As I suggested near the beginning of my last essay, sometimes a Magic card can be more than a game piece, more than a mere glimpse into a fantastic, fictional world: art, flavor text, and function can combine to convey messages that designers may or may not have ever intended but that nevertheless say something meaningful.

Earlier this year, the reprinting of Idyllic Tutor impelled my work on this series of essays, and current events being as they are has prompted me to explore this particular card more deeply. This is in some ways an awkward article to write, because in a very real way, I expect that the flavor text I’m about to fixate on is far from what many of us may be feeling right now. In another way, this is precisely the reason to commit these words to the page:

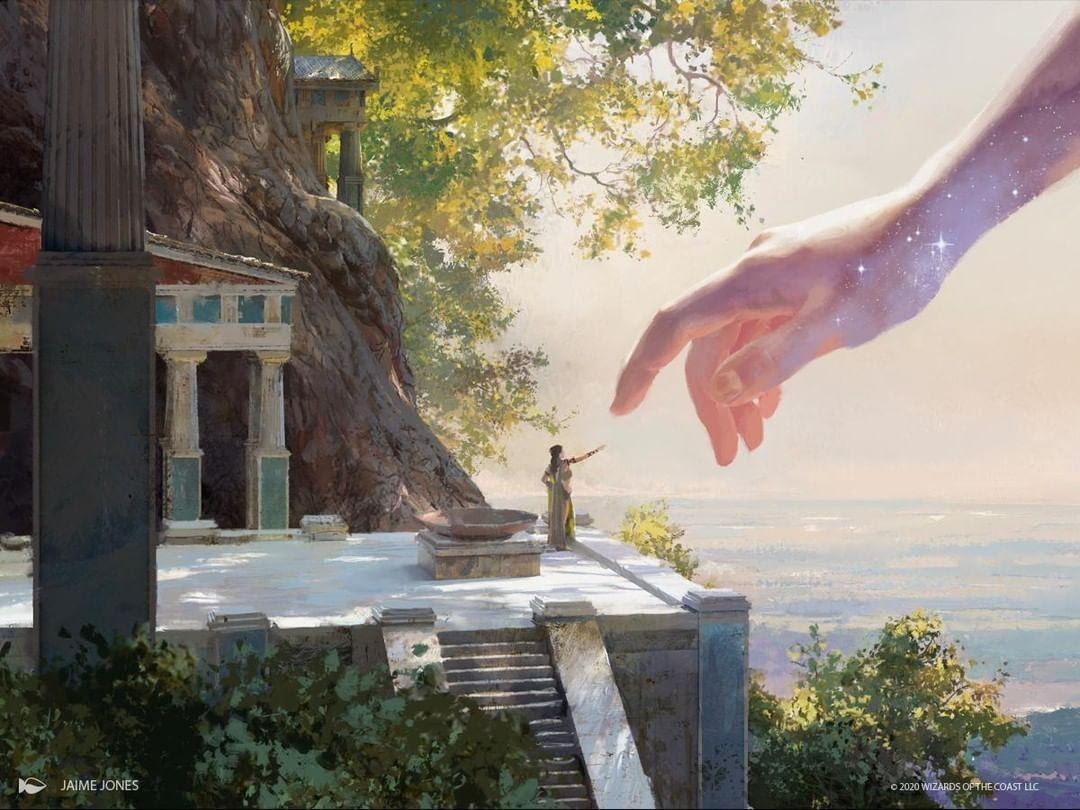

Idyllic Tutor, by Jaime Jones.

“You are loved, child.”

In its flavor text, taken from Ken Troop’s short story, “Seasons in Setessa,” the newest printing of Idyllic Tutor in Theros Beyond Death uses this quote from Karametra, God of Harvests to invite the viewer to contemplate the relationship between the human and the divine, between people’s inner lives and their outer struggles. Therosian gods rely on the devotion of mortals, but on this card and in Troop’s short story, Karametra assures the Setessans of her love.

What can this mean in the context of this card, and for those who study under an idyllic tutor? Can we also find meaning in Karametra’s assurances?

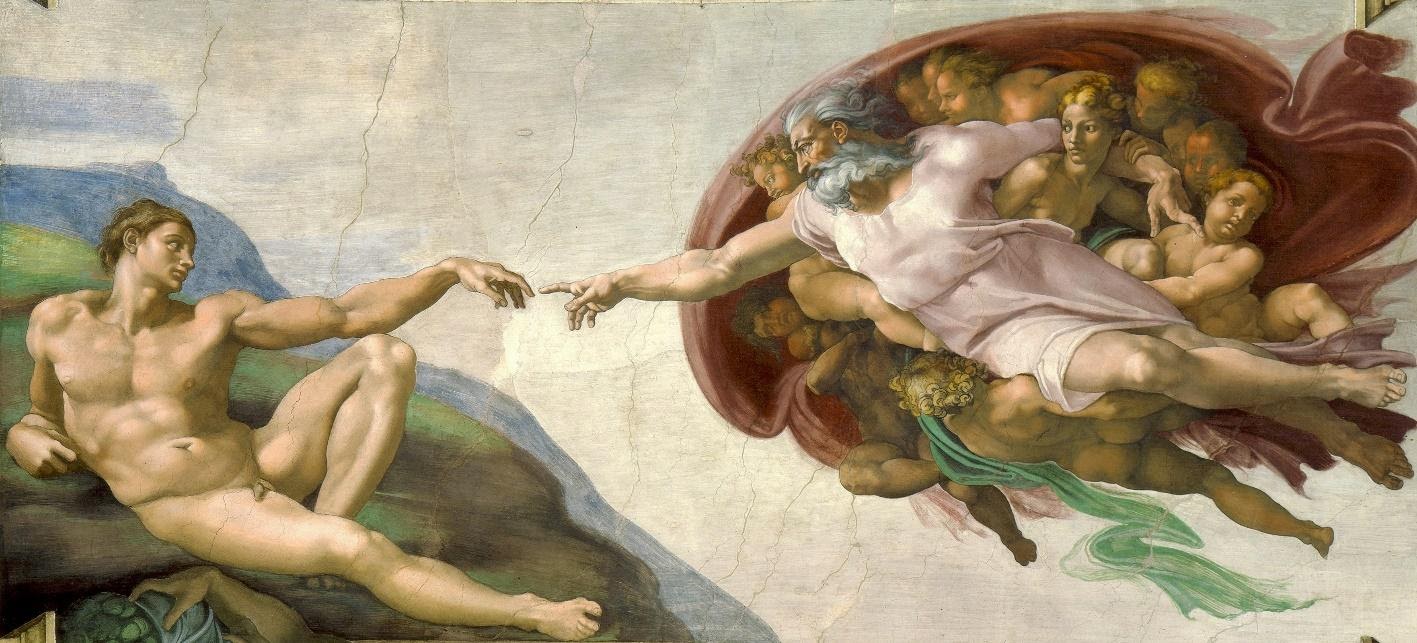

The Creation of Adam, by Michelangelo; Sistine Chapel, Vatican City.

Renaissance References:

In Jaime Jones’s painting, the starry hand of Karametra is massive, reaching down toward the outstretched arm of a priestess or oracle, who stands at the entrance of a seaside temple, built into the trunk of a massive tree. Jones’s art references Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam, which features the (human-sized) right hand of God reaching over to almost touch the finger of Adam, who reclines upon the same earth from which he was made mere moments ago. This religious juxtaposition is provocative: on Theros, the beliefs of mortals created the gods as mortals imagined they ought to be—massive, powerful, and seemingly distant in the starry heavens above.

Michelangelo’s Catholic imagination envisions the words of Genesis more literally, as Adam is fashioned “in the image and likeness” of the Creator, who will walk “in the cool of the evening” through the same garden as the first pair of humans. Theros’s gods are “dreamed into being” through the fervor and belief of mortals, where later Christian thinkers have asserted that the Abrahamic God not only sculpted or spoke to create the world, but (as some Christian theologians have put it) “loved [it] into being.”

In both cases, what is believed and what is loved become real through the sheer act of believing and loving, so much so that the dreamer and the dreamed, the lover and the beloved can relate to one another as two distinct persons. In Theros, furthermore, we assume now that the devotion of mortals is so great, that a god like Karametra can love her followers. She can reveal things to them that they themselves were not aware of, except maybe in the deepest recesses of their souls. What is it, then, that our idyllic tutor teaches?

Idyllic means peaceful, happy, or “like an idyll”—that is, reminiscent of an eidullion, a short poem of pastoral subject matter. The reference to ancient Greek poetry about gods interacting with mortals even in the simplicity of rural life certainly makes sense and is especially poignant on this iteration of the card: Karametra, being based on Demeter (the ancient Greek goddess of agriculture and fertility) and Hestia (goddess of the hearth and home), is a goddess that privileges the rhythms of rural and domestic life.

According to the Homeric hymns, it is Demeter’s sadness at her daughter’s four-month visits to the Underworld that causes the changing of the seasons, and the natural rhythm of planting and harvesting that follows with them. This connection to pastoral, agricultural life needn’t exhaust our reading of “idyllic,” however: it is also possible that that this tutor teaches her followers the ways of peace and happiness. Perhaps in the acceptance of the toils of agricultural and maternal labors, which now bear fruit only after time and travail.

Idyllic Tutor, by Howard Lyon.

This interpretation is supported if we look back to another version of Idyllic Tutor, from Morningtide. Howard Lyon’s original art for this card features a dove bearing a golden thread, evocative of doves in Western, especially Christian, visual culture, which often bear olive branches: symbols of peace. In addition to being a symbol of peace, the dove represents the Holy Spirit, which descends upon Jesus like or as a dove at the start of the gospels of Matthew, Luke, and John as an indication of divine approval. Late in the gospel of John, Jesus promises to send this same spirit as an advocate and bringer of peace and consolation:

…But the Advocate, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you everything, and remind you of all that I have said to you. Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you […] Do not let your hearts be troubled, and do not let them be afraid. (John 14:26-27 [edited] [NRSV])

In the centuries that followed, Christians would identify the Holy Spirit as the love between the other two members of the Trinity.

Coincidentally, there’s a deeper religious resonance between the art of Lyon and the art of Jones, that almost makes me wonder if this was intentional. Both pieces can actually be said to reference the Holy Spirit, as in the ancient Latin hymn, “Veni Creator Spiritus,” which says, “Dextrae Dei tu Digitus…Infunde Amorem Cordibus”—“You are the finger of God’s right hand… pour love into our hearts.” Karametra’s extended right hand stands in for the representation of the Abrahamic Creator God in Jones’s idyllic reference to The Creation of Adam, just as a golden thread is brought to the caster by a dove reminiscent of so much historical Christian art.

Indeed, it’s certainly possible that Karametra—coming into being from the dreams, imaginings, and longings of her mortal followers—loves her followers precisely because she is the manifestation in the stars of their own longings to give and receive love in all its fecundity. The oft-repeated line from the Bible, “God is love,” has been fundamental for Christian religious thought. The ideals of love were also symbolized by doves in ancient cults of the Greek goddess Aphrodite, the Canaanite goddess Asherah, and the Sumerian goddess Ishtar—all goddesses whose areas of influence included love, to a greater or lesser extent.

Holy Spirit Window, by Bernini, St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City.

Lyon’s dove, however, does not carry an olive branch. Rather, it bears in its beak a golden thread, symbolizing an idea or characteristic that runs throughout all of something, connecting or binding the parts together, and revealing its value. New Age mystical writers often speak of how becoming spiritually aware can help one to find the golden thread in one’s own life, or throughout all reality, discerning how everything is connected. In Lyon’s painting, the idyllic dove brings the “golden thread” to mind, just as the flavor text from the Book of Kith and Kin suggests:

If one’s life is blessed, solutions to all life’s problems will appear at the right moment.—The Book of Kith and Kin.

Thus, the idyllic tutor is not simply peaceful, but a symbol of and messenger of peace of love, who seeks to—“at the right moment”—reveal to the caster that “golden thread,” the enchantment that will bind everything together.

Enlightened Tutor, by Howard Lyon.

Continuing Education

Lyon’s “Idyllic Tutor” is referenced again on the Eternal Masters reprinting of Enlightened Tutor—as he told Michael Paul Skipper at Puca Trade, the reference “was my idea… I submitted that and I said, ‘Hey, these are both tutor cards. Would it be alright if I put the dove on the book?’” Lyon is known for thematic continuity in a number of his pieces that in themselves tell a story—often up to us to interpret. Here, the Enlightened Tutor reaches up for a book—maybe the Book of Kith and Kin—that is covered with the focus of Idyllic Tutor’s card art: the dove and the thread. The enlightened tutor follows in the spirit of the idyllic tutor, either compiling or studying its wisdom, having it at the ready for others.

In white, being tutored appears to us often as a kind of spiritual education—and one with a character that matches the flavor of white’s color identity from the beginning (more on this in a future piece). An idyllic tutor needn’t only be a messenger of peace and love, or an irenic lover; she may also be a teacher of the patterns of pastoral existence, of planting and harvest, a divine midwife of mortal wisdom, or the spiritual seamstress who brings to our attention the golden thread running through the tapestry of the real. She might also teach us, as in the lyrics of the classic song “Nature Boy”:

The greatest thing you’ll ever learn

Is just to love and be loved in return.

In short, the Idyllic Tutor represents some of the best that the color white has to offer. Despite being mono-colored and referencing peace and plains in its name, it remains open-armed to other colors: in wisdom, it its open to blue; in love, it’s open to red; in the rhythms of the natural world, to green; and when that cycle passes through death, to black. While other white cards might warn us about the propensity for institutions to become oppressive, or to enforce order at any cost—a familiar theme these days—this one, at least, represents in some ways the “better angels” of white’s nature.

It is here that we can find something philosophically valuable that spills over into life outside the world of the game—with the caveat that given the events of this past spring and summer, this will perhaps sound like I’m being too optimistic, or naively hopeful. Howard Lyon, himself a man of faith, has been quoted as saying “I hope that who I am, which is very much shaped by the gospel, comes out in my work… I try to create art that uplifts, either through beauty or the message being shared.” Whether we’re scholars or practitioners of ancient religious traditions or even those same traditions’ most ardent critics; I think that what is represented here, in these cards, is an uplifting thought, and could stand to be more represented, whatever the means or the medium: messages of love, peace, encouragement, assurance, and consolation.

Magic is full of these messages, of course, and not only in the art or the flavor text of cards. As many creators and youtube personalities say, Magic is about the Gathering. Our games with one another are events of community—even virtual games, if we aren’t fortunate enough to have someone else in our household to play with face-to-face. Nevertheless, in the wake of recent attention to ways in which Magic has failed large sections (and by failing them, failed all) of its player base and how Wizards has failed members of its staff, it’s fair to look elsewhere, as well.

Reassurances become hollow if we don’t follow through and practice what we preach, and no amount of evocative art and flavor text can be a substitute for real action. We can choose, however, to use our words and actions to uplift, and to make the words of a fictional Therosian deity, “You are loved,” real for others in our community. Until next time.

For further reading:

The Homeric Hymns (Penguin Classics Edition).

The Idylls of Theocritus (Oxford Classics Edition).

Bernini: His Life and His Rome, by Franco Mormando (University of Chicago Press).

Michelangelo: The Artist, the Man, and his Times, by William E. Wallace (Cambridge University Press).

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.