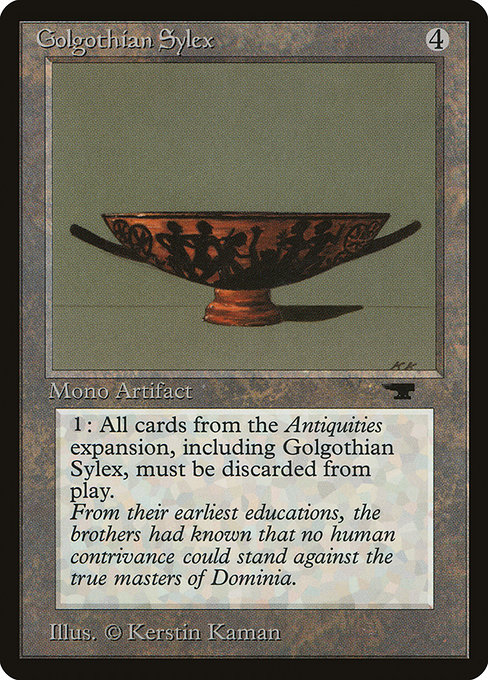

One of my favorite ancient stories is Plato’s Symposium, sometimes called the Symposium on Love. In the story, Socrates strolls into an evening gathering of friends, who begin to have something of a philosophical game, where they take turns discoursing on the origin and nature of love. While they are doing this, they pass a massive drinking vessel—called a kylix (κύλιξ)—full of wine, from person to person, and grow progressively more inebriated. If you’ve played magic for awhile, you’ve probably seen them before on such cards as Mana Cylix, Ashnod’s Cylix, and this beauty:

Golgothian Sylex has no pretense about being anything other than an ancient Hellenistic wine bowl, but it has single-handedly inspired this article for reasons that will become clear momentarily.

While Antiquities might be said to be the start of Magic’s own narrative lore, a story told through the cards for the very first time, this card and others still borrow very much from real world mythologies. “Golgothian” is a very particular reference—Jeff Grubb’s novel, The Brothers’ War, explains this as referring to Golgoth, a name with unclear origins lost to time. It seems likely to me, however, that this comes from the very non-Dominarian word “Golgotha”(which means “The Place of the Skull”), the name for the hill upon which Jesus of Nazareth is reported to have been crucified. Thus, Golgothian Sylex (or Cylix/Kylix, as it ought to have been) is another way of saying the “cup of/from Golgotha.”

There are two primary layers of meaning that came to mind when I realized this some months ago—aside from the possibility that the designers just thought the name sounded cool. The first is that this Sylex refers to a cup referred to in the Christian scriptures. Cups are a common metaphor in the Jewish and Christian scriptures. Jesus refers to the cup he “must drink” (Matthew 20:22; John 18:11), but that he wishes “would pass from” him (Matthew 26:39). Later, on Golgotha, John’s gospel recounts that Jesus was given sour wine, mixed with hyssop, from a bowl via a sponge on a pole. The Catholic Biblical scholar Brant Pitre has proposed that this last bitter drink is the symbolic final cup of Jesus’s Passover meal with his disciples, linking his own death with the Passover, a feast remembering the final plague wrought by God on the Egyptians: the death of the firstborn.

If this is the reference here, the Sylex recalls the suffering and death of Jesus, and also the deaths of the ancient oppressors’ firstborn children. The Sylex’s “wrath” effect, depicted in more detail on Urza’s Ruinous Blast, plays well with the connotation of suffering and the flavor text is evocative of power beyond human imagining. For a theologian like me, this interpretation works, but I like it even more if we push this idea of “the cup at Golgotha” further. Reader, we may have found Magic’s original Holy Grail.

The Legend of the Holy Grail

For those who may be unfamiliar, the Holy Grail is a liminal object that comes to prominence in the various myths and legends surrounding the fabled King Arthur. According to Robert de Boron’s Joseph d’Arimathie composed between 1191 and 1202, it was used by Jesus Christ during the Last Supper (his final Passover) in Joseph of Arimathea’s upper room, and Joseph of Arimathea is said to have used the same kylix to collect the the blood and water that spill from Christ’s side at the crucifixion on Golgotha. Because he was a tin trader (so the story goes), Joseph of Arimathea made periodic trips to Cornwall in England (one of which inspires William Blake’s famous “Jerusalem”), where he ultimately resides with the grail at or near Glastonbury Tor.

Allusions to the Grail Legend are made throughout Magic’s history, from the recent depiction of the Grail as a cauldron in the Throne of Eldraine to the long list of chalices, cups, cylices, and a more direct allusion in Sol Grail. While having no flavor text of its own, Throne of Eldraine’s The Cauldron of Eternity is described in the set’s accompanying book, The Wildered Quest. In a short passage, the long cursed planeswalker Garruk finds himself healed by the lost artifact of the Kingdom of Locthwain. The brevity of this encounter is absolutely stunning: rather than the object of a quest, Will Kenrith’s altruistic perseverance for Garruk’s sake causes the Cauldron to appear and save them both; a Deus ex Machina purifying Garruk of his curse, and putting them back on the road to finding Oko and saving their father the King.

My interpretation here owes much to grail scholarship that links Celtic myths involving cauldrons to later (allegedly) Christianized stories that give the grail its Judean provenance. Whether or not these theories about the pagan origins of the grail legend are correct will likely always remain a contested question, but I wanted to highlight this example to introduce my next point: most chalices, cylices, and grails in Magic’s history involve life, death, knowledge, and power; their game mechanics also suggest that one might drink from them. Indeed, in filmic versions of grail stories, like Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, drinking from the grail heals wounds, and its presence alone can grant immortality. This kind of representation moves the grail into the realm of a kind of “communion chalice,” which conveys spiritual life on the communicant.

As I mentioned in last fortnight’s essay, this sacred Christian ritual is imitated by the vampiric clerics on Ixalan, whose Hierophant’s Chalice brings life-giving blood to the lips of the aristocratic Church of Dusk. In the medieval Grail legends, however, the cup is not often drunk from, but functions more like a religious relic. It’s a mystical, almost living object, to be encountered, looked upon, and venerated akin to the bones of saints that are enshrined in churches. In this way, the grails of Magic cleave more closely to popular media than medieval myth.

Golgothian Sylex is an interesting exception, responsible rather for the powerful blast that purged Dominia of the Phyrexian threat, an extreme purification of Phyrexia from the planet. While the likeness to a nuclear blast might not hold, certainly the Grail’s power is that of purification. Much like The Cauldron of Eternity, in Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, one’s purity determines whether one can even see the grail. When Sir Bors, Sir Perceval, and Sir Galahad see it, each only see it to the degree that they are pure of heart. Bors sees only light, and subsequently takes monastic vows. Perceval sees it, and dies soon after. Galahad the Pure sees the grail as it is, and dies immediately, alluding to the power of the face of God in Exodus 33:20, “You cannot see my face; for no one shall see me and live.”

Thus, just as with Magic’s numerous allusive chalices, the Grail is consistently connected to the mysteries of life and death. In de Boron’s telling, the cup is created as a holy relic in Christ’s death moment, and serves to preserve Joseph of Arimathea’s life until he can bring it to England. In later tales, it is said to reside in the Land of Eternity, or The Undying Lands, and offers a kind of Vita Ex Morte—the kind of death that Perceval and Galahad receive is a death to eternal life. This power is so evocative that in recent years, Glastonbury Tor, famed for its role in the story of Joseph of Aramathea and as a possible site for the “Isle of Avalon”—the final resting place of King Arthur in Geoffrey of Monmouth and Malory—has been thought of as a possible gateway to the land of the dead or the Otherworld (Annwn), a fitting final resting place of the Grail.

Karn and the Hero’s Journey

Understanding the Golgothian Sylex as a stand in for the Holy Grail on Dominaria presents us with some interesting possibilities for interpretation. As regards the Sylex, the official lore is murky, as is often the case when new Magic: The Gathering sets seek to make use of old material. What will become and remain canon is still an open question, but as it stands, I’m willing to speculate that the journey of Karn (like the journey of so many of Magic’s heroes) can be compellingly recounted as an archetypal hero’s journey; especially insofar as Karn’s quest for the Sylex (provided it’s the same or at least a very similar sylex) during the events of Dominaria can be seen as a chapter in Magic’s own Grail legend.

Karn’s arc from Scars of Mirrodin to Dominaria corresponds eerily closely to the latter part of Campbell’s notion of the “Initiation” mytheme, found in his Hero with a Thousand Faces, which he subdivides into “Atonement (Abyss),” “Apotheosis,” and “the Ultimate Boon.” Karn’s retreat to what becomes New Phyrexia is figurative descent into the Abyss, or Hell, especially given the flavor Phyrexia’s creator, Skaff Elias, envisioned for it when he was working on Antiquities, “I definitely thought of the Phyrexians . . . I can remember the flavor text where the guy opens the gate and [experiences] the smell of ruby dust and the oil rain on his face. . . . It’s kinda cool that they could go to hell, their own special hell.”

Karn’s retreat to what his Creation has become is a kind of atonement, where he hopes to protect others in the multiverse from the Phyrexian corruption that is taking hold of him and his world. There, in the abyssal core of New Phyrexia, the planeswalker Venser saves Karn by giving him his spark, purifying him. Karn’s triumphant apotheosis can be seen on Karn Liberated. Reborn, in a matter of speaking, now Karn seeks and acquires the “ultimate boon,” the holy grail—the Sylex—which he hopes to use against the Phyrexians much as his own creator, Urza, did to end the Brothers’ War.

The completion of Karn’s arc, as we’ve seen in the epilogue to War of the Spark, points toward the return to New Phyrexia with the “elixir” to cure the world’s ills. This is almost a recapitulation of stories like (but not limited to) the Christian “harrowing of hell,” in which the imprisoned are freed by the one that cannot be held. For Karn, Scion of Urza, this represents the possibility of a kind of closure to an arc that has thus far been a decade in the telling, and a poetic echo of his own creator’s use of the same (or a similar) device.

The Truth of the Grail

Near the end of his own video on the subject of the Grail legend, Mike Rugnetta reminds us that stories of quests like these are often intertwined with and convey particular religious and cultural values. For folks like Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell, this archetypal quest is a metaphor for any journey toward understanding ourselves and the world. In the traditional Grail Legends involving King Arthur’s knights Perceval and Galahad, the quest is about uncovering the meaning of the Grail; for Perceval, it is the answer to a “healing question” he should have asked the Grail’s guardian, the Maimed King, which would restore health to the king and fecundity to his lands.

French philosopher and mystic Simone Weil recounts this question as “Quel est ton tourment (What are you going through)?” This attention to another’s affliction, the “plenitude of loving one’s neighbor,” she writes, must be asked before the Grail can be found (resonant with the Cauldron in The Wildered Quest). Even if we reject my hypothesis that the Golgothian Sylex is meant to be a stand-in for the holy grail, we still find Karn in a kind of Quest for the Holy Relic-like scenario: Karn sought Urza’s Sylex and Sir Perceval sought the Grail as a way to purify a corrupted world, and along the way must also find themselves purified.

In a way, this isn’t surprising. Campbell claims that “myths aren’t really written by their authors. Instead, they are manifestations of universal cosmic forces that shape the human subconsciousness. (Rugnetta)” Thus, whether intentionally alluding to the Grail narrative or not, Karn’s narrative follows these beats because the story structure they hold in common is so powerful. The Hero’s Journey isn’t over for Karn, but he’s turned his attention to the afflicted and entered into solidarity with them. What if Jung, Campbell, and Rugnetta are correct, and these stories are archetypal metaphors for our own individual journeys toward fulfillment? It may be worth asking ourselves whether and how we’ve done the same.

Recommended Media:

Sergei Bulgakov, The Holy Grail and the Eucharist (Library of Russian Philosophy)

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces

Mark Rosewater & Skaff Elias, “Drive to Work ep. 750”

Stephen King, The Dark Tower series

David Russell Mosely, Letters from the Edge of Elfland (relevant posts)

Mike Rugnetta, Crash Course Mythology #28, “Galahad, Perceval, and the Holy Grail”

Martha Wells, “Return to Dominaria: Episode 9”

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.