiming Wu needed arrows, he tasked Kongming with securing 100,000 of them. If Kongming could not get them in three days, he would be executed.

With Lu Su’s help, Kongming sent a fleet of boats downstream, loaded with straw bales. In the Heavy Fog, Cao Cao’s forces could not tell they weren’t manned with soldiers, and poured volley after volley into them. In all, there were tens of thousands more than the amount requested, and Zhou Yu was flabbergasted. “Kongming’s godlike machinations and magical powers of reckoning are utterly beyond me!” he exclaimed in a mixture of admiration and despair.

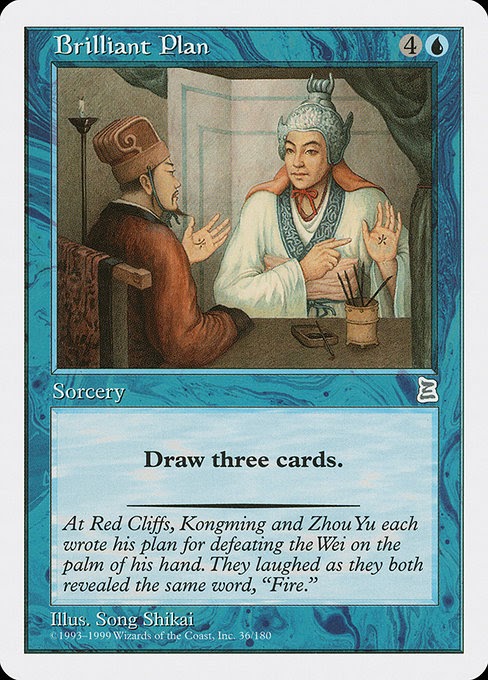

Upon Kongming’s return to camp, Zhou Yu sought his counsel. “I have one idea [about how to defeat Cao Cao’s tremendous armies], but it may not be workable. Master, could you help me decide?”

“Let us each write our ideas on our palms, to see whether we agree or not,” Kongming proposed. The two men opened their hands, and laughed. Each had written the same word, “Fire.”

It was at this point that Zhou Yu had Lu Su summon Pang Tong, called Young Phoenix, who had fled to the Southlands to avoid conflict in the north. It had been Pang Tong, secretly, that had first advised Zhou Yu to use fire, adding, “But if one boat burns, the others will scatter unless someone can convince Cao to connect his ships. . . . that’s the only way it will work.” (p. 362)

Pang Tong was to be that someone. Insinuating himself among Cao Cao’s advisors, he gave counsel to Cao Cao: “There is much illness among your sailors,” said the Young Phoenix, “there is a way to free them of their unsteadiness and seasickness.” Cao Cao listened earnestly. “Marshal your ships in groups of thirty or fifty, and bind them stern to stem and stem to stern with iron chains. If wide planks are laid so that horses as well as men can cross from ship to ship, however rough the waters, what will you have to fear?” Cao Cao was delighted with this plan, and ordered the ships bound together.

Though warned by another advisor that this strategy made him once again vulnerable to attack by fire, Cao Cao was confident. “Any attack with fire must rely on the force of the wind. Now at winter’s depth, there are only north and west winds. If they use fire, they will only burn out their own troops—what have we to fear?”

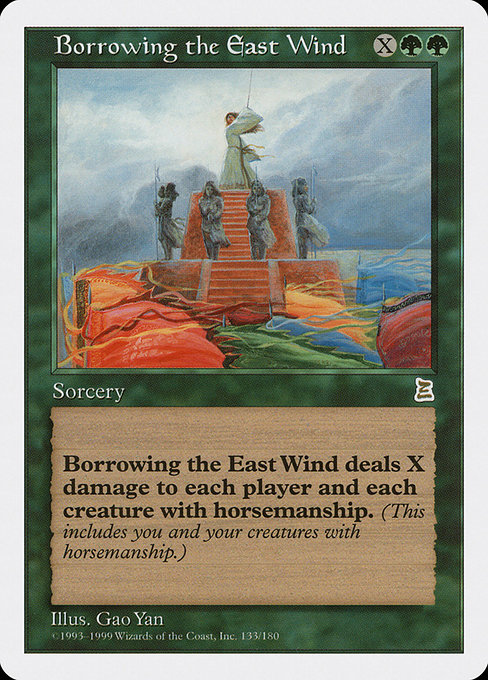

Back at his own camp, Zhou Yu was coming to the same realization, and became ill from his anxiety. Kongming was brought to tend to him. “I have a method to call forth the winds. Construct a platform, call it the Altar of the Seven Stars. From there I shall ply my magic to borrow the east wind for three days and three nights.”

Though initially delighted, when a stiff gale began to blow from the southeast, Zhou Yu’s jealousy and suspicion of Taoist magic overcame him, and he ordered his men to bring him Kongming’s head for working unnatural wonders. They were too late—sensing Zhou Yu’s intent, Kongming had already escaped with Zhao Zilong.

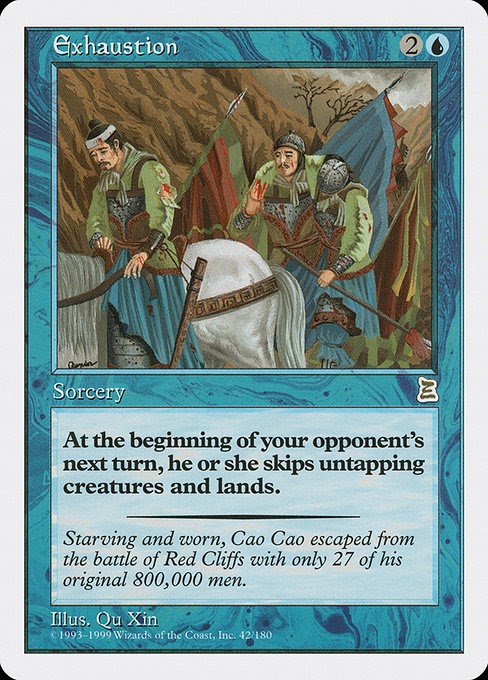

As intended, the strong east wind hastened the Wu ships toward Cao Cao’s navy. When they where just 1000m away, they set the ships alight, and like flaming arrows, they found their marks. Cao Cao’s ships locked together could not escape and were engulfed in flames. Cao Cao himself only escaped through the help of Zhang Liao and a small contingent of exhausted and wounded soldiers.

What Was Not in the Cards

This week’s episode is full of cards—so many that one can almost get the narrative beats of the Red Cliffs campaign from the flavor text alone. However, there are a few cards I’d add that represent types of cards that didn’t yet exist at the time of P3K’s design:

Echoing my previous horse design, Red Hare, this design seeks to replicate and enhance its associated card: Riding the Dilu Horse. In the story, Dilu is ridden by Liu Bei and Pang Tong, but (spoilers) saves Liu Bei and is the reason for Pang Tong’s downfall. Thus, the damage redirection ability, which can point arrows meant for Liu Bei toward the Young Phoenix. Bad fortune for Pang Tong!

The chapters this week mention two named swords that belong to Cao Cao, as well. Zhao Yun (Zilong) finds one of them, called Black Pommel, when he kills the swordbearer Xiahou En. Black Pommel is used to dispatch several generals without Zhao Yun being at all wounded, so first strike seemed appropriate.

The other, Heaven’s Brace (or “Yitian”)—named because it was said to “prop up” the heavens—remains in Cao Cao’s possession. For Cao Cao’s sword, I drew inspiration from the Sword of Light and Shadow and the Sword of Feast and Famine. The discard ability mimics that of the card, Cao Cao, Lord of Wei, and the lifegain was chosen from “light” side of Sword of Light and Shadow, evoking its “heavenly” name.

Read on!

In these sixteen chapters, roughly 120 pages, Luo narrates the preceding events and fateful battle that ultimately set the southern boundary for Cao Cao’s expansion. Decimated by the Kingdom of Wu’s naval expertise, he would be unable to conquer the Southlands. Confucian conflicts between loyalty to family and loyalty to cause (the empire) come to the fore, as seen again here Liu Bei’s willingness to abandon his family to ensure he remains alive to further the cause of preserving the Han Dynasty.

As we turn the page on chapter 50, we leave Liu Bei in a precarious position: while Cao Cao has been beaten back, Liu Bei is still without a stronghold, and in an only tenuous alliance with the Kingdom of Wu. What will become of him? Will he continue to prevail, with the help of Kongming? Find out in next week’s installment! Read on!

Recommended Media:

Luo Guangzhong, Three Kingdoms (trans. Roberts, 1991), Ch. 34-50 (pp. 262-385).

Zhang Qirong & Li Chengli, Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Asiapac Comic Series: 1995/2006), Vol. 3-4.

Red Cliff (2008), dir. John Woo. View the Trailer here.

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.