After a year of binging Arena, I’ve fallen head over heels all over again with cube drafting. Cubing with folks online isn’t the same as drafting in person, but it’s absolutely the kind of Magic I’ve sorely missed and rekindled so much of my excitement for the game.

This week, I’ve got two such drafts lined up, including one tonight with a kind of cube I’ve never encountered—Jonathan Brostoff’s ETB Cube, where every creature has an Enters The Battlefield effect. While I don’t always prepare in advance, I do enjoy reading cube lists first fun—especially unusual cubes. So today, I figured why not have you ride shotgun as I skim the list and get in about ten minutes of preparation for what’s sure to be a wild ride? Here’s what goes through my mind when I’m evaluating any cube list, as well as my expectations for how tonight might go based on Brostoff’s list.

The Big Picture

The first things I do before looking at the cards in a cube is peruse the overview (or if it’s a paper list, ask the creator these questions). Most of the time, this a fast step. The majority of cubes I’ve encountered follow similar constraints—they usually contain between 360 and 720 cards, are optimized for eight people to draft, and have no special rules. However, many cubes deviate from that norm in ways that create wholly different and exciting experiences.

Things to look for include:

- Is the cube not designed for booster draft? Is it intended for a different number of drafters than 8? For example, Derek Beginner’s Cube is designed for two players to grid draft.

- Does the cube provide anything in addition to basic lands? Some provide snow basics, Wastes (Sniffygull’s Monkey Cube does this), or even guildgates.

- Are colors missing? As with Elizabeth Rice’s Temur Cube.

- Are there special rules? Some cubes fundamentally change how some or all cards work, like providing four copies of Squadron Hawk if you draft one copy. Or there’s Anthony Mattox’s Turbo Cube, which modifies all cards with double Heartstone and Helm of Awakening (I would love to play this one day).

This information is critical, since it drastically changes how cards function. There are other things you could look into before perusing the card list (or jumping straight to drafting), but I prefer to figure these out for myself or ask after reading the list/starting to draft. These questions include:

- How many cards in are the cube? Most cubes for 8 person booster draft range between 360 (where every card is guaranteed to show up) and 720 (where there’s more variance in games). It’s harder to assemble combos in larger cubes and they tend to feature larger swings in power level between cards, but smaller cubes can become stale much more quickly.

- Is the cube singleton? The default for cubes is in line with Commander’s primary constraint—each card only shows up once. But a default is not a rule.

- Are there any constraints? Some cubes only have commons or uncommons, like Hugh Kramer’s common and uncommon cube through which I won and regifted a Taiga.

- What are the intended archetypes? If a cube uses a lot of cards you’ve never seen before, it can be really helpful to know the archetypes to help guide you through a draft.

Again, I generally don’t ask any of these questions before looking at a list or an important question comes up during draft. I never ask what the intended archetypes are, since I trust myself to recognize them. Moreover, each draft serves as a playtest for whether these archetypes are visible to drafters and viable for play. That said, some people really benefit from knowing in advance. I encourage you to ask all the questions that will help you feel comfortable—trust me, there’re few things cube designers enjoy more than talk about their creations.

Cube-Breaking Heuristics

As a cube designer, I fall for all the traps in curating my cube. I fail to cut overly weak pet cards because I love them (Ojutai Exemplars was in my cube for years without ever being put in a deck). I include overpowered cards that invalidate entire strategies (happens a lot if you have a lower powered cube and experiment frequently with new cards). I support weird archetypes that people struggle to see and that struggle to compete against tried-and-true strategies like Monored aggro, Green multicolor ramp, and Planeswalker control. It’s hard to judge your creation objectively when it’s a product of your inspiration and care. Game designers know this problem all too well, and that’s why we ally ourselves with playtesters.

As a cube player, I embrace my role as playtester. I don’t merely strive to have fun, I want to see if my draft can answer questions—both to provide its designer with information and enhance my own understanding of cube design. I still play to have fun, but as a Timmy/Spike, I’m looking to have fun while winning. To that end, I have a few heuristics I employ while scanning card lists:

- Which cards seem out of place? Some cards are substantially stronger or weaker than other cards in the cube. Some cards aren’t often included in cubes and suggest an unusual archetype. These can signpost unusual archetypes or be awkward inclusions.

- Is there something missing? Some cubes deviate from the norm by eschewing staple effects like cheap red creatures, green ramp, or planeswalkers. Those are totally cool decisions, but they can change how other cards and archetypes function. If something is missing, how does the color shift to compensate? How do the other colors change if the Monored fun police or Big Green Ramp aren’t there?

- What is scarce? The Magic Online Legacy and Vintage Cubes feature plenty of removal, card draw, planeswalkers, fixing, and expensive finishers. But constrain any one of these and the entire format shifts. I’ve noticed that Sniffygull’s Monkey Cube has less cheap interaction than I’d expected and plenty of midrange finishers and shifted my pick orders accordingly.

The next step is to put all of these observations together. If all of these facts are true, what else is likely to be true? If there’s fewer than usual dual lands, then multicolor cards drop down in the pick order or get relegated to monogreen decks. If green has almost no ramp tools and there’s plenty of black removal and white wraths, it’s likely that green is going to struggle and have far too many 3-5 mana creatures. If blue has a lot of support for aggressive UR Wizards and there are zero wraths, then blue-based Planeswalker Control is likely weaker than normal. These are all guesses that will only be confirmed by (repeated) playtesting, but guess enough times and you’ll start to be right a bit more often. You’ll be more likely to draft a strong deck and win, or immediately identify the cool, quirky decks and have a blast.

So, now that you’ve got the gist of how I analyze any cube, let’s focus on the main event: what does JBro’s ETB Cube look like?

The Big ETB Picture

This constraint is pretty hefty—if every creature has an ETB effect (and every spell provides an additional effect), traditional aggro might not work. There just aren’t many one and two mana creatures like Vexing Devil to fill out the lower end of a curve. Moreover, ETB creatures tend to work best in midrange and control strategies that grind out value rather than aggro decks which win before card advantage can take over.

If aggro is awkward, then I wonder how control decks will change. After all, their main predator is likely to stumble. Will fixing and/or card draw be nerfed? If it’s really easy to generate card advantage and there isn’t enough fun police, then the best decks will likely be greedy, multicolor decks that play all the best cards.

We’ve only got one unusual constraint to juggle, so while I could endlessly wonder how each change affects the whole, I’ll keep these first few ideas in mind as I jump into the list.

Live for the Swarm

With Thraben Inspector as white’s sole one-mana creature, white aggro clearly isn’t where I want to plant my flag. The cube smartly leverages white’s high density of blink (and bounce) effects to generate additional value with all its ETB effects. But aside from Sunblast Angel, there aren’t many amazing ETBs that can end the game with a single use or lock it up with repeated use. It seems like white’s strategy is going super wide with tokens and anthems or winning by generating MAXIMUM VALUE with blinking.

White lacks wraths and is fairly light on creature removal. These make sense—if white is so good at generating value, it shouldn’t be super easy for it to impede opponents’ progress or reset the board with a wrath. But those missing effects will have ripple effects on the other colors and be things I’m looking to replace from a secondary color. I also notice that white has a very high number of five drops—again, not a problem, but I expect to deprioritize them when they’re this plentiful.

Blue Who?

Blue is in an interesting spot. On the one hand, it is the color that tends to do best when battlefields are stalled and value is generated, so I’d expect restraint on its many powerful ETB effects. On the other hand, if every color has plenty of access to card advantage, blue might struggle to leverage its greatest strength.

Reviewing the blue creatures, Brostoff exercised excellent restraint. Blue could easily have a pile of three drop Man-o’-Wars to disrupt an opponent or recur its own ETB triggers leading into a bevy of Sphinx of Uthuun-style finishers. Instead, it has small and fragile creatures that will often draw a card (or better) but struggle in combat. It looks like heavy blue decks need to rely on big spells like Treasure Cruise and Hour of Eternity to massively outvalue the opponent, while in less dedicated decks, blue will play a supporting role by smoothing out draws with scry, card draw, and flexible bounce.

Blue’s biggest strength seems to be its many spells that provide dramatic effects. Its biggest weakness is likely its small number of creatures and their small stats. Normally, I’d want to pair those big spells with a pile of wraths to keep the board clear, but we already know that white doesn’t have those. It’s got lifegain to pull games back to parity, but that doesn’t wholesale invalidate an invading army of value-generating attackers.

The Biggest Toolbox

Black’s ETB creatures have given my cube more trouble than any other color’s. There are so many Nekrataals at 3-5 mana and cheap disruptive creatures like Brain Maggot. They overpowered opponents after I dropped the power level by weakening ramp, wraths, and card draw spells. Even before looking at JBro’s black cards, I wondered how many of those powerful troublemakers I’d see and whether black might have a leg up thanks to how many amazing ETB creatures it has.

As soon as I started looking at black’s creatures, I wanted to force black. Black has four two drops that provide a card’s worth of value (via card draw or discard), almost all of its three drops provide a card’s worth of value, and it has an excellent top end with major card advantage providers like Gonti, Lord of Luxury and Noxious Gearhulk. Black also has two easy-to-use wraths in Bontu’s Last Reckoning and Crux of Fate to help it reset against a white player who’s gone too wide. Whip of Erebos also stands out as an incredible value engine that makes the game almost impossible to lose while it’s active.

There’s also good restraint here. Black has far less targeted removal than it does in most cubes. Its spells can’t generate value unless it has creatures in the graveyard, and there aren’t any effortless sacrifice outlets like Viscera Seer or Yahenni, Undying Partisan (which lack ETB effects). I’m expecting black to be very strong, but not so strong that it’s unbeatable or can support half the table drafting it.

A Big Red Question Mark

Red is the color I had the most questions about. In most cubes, red cards can (generally) be sorted into Monored aggro creatures, interaction, and replaceable finishers. If most of the cheap aggressive creatures can’t be included, red’s likely to deviate heavily from its normal strategies. And if spells need to provide additional value, there’ll be far less cheap interaction like Lightning Bolt. I’d wager that there’s token production (possibly with some team buffing) to fill in that gap and red will have unusually strong top end relative to the other colors to offset these handicaps.

Looking over the creatures, red has a variety of ways to accrue value. This is both an advantage, since it can attack from many angles, and a disadvantage, since token production, direct damage, and artifact & land destruction push it in different directions. Red has the almighty Kiki-Jiki, Mirror Breaker (which I know combos with Restoration Angel) and Splinter Twin (which may or may not have an infinite combo)—two very powerful effects that make me wonder just how much fixing there is to enable them.

Red still seems able to play the fun police, but there’s a decent chance I’ll want to avoid it for my first draft. Part of this is just personal preference (I love green-blue goodstuff) and part of it is knowing that many people default to heavy red or Monored when they don’t know a cube. If red’s especially challenging to draft, I’m going to want to avoid being party to any trainwrecking.

Thumbs Up for Green

Green and black tend to have excellent ETB creatures. The main questions on my mind are how good its fixing is (since most colors have heavy color requirements) and how powerful its top end is (there aren’t any Legacy Cube-level finishers like Grave Titan that wholesale invalidate opposing board presence).

Looking over green’s many creatures and relatively few (but powerful spells), it hews closer to my expectations than any other color. Green has plentiful fixing, easy card advantage, and a massive array of expensive threats. Hornet Queen and Garruk Wildspeaker are two of the strongest threats I’ve seen.

Before heading into multicolor, colorless, and (most importantly) lands, I find I’m already wanting to be black-green if possible. When everyone’s trying to grind value and there aren’t a ton of wraths and planeswalkers, there are few better or easier options than Rocking out. This also seems like one of the easier color pairs to make work, thanks to green’s fixing and black not having quite as heavy color requirements as white and red.

All the Colors and None of Them

With only two multicolor cards per color pair and few huge payoffs, it looks like there is indeed a bigger push to be monocolor. That’s unusual in cubes and frankly refreshing—usually multicolor cards are splashable mega-bombs, not a reward for being in a color pair.

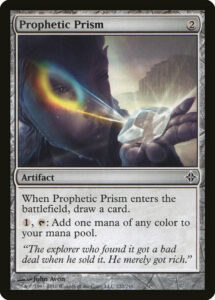

The small number of colorless cards include some extraordinarily powerful cards like Solemn Simulacrum, Myr Battlesphere, and my favorite card, the uber mana-fixer Prophetic Prism. I expect to draft many of these cards highly, since many of them are comparably strong to most colored cards and they forestall my need to commit.

The Piece That Had to be Missing

The biggest question I have about any cube is its fixing. Strong fixing enables greedy decks, mitigates the inherent downside of multicolor cards, and can lead to degenerate formats where everyone fights for multicolor goodstuff (while dying to the one person playing the fun police). Weak fixing leads to awkward decks, where only one or two players can get greedy and many players have two color decks with major color issues.

Given my concerns about control decks being too good, I expected Brostoff to be restrained in his fixing—but wow. Ten guildgates, Evolving Wilds, Thawing Glaciers, and Ancient Ziggurat. That’s it. Even if you take every colorless fixer you see, you need to be playing blue or green to get away with anything other than a (mostly) monocolor deck. This design choice, more than any other, likely defines how the cube functions. You can’t afford to play all the best cards because there’s no way you’ll cast 70% of them. There might not be a streamlined fun police to prey upon slow control decks, but those decks can’t stretch their colors without getting run over by three creatures in a row.

I think I get it: the cube is defined by midrange decks vying for dominance. There are almost no haymakers that immediately end the game, so it’s all a matter of leveraging small advantages until you eventually grind your opponent into submission (or they stumble too hard). Wow! That’s an end result I’ve seen before, but a completely different method of getting there.

That’s how far I got in ten minutes of perusing the cube list (and hours of documenting the process). Hopefully you enjoyed this look into how I evaluate cubes. It’d be nice if this work pays off tonight and I can draft something stellar, but I’ll be just as happy if I’m completely off base and learn from the experience. After all, cube is awesome.

And, as always, thanks for reading.

Zachary Barash is a New York City-based game designer and the commissioner of Team Draft League. He designs for Kingdom Death: Monster, has a Game Design MFA from the NYU Game Center, and does freelance game design. When the stars align, he streams Magic (but the stars align way less often than he’d like).