Here begins our tale

The empire,

Long divided, must unite;

Long united, must divide;

Thus it has ever been

—Luo Guanzhong, Chapter 1, Moss translation

Luo Guanzhong’s opening lines are deeply spiritual—or philosophical, if you like. To those familiar with East Asian religion and philosophy, especially Taoism, they evoke the notion of yin and yang, the cyclical churning of winter and summer, chaos and order. Chinese philosophy, particularly Taoist, Confucian, and Legalist theory, suffuses his retelling of the Three Kingdoms and the Magic set based on it.

The story of the Three Kingdoms begins with a flurry of natural disasters: inside the throne room of the emperor, a strong wind blows, and the apparition of an emerald snake coils around the throne. Storms bring hail, and an earthquake results in a tidal wave that sweeps many people along the coast out to sea. There are avalanches and rockslides in the mountains. The emperor is said to have been nonchalant at the news of so much suffering.

The decadent emperor’s authority weakens as Corrupt Eunuchs gain de facto Control of the Court at Luoyang. The Eunuchs here are as much an ancient literary device as they are a feature of a number of historical courts. By invoking eunuchs, the machinations of the empress, natural disasters, and so on; Luo, in the patriarchal manner of his time, conveys that the “Yang” of masculinity and order is reduced, given over to the “Yin” of femininity and chaos. The themes of apathy and decadence will return again as well, as traits that lead to suffering among the people and the downfall of rulers.

The Yellow Scarves Rebellion (184 CE)

In the north, a healer named Zhang Jue encountered the fabled Taoist sage and saint Zhuangzi, who bequeathed unto Zhang an ancient text, and warned him to think no seditious thought, lest he suffer retribution. After this warning, the sage then disappeared into a “puff of pure breeze.” The significance of this appearance is made more apparent if we understand that Zhuangzi’s lifespan was roughly contemporaneous with that of Mencius, or Mengzi, as well as Plato and Aristotle—roughly 500 years prior to the events of this story! It also becomes significant in a dialectic that we’ll see introduced again below: the tension between understanding Taoism as offering a path of humanism and naturalism, on one hand, or a more spiritual mysticism, on the other.

Unlike modern scholarship, which reads the texts of Zhuangzi as naturalistic and humanistic, scholars of Luo’s time read Zhuangzi as a mystic, offering Zhang Jue a kind of sorcery to aid his practice of medicine in assisting the suffering peasants of the empire. With these teachings, Zhang Jue and his brothers began practicing an almost “evangelical” form of Taoism, gaining the favor of the populace because of their aid efforts, and preaching that a time of renewal would come.

In the wake of government corruption and widespread natural disasters, famine, and pestilence, people came to believe that the emperor has lost the Mandate of Heaven. They believed the old regime, symbolized by the element of fire and the color red, would fall away, and that a “yellow heaven” (representing the element of earth, and healing) would come to replace it.

Noting the unrest, and sensing he had popular support, Zhang Jue violated Zhuangzi’s warning by giving in to seditious thoughts and plotting insurrection. His plan was almost immediately exposed, but support for the uprising was immense—half a million people tied yellow scarves around their heads and marched in such force that they scattered Imperial troops before them based on the mere rumor of their approach. Thus, a frantic call went out for all warriors loyal to the throne to volunteer to serve in putting down the massive rebellion. This call would be posted in Zhuo county, where Xuande, also called Liu Bei, would see it.

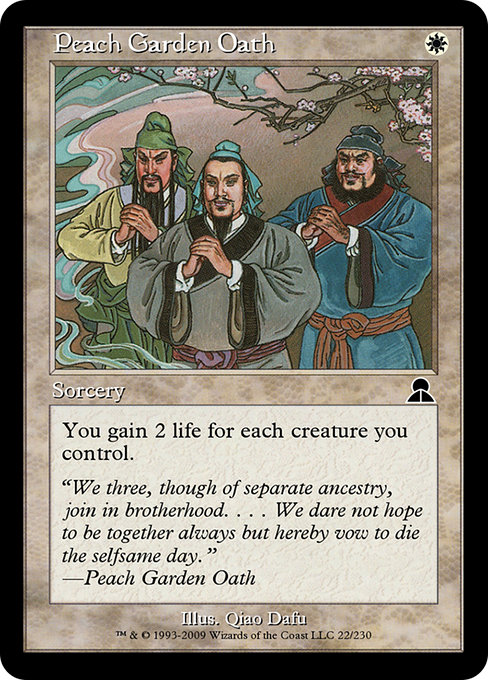

The Peach Garden Oath

Liu Bei is introduced as one of the main protagonists of Luo’s novel. His courtesy name, Xuande, can be read as symbolic, being a compound of the words for “dark red” and “virtue,” possibly indicating that Liu Bei carries forward the virtue of the current Han regime. Liu Bei himself is the heir to an impoverished branch of the imperial line, descended from a Han emperor several generations back. Luo tells us that a fortune-teller once foretold that his house would produce “an eminent man.”

Returning to the dialectic between humanism and mysticism mentioned above, Luo mentions that Xuande was educated in traditional schools of moral philosophy, which disdained portents and mysticism. In this way, Liu Bei represents an antithesis to Zhang Jue: Liu Bei is a humanist and a naturalist, who embodies the promise of reform of the old dynasty and the virtue of order, while Zhang Jue is a mystic, embodying the spirit of revolution and chaos.

As Liu Bei was reading the Imperial Recruiter’s notice, a wealthy local farmer, Zhang Fei, called to him, and suggested that they join forces to put down the Yellow Scarves. As the two toasted their new friendship in a nearby tavern, Guan Yu strolled in, explaining that he was also answering the call for warriors, having been on the run for five years for acting as a vigilante and killing a corrupt magistrate. Becoming fast friends, the three agreed to go to the peach garden at Zhang Fei’s farm to make a sacrifice, and pledge their loyalty to one another.

Using the sacrificed bull as the occasion for a feast, the three recruited hundreds of local youths and procured horses, armor, and their legendary signature weapons: twin swords (双股剑—shuang gu jian) for Liu Bei, the Green Dragon Crescent Blade, named “Frozen Glory,” for Guan Yu, and a serpent-headed spear over 4m long for Zhang Fei.

The trio immediately put these weapons to use, riding out with their soldiers, with Zhang Fei impaling one Yellow Scarves commander and Guan Yu slicing another in two. Leaderless on the battlefield, the Yellow Scarves forces scattered before them. They had continued successes in subsequent battles, but were ultimately denied the recognition and honors granted to many other commanders because of their low station, and the corruption of the group of Eunuchs known as the Ten. Rather than engage in corruption and bribery to appease the court, Liu Bei disbanded the majority of his militia, and returned to the north with his oathbrothers.

The Mysterious Cao Cao

Late in chapter one, we are also introduced to Cao Cao, also called Mengde—his names have mixed connotations, alluding either to integrity and virtue, or manipulation and deception, depending on who is telling the story. This ambivalence is echoed in a fortune-teller’s prediction of Cao’s destiny: “You could be an able statesman in a time of peace or a treacherous villain in a time of chaos.” Luo makes certain to tell us that Cao Cao was happy to deceive his father and his uncle, and used this deception to live a licentious youth, full of entertainment and wild schemes, but that he was nevertheless widely commended for “filial devotion” and integrity.

Because of this commendation, Cao Cao was given a post as commander of security near the capital of Luoyang, enforcing the laws with severe beatings, and showing no preferential treatment for the well-connected. The respect he earned in this post warranted his promotion to magistrate of a nearby city, and later, to commander of the cavalry in Yingchuan, where he won a series of battles against the brothers of Zhang Jue, the Yellow Scarves’ leader. As the story pivots to the aftermath of the rebellion, we are told that Cao Cao received a generous commendation, where Liu Bei was passed over—reiterating that Cao Cao is someone on the inside, and Liu Bei is the outsider, or underdog.

What Was Not in the Cards

Portal Three Kingdoms represents the Yellow Scarves as being a capable offensive force, evasive when on the attack, but—as with history—collapsing when they meet skilled resistance. Last fall, Landon Crispens over at TCGPlayer noted that Yellow Scarves Cavalry is one of the most evasive creatures red has under three mana; while that may be true, were I remastering this set, I’d consider either dropping that mana cost to a single red (bringing it in line with black’s Tormented Soul) or adding haste. While we’re at it, these “soldiers” were historically also “rebels,” so appending that to their creature type to increase the amount of possible rebel decks seems like a promising edit as well—Boros or Mardu Rebels sounds awesome!

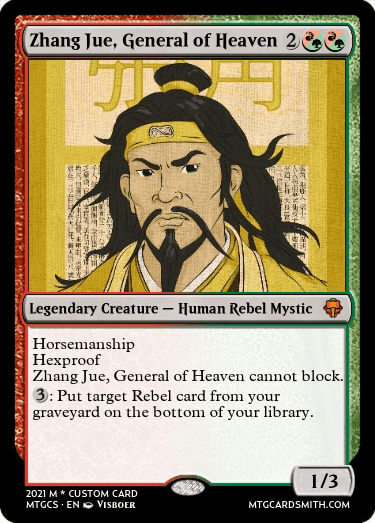

Finally, it seems odd that while Yellow Scarves General exists, it’s at best a sturdier version of the cavalry. “The General of Heaven,” Zhang Jue himself, has no legendary card of his own. To amend this, I’ve created this design:

Zhang Jue was a Taoist mystic, healer, and rebel general; I borrowed the abilities of Yellow Scarves General, Taoist Hermit, and Lin Sivvi, Defiant Hero to express his place at the confluence of several roles. I gave him a hybrid mana cost with green, because Taoist Hermit and Taoist Mystic are both green, indicating that at least for the purposes of this set, Wizards thought it best to associate Taoism with that color.

Another glaring omission, when P3K is compared to contemporary Magic, is equipment. Like many ancient or even modern fantastic stories (The Sword in the Stone, the Song of Roland, The Lord of the Rings, etc.), the presence of legendary weapons is conspicuous. Over a half-dozen named weapons exist, and numerous lines in the Romance make reference to the type and style of weapons being wielded by combatants. In 1999, we didn’t yet have equipment, but that doesn’t have to limit us in 2021. In chapter one of Luo’s novel, we see three legendary weapons procured and two put to use—Zhang Fei’s Serpent Lance and Guan Yu’s Green Dragon Crescent Blade.

For Zhang Fei, who is often first on the attack in the Romance, I’ve imagined a strong, if not terribly flashy, card to represent the eighteen-span serpent headed spear. The flavor text is taken from the Roberts translation of Luo’s novel, right after Zhang Fei and Guan Yu dispatch some Yellow Scarves commanders. For the mechanics, I looked at previous iterations of spears—especially Jousting Lance, Runechanter’s Pike, and Shadowspear:

The blade mentioned in the flavor text is Guan Yu’s Crescent Blade, the same one depicted on the card Wielding the Green Dragon. Guan Yu’s weapon is perhaps the most prestigious of all the weapons in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, remaining part of his iconography to this day:

In designing this equipment, I turned to Chinese numerology. The original card, “wielding the Green Dragon,” gives a creature +4/+4 until end of turn, but four is considered almost universally unlucky in China. However, eight is lucky—in Taoism it represents wholeness. Thus, the casting and equip cost here combine to total 8, the stat boost totals 8, and when equipped to Guan Yu, Sainted Warrior, his stats become 8/8.

This card’s abilities are a mechanical reference to Juggernaut, as well, and when equipped to Guan Yu, the 8/8 Trample body is meant to evoke the Force of Nature—fitting for a character who is sometimes hailed as the “God of War.” Trample and horsemanship might not be tremendously synergistic outside of the set, but within the set, Guan Yu’s Frozen Glory should be able to cut through and past an intercepting general with relative ease. Incidentally, in addition to Dynasty Warriors: Destiny of an Emperor, which was released on April 29, this year has also seen the release of the film Green Dragon Crescent Blade, a story focusing on Guan Yu:

A promotional Poster for Green Dragon Crescent Blade (2021)

Read On!

Like a serialized comic book or two-part episode of 1966’s Batman with Adam West, Luo likes to end chapters of Three Kingdoms on cliffhangers, encouraging his readers to keep going to find out what happens next. So tune in next time to find out how the Yellow Scarves Rebellion is put down, and whether the efforts of Liu Bei, Zhang Fei, Guan Yu, and Cao Cao are enough to stabilize the crumbling Han Dynasty, in “The Fall of the Han Dynasty Part 2: Enter Dong Zhuo!”

Recommended Reading:

Luo Guanzhong, Three Kingdoms: A historical Novel, [unabridged version] trans. Moss Roberts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), chapter 1 / pp. 5-13.

Wang, Robin R., Yinyang: The Way of Heaven and Earth in Chinese Thought and Culture. NY: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

SY, “Yellow Turban Rebellion,” World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 12 Dec 2019. Web. 18 May 2021.

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.

Cover art: “Control of the Court” by Li Yousong