Cover art: Dong Zhuo, The Tyrant by Junichi Inoue

Read our Series Introduction and The Yellow Scarves Rebellion.

Successful in battle but without further orders, Liu Bei, his oathbrothers, and their militia set out to return to Zhuo county. However, on the way, they encountered one of the armies of the Han emperor breaking before the banner of Zhang Jue, “General of Heaven,” and leader of the Yellow Scarves. The Imperial Corps, under the command of Dong Zhuo, were being beaten down; but the intervention of the three brothers sent the Yellow Scarves into confusion, forcing them to retreat over 20km (“50 li”). Despite likely owing his life to Liu Bei and his forces, Dong Zhuo refused to acknowledge being helped by warriors without a prestigious position.

An aside: going forward, I will periodically include maps to help “locate” the action. Ancient Chinese place names are often no longer the same; many refer to administrative units that no longer exist. However, it’s my hope that with these (admittedly rough) maps, the movements of our heroes and villains will be more readily parsed. Some neat map trivia: Like modern maps, ancient Chinese maps also place north at the top of the map, as the emperor, at Luoyang, looks “down” to the south, the origin of the wind, and the majority of the empire.

The Oathbrothers’ Heroism Spurned

“Governor of Hedong [present day Yuncheng, Shanxi, in the southwest of the above map], Dong Zhuo, a native of the far northwest [present day Minxian], was a man to whom arrogance came naturally,” Luo writes. (The P3K card actually misspells Dong Zhuo’s name as Dong Zhou.) For Dong Zhuo’s disrespect, Zhang Fei was ready to kill him, but Liu Bei and Guan Yu stayed his hand, warning him that vigilantism wouldn’t be looked on kindly by the Imperial Court—a sentiment Guan Yu understood firsthand. Resolving not to remain to take orders from such a man, the oathbrothers rode until they encountered a different commander, Zhu Jun, who was engaging one of Zhang Jue’s brothers—the General of Earth, Zhang Bao.

Zhang Bao initially repelled the commander and the brothers with shamanic magic, but Liu Bei’s tactics were superior: using himself as bait, he led Zhang Bao into a pincer attack, with Guan Yu on his left, and Zhang Fei on his right. The Yellow Scarves were crushed. Zhang Bao fled, but took an arrow in the arm from Liu Bei and was forced to hide in the city of Yang while he recovered. The commander and Liu Bei put the city under siege, and the General of the Earth was betrayed by his commanders. Meanwhile, Zhang Jue had died of illness in the city of Quyang. As the Yellow Scarves faltered without their leadership, Luo describes Liu Bei, Zhu Jun, Sun Jian, and other commanders skillfully putting down the remaining rebels and quelling further uprisings. When accolades are being distributed, Luo notes that though of similar merit, the Ten initially ignored Liu Bei.

Later, however, he was granted judicial authority over Anxi in Dingzhou, where Luo acclaims that Liu Bei’s governance improved civic morality in a mere month’s time. A few months later, however, the Court began stripping officers of their titles; an inspector came to Anxi, alleging that word of Liu Bei’s accolades and imperial lineage were lies. Zhang Fei flew into a rage, dragging the inspector into the square, and administered a public beating. Liu Bei spared the inspector’s life, but the three headed west, into hiding in Daizhou (now Shanxi) until the area was beset by bandit uprisings.

Proving himself a valuable asset against bandits, Liu Bei and his oathbrothers found themselves forgiven for assaulting the imperial inspector, and Liu Bei was made magistrate over a region then called Pingyuan (now northwestern Shandong). Luo tells us that Liu Bei succeeded in bringing an atmosphere of peace to the region. But it would not last.

Dong Zhuo Seizes Power (189 CE)

It was not long after this that Emperor Ling fell ill. A question occurred over which of his sons would succeed him, Bian or Xie, born of different mothers and having different families. Emperor Ling and the Ten favored Xie, but Yuan Shao, Cao Cao, and others ensured that Bian was placed on the throne (styled Emperor Shao—no relation to Yuan Shao) in the wake of Ling’s demise. This created tension in the capital—Bian’s mother Lady He poisoned Xie’s mother, Wang, and Bian’s uncle He Jin poisoned Xie’s guardian, the grandmother of both emperors, Dong. As the stakes grew higher, Cao Cao advised He Jin, royal uncle to prince Bian, to pursue a subtle plot to kill only the most influential of the Ten, in order to bring them to heel. He Jin dismissed him, instead sending secret decrees to warlords of the kingdom.

One of these warlords was Dong Zhuo. Despite having bribed the Court to excuse his defeat at the hands of the Yellow Scarves and having been granted mercy, Dong Zhuo is said to feel no loyalty to the emperor, being only interested in personal gain. Thus, he answers He Jin’s decree by sending a letter back, offering to take care of the Ten, and leading an army toward the capital of Luoyang.

Dong Zhuo’s reputation preceded him, however; the court censor advised preventing him from entering Luoyang, saying, “Dong Zhuo’s a jackal. Let him into the capital and he’ll devour us.” The presence of Dong Zhuo’s approaching army alerted the Ten to He Jin’s intentions, however, and the Ten ambushed and killed He Jin. This spurred Yuan Shao and Cao Cao, who had with them a retinue of soldiers, to storm the palace, putting the Ten to the sword.

In the chaos, the young Emperor Shao (Bian) and his younger brother, the prince of Chenliu (Xie) fled into the path of Dong Zhuo. Using this fortune to gain entry into the capital, Dong Zhuo began destabilizing the city, intimidating its people, finally seizing power by deposing Emperor Shao and installing his nine-year-old brother, Xie in his place as the newly-styled Emperor Xian.

With the newly enthroned Emperor Xian (formerly Xie) installed, Dong Zhuo availed himself of the riches of the palace. Luo writes that he “began to indulge himself freely, debauching the imperial concubines, and sleeping in the Emperor’s bed.” Seemingly for sport, Dong Zhuo razed the nearby village of Yang, plundering it of its valuables and murdering all the male inhabitants. This act of brazen evil began to foment talk of murdering Dong Zhuo among Yuan Shao, Cao Cao, and minister of the interior, Wang Yun.

The War Against Dong Zhuo

Cao Cao initially thought to assassinate Dong Zhuo with a jeweled blade, but lost his nerve, instead presenting the blade to Dong Zhuo as a gift in order to hide his intent. Suspecting he might be found out, Cao Cao fled the Court, and driven by his paranoia, killed a man who had offered him shelter. Luo means to tell us with this action that Dong Zhuo and Cao Cao are alike in having a “bane-filled mind.”

Arriving safely to his home in Chenliu (southeast of Luoyang, in Yan Province), Cao Cao forged a summons, gathering a coalition army under the leadership of Yuan Shao. Though historically, Liu Bei did not participate in this effort, Luo puts him and his oathbrothers here, noting that due to his lineage, Yuan Shao and Cao Cao accept him as one of them.

Just then, the mighty warrior Hua Xiong appeared at the gates of their camp, issuing challenges. Guan Yu stepped forward, volunteering to slay Hua Xiong. Despite the incredulity of Yuan Shao and others that a lowborn warrior would be so bold, Cao Cao urged that Guan Yu be allowed to answer this challenge. “If I fail,” Lord Guan said, “My head is yours.”

Guan Yu’s battle is presented in the language of theophany, the sudden appearance of the divine:

Cao Cao had a draft of wine heated for Lord Guan before he mounted. “Pour it,” said the warrior, “and set it aside for me. I”ll be back shortly.” He leaped to his horse, gripped his weapon, and was gone. The assembly of lords heard the rolling of drums and the clamor of voices outside the pass, and it seemed as if the heavens would split open and the earth buckle, as if the hills were shaking and the mountains moving. The terror-struck assembly was about to make inquiry when the jingling of the bridle bells announced Lord Guan’s return. He entered the tent and tossed Hua Xiong’s head, freshly severed, on the ground. His wine was still warm. (p. 44)

Encouraged by Guan Yu’s victory over the enemy commander Hua Xiong, Zhang Fei characteristically urged immediate action. Dong Zhuo had moved an army of 50,000 to the Si River while he and his adopted son and bodyguard, Lü Bu, guarded Tiger Trap (Hulao) Pass with an army of 150,000.

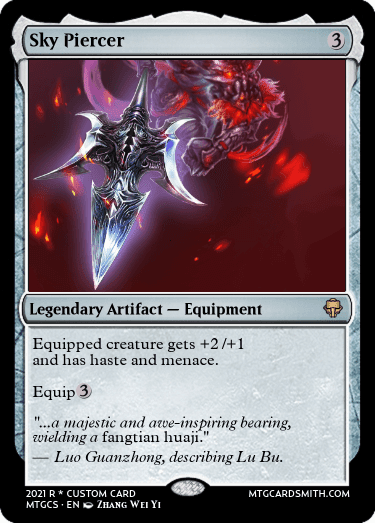

Lü Bu was known to be an amazing warrior, but selfish, impulsive, and shallow: he murdered his previous adoptive father and joined Dong Zhuo in exchange for wealth and the gift of the fine horse Red Hare. As Lü Bu takes the battlefield, Luo describes his raiment and affects in great detail:

A three-pronged headpiece of dark gold held his hair in place. His war-gown is of Xichuan red brocade with a millefleurs design. Armor wrought of interlocking animal heads protected his torso. A lion-and-reptile belt that clinked and sparkled girt his waist and secured his armor. A quiver of arrows at his side, a figured halberd with two side-blades clenched in his hand, Lü Bu sat astride Red Hare as it neighed like the roaring wind. Truly it was said: “Among heroes, Lü Bu; among horses, Red Hare.” (p.45)

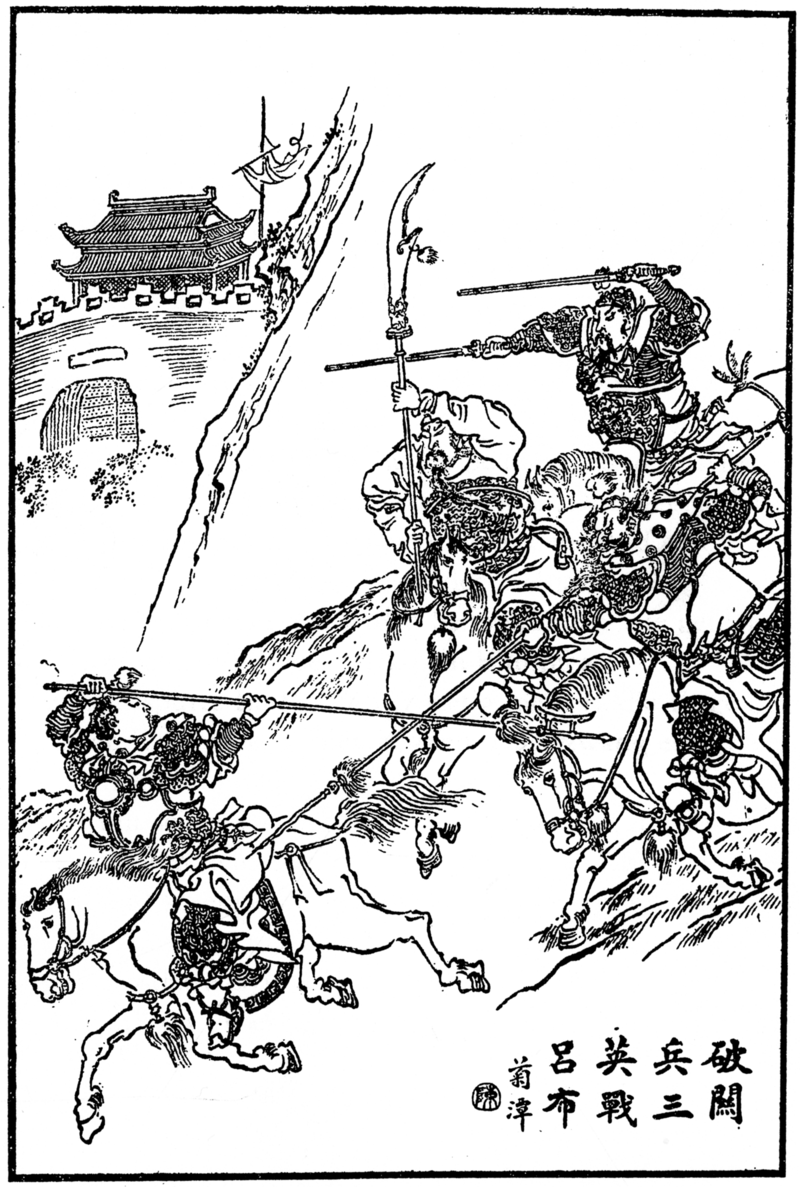

Though the warrior is a fearsome sight, Zhang Fei rides out in fury. The warriors clash again and again, over fifty bouts, without either emerging victorious. Guan Yu joined, and after thirty more bouts, still, there was no victor. Finally, Liu Bei entered the fray wielding his twin swords, and Lü Bu was forced to flee the field.

A Qing Dynasty rendering of the Battle at Hulao Pass

Zhang Fei’s pursuit was stopped by a hail of arrows and stones, but the morale of Dong Zhuo’s army had been wounded. Hoping to avoid further defeat, the forces of Dong Zhuo retreat back to the capital, with Yuan Shao’s coalition on their heels.

What Was Not in the Cards

One of the key things I notice when I look at Portal Three Kingdoms cards is the high mana costs. Both Yuan Shao and Lü Bu would be more palatable within the set if their mana costs were reduced by one or even two, or with the addition of abilities that reflect the characters’ personalities. Yuan Shao, the Indecisive might have a conditional attack trigger: “Flip a coin; if you lose the flip, untap Yuan Shao and remove him from combat.” This potential drawback could justify decreasing his mana cost to 2R.

As for Lu Bu, Master-at-Arms, evasion and haste are solid, but six mana for a 4/3 doesn’t feel great on a rare and legendary card. Because of his penchant to switch allegiances, what if we decreased his mana cost to four, but added a Ghazban Ogre clause—the player with the highest life total gains control of Lü Bu every end step? These characters thus retain their chaotic “red” nature, but also gain abilities that more thoroughly reflect how Luo represents them in the narrative.

This week, I’ve got a couple more pieces of legendary equipment as well. For Lü Bu’s ji, Sky Piercer, I took a look at a number of Magic’s halberds and axes, especially Rosethorn Halberd and Obsidian Battle Axe. These cards all seem to increase power by 2 or 3 and toughness by 1 or 0, sometimes having additional abilities. Not wanting to create something broken, or cards that might encroach on future design space, I’ve kept these fairly simple.

For Sky Piercer, I wanted the famous polearm to reflect the explosive power of Lü Bu on the battlefield, so I gave it the power to grant haste and menace. I’ve left the casting cost at 3 generic mana, though I could see changing it to 1RR or 2R, restricting these abilities to red.

I didn’t design a weapon for Liu Bei last week, so this week I’ve added his twin blades to the “remastery” card pool. Deviating from the lore, where they remain unnamed; I’ve dubbed them “Spring and Autumn,” after the time period during which Confucius is said to have lived, since Liu Bei was said to have a ruling style that appeared Confucian. Likewise, due to his famed emphasis on benevolence, I appended Holy Strength as the bonus to power and toughness. The abilities I put on this card are intentionally “white,” to harmonize with Liu Bei’s card; like with Sky Piercer, changing the mana cost to include white mana might be a good decision.

Read On!

In this week’s summary of just four chapters, we got a closer look at our characters’ personalities. If I were, at this juncture, to imagine D&D alignments for them according to Luo’s portrayal, Dong Zhuo is chaotic evil, Cao Cao is lawful evil, Lü Bu is chaotic neutral, Zhang Fei is chaotic good, and Liu Bei is lawful good. Next week, we bring the story of the war against Dong Zhuo to a close, and look at some ideas for some non-equipment cards to add to our fictional “remastery” of the set.

Recommended reading:

Luo Guanzhong, Three Kingdoms: A Historical Novel, translated by Moss Roberts, Chapters 2-5 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), pp.14-47.

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.