Cover art: “Balance of Power” by Quan Xuejun

Despite its allegedly not being released for the American market, one spring day in 1999, I remember parking my bicycle outside of Baseball Card Connection in the town square of Effingham, Illinois and walking in to see the newest Magic set: Portal Three Kingdoms. While the Portal sets were known to be ostensibly less powerful—designed for teaching, not competition—something about the flavor of this set grabbed me. Like Arabian Nights, Portal Three Kingdoms is based on real-world sources.

While I knew Arabian Nights’s stories mostly through cartoons like Popeye, Bugs Bunny, and Disney’s Aladdin; the massive historical novel Portal Three Kingdoms is based on, Luo Guanzhong’s Romance of the Three Kingdoms, had inspired video games that I was familiar with. Destiny of an Emperor on the NES and the Dynasty Warriors series on Playstation were stories of historical warfare that centered on the destinies of larger-than-life characters with named mounts and legendary weapons and the potential for heroic feats that would unite the kingdoms and restore peace to the land, everything this D&D nerd could ask for. The allure of the massive Zodiac Dragon in the singles case didn’t hurt, either. An 8/8 that comes back to hand when it dies? 16-year-old me was here for it.

So, with my limited paper route funds, I picked up two of each Kingdom’s respective pre-constructed decks and the starter set, and set about teaching friends to play Magic, getting games between Scholastic Bowl matches in high school hallways and stairwells. Fond memories of these games are what motivated me, two decades later, to start re-collecting Portal Three Kingdoms, and this year I’ve spent time both learning the history and lore of the set, as well as imagining what a contemporary Remastered version of this set might look like. This article is the introduction to a series retelling one of China’s most popular stories through the Magic: the Gathering set Portal Three Kingdoms.

A Story Untold

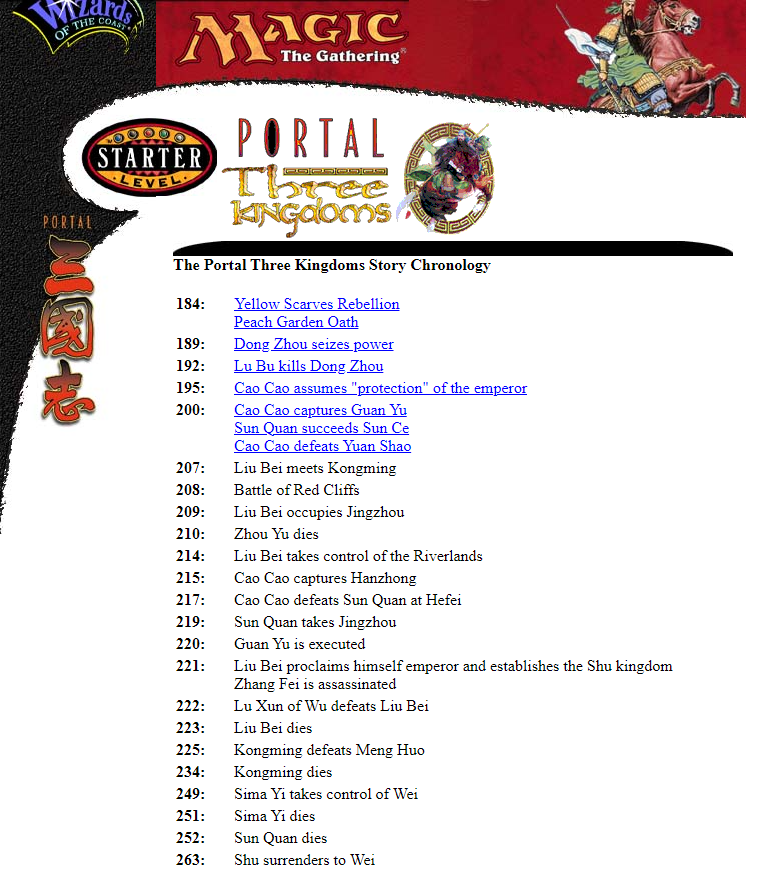

Why bother with a retelling? Quite simply, as far as the Magic set is concerned, there was never much of a telling. While the original page is no longer live, at the time of P3K’s release, Wizards had set about summarizing the 120-chapter novel on their website. Perhaps due to the sheer length of the novel and the ever expanding cast of characters, the summary was never finished. Five entries on the P3K Chronology have linked summaries, leaving nineteen events conspicuously without explanation.

A screenshot of the Portal Three Kingdoms Story Site, available on archive.org

This is understandable; reading the 1000-page novel and summarizing the shifting, Byzantine path of alliances and feuds between over 100 named figures over 100 years of war is a monumental task. Furthermore, the set was designed for the Chinese market in 1999, when the internet was far less ubiquitous—I didn’t have regular internet access until 1999; spending lots of time building a website for the non-target demographic was probably not something Wizards wanted to do when those resources could be better spent promoting Urza’s Destiny and the Sixth Edition rules changes.

While Magic was beginning to tell more involved stories, especially with the Weatherlight Saga, these stories were usually communicated through very short storybooks included in starter decks, or on the cards themselves. Magic novels didn’t really start engaging the plot of the sets themselves until 1998’s The Brothers War, which fleshed out the then four-year-old Antiquities and tied a sequence of novels to the “Urza’s” block. All this to say, though lamentable, it was very understandable and unremarkable for the time that Wizards of the Coast did not tell the story of these cards.

Neither interest in the cards nor in the story they are based upon have abated however. As far as the cards go, Portal Three Kingdoms reprints continue to trickle into “masters” sets, with Rolling Earthquake and Imperial Recruiter showing up in Double Masters. The scarcity of English edition cards from the original 1999 release has nevertheless kept the hard-to-find original printings at premiums worthwhile only to dedicated collectors.

Where the story is concerned, adaptations of this historical period and the later novel by Luo Guanzhong continue to show up on consoles and at the box office. The 2008 film Red Cliff dramatizes a famously deadly battle that solidified the existence of “three kingdoms” for decades in the third century; and on April 29, 2021, China saw the release of Dynasty Warriors: Destiny of an Emperor, a heavily fictionalized wuxia retelling the broader story based upon the eponymous video game adaptation.

A poster for 2021’s Dynasty Warriors: Destiny of an Emperor.

An Unusual Set

Learning about Tempest Remastered on MTGO was the initial impetus behind the speculative facet of this article series; additional entries on Arena with Amonkhet and Kaladesh, and in paper with Time Spiral Remastered pushed a question to the forefront of my mind: “What if P3K been made with or was expanded and tweaked with contemporary sensibilities?”

Portal Three Kingdoms is an oddity, and gives us a lot of avenues to imagine and re-imagine; as far as Magic: The Gathering sets go, it has massive potential for expansion into new design space. For example, one of the hallmarks of Portal is the limitation on card types—there were only three: lands, creatures, and sorceries. For the sake of teaching the game mechanics to total beginners, in P3K, there are no enchantments, artifacts, non-basic lands, or instants. In effect, this creates a Hearthstone-like experience where interaction mostly occurs during combat or not at all. I say mostly, as counterspells and combat tricks exist, but as sorceries like Extinguish that explicitly say when they can be played.

Thus, just by thinking about card types, we start to imagine what might have been: equipment representing signature weapons? Lands for famous locales? Sagas for important narrative arcs? One can easily think of all of these fitting and operating well within P3K. Guan Yu’s Green Dragon Crescent Blade would make a fantastic legendary equipment:

As might be expected for an older set, the color pie is bent sometimes in one direction for flavor, and other times in the other direction for mechanical reasons. Rather than fitting characters to the colors, the colors seem chiefly partitioned among the three kingdoms and other warring factions, and historical figures that belong to those factions—regardless of their historical personalities—are assigned a color based on this. For example, Shu Kingdom is given the color white, perhaps to reflect the emphasis Luo puts on Liu Bei’s virtue in the novel. Cao Cao, a poet, warrior, and leader of Wei, is assigned to black, likely because of his portrayal as a villain in Luo’s telling, and so all his associates are as well. Red contains figures from the earlier stages of the story who never become part of the later Three Kingdoms, and Green contains figures from the latter part of the story who weren’t explicitly affiliated with one kingdom or another.

From a gameplay standpoint this rather “cookie-cutter” approach is convenient: one can play the mono-colored Wei, Wu, and Shu-themed precons against one another without the worry of mana-fixing. From the perspective of historical flavor and contemporary playability in formats like Commander, this sequestering of colors within the kingdoms leaves much to be desired. Mechanically, the abilities that fall within these colors’ portfolios sometimes align with something a particular character in the associated kingdom might have done, but other times, leave us wanting much more. For example, Kongming, Sleeping Dragon was a strategist, and he provides an anthem effect, which makes some sense—his presence makes everyone better in combat. Lady Zhurong, Warrior Queen of the barbarians, is green and simply has horsemanship.

Kuniyoshi Utagawa, “Lady Zhurong fighting against the enemies,” 1854.

Someone as cool as Lady Zhurong deserves better than simple “horsemanship.”

The strangeness of this set is compounded when one looks at the sheer ratio of legendary to non-legendary creatures: Just over one in six cards Portal Three Kingdoms is a legendary creature; one in three creatures is legendary. This is roughly the same ratio as the set that introduced the legendary supertype, Legends; our most recent “legendary matters” set, Dominaria, with its “legendary matters” theme, has only a slightly smaller ratio.

Furthermore, as alluded to previously, Portal Three Kingdoms is the second and also last set to be taken directly from a work of real-world fiction, the first being Arabian Nights. While other sets feature numerous references to or obvious examples of inspiration being drawn from everything from classic mythology and literature (e.g., Lorwyn, Amonkhet, Eldraine, Theros, and Kaldheim) to horror and kaiju films (e.g., Innistrad and Ikoria), these sets are recreations of characters and events from these works that fit dubiously into Magic’s canonical multiverse, if at all. And unlike Arabian Nights, which is replete with Djinni, sorcerers, ogres, and the like, the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, while fictionalized, is still a relatively non-supernatural story by comparison.

A few characters—Taoist sages like Kongming and Zhang Jiao—call upon or make reference to powers beyond themselves that may subtly influence events, but for a game called “Magic,” in Portal Three Kingdoms, there is surprisingly little to be found. Apart from a few exceptions, most sorceries reference battle tactics and events of the historical period dramatized in Luo Guanzhong’s novel.

Scouting Ahead

The series that this article inaugurates will not look like this article. Instead, expect storytelling—a summary of Luo Guanzhong’s novelization, as told through the cards of Portal Three Kingdoms—with commentary detailing the meaning of the story to its readers, and supplementary content, like “what if?” cards and deck ideas. In 1999, Wizards only made it through around a quarter of the story of the Three Kingdoms, leaving many cards unexplained. In an effort to avoid a similar outcome, I may give short shrift to some aspects of the story, favoring explaining the cards over giving a more full account; in these instances, I shall provide interested readers with instructions on where to read what was glossed or skipped. It’s my hope that this series will be educational, enjoyable, and spur you on to more enjoyable games.

Join me next time for Chapter 1: The Fall of the Han Dynasty!

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.