This past weekend, I had the pleasure or playing Derek Gallen‘s updated cube and meeting Urchin Colley (it’s too rare for us Hipsters to see each other, especially now that so many folks don’t live in Brooklyn). Derek’s cube is my kind of cube, with a lower power level than a Legacy Cube while still feeling strong, a bunch of less usual inclusions (like our titular card), and a ton of thought about its continuous creation (Derek and I have spoken at length about cube design).

In this draft, I got to play with a card I’ve read plenty of times, but never actually had the chance to try out: Truth or Tale. Today, we’ll dive into this not-so-simple card with a rich history.

Divvying it Up

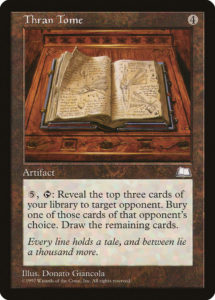

Truth or Tale is a clear callback to one of the most powerful and iconic card draw spells in all of Magic, 2000’s Fact or Fiction. But Fact or Fiction is actually one of six Invasion cards that introduced the “divvy” mechanic, where one player splits cards into separate piles and the other chooses one of those piles. Divvying has been used sparingly throughout Magic, appearing a grand total of 18 times. That’s few enough cards that we can list all of them, divvying them up by category.

Fact or Fiction variants

1. Phyrexian Portal (yes, the first FoF predates it by four years)

2. Fact or Fiction

3. Truth or Tale (one of the only FoFs not to put unchosen cards in the graveyard)

4. Brilliant Ultimatum (FoF but it’s a million mana and you cast them for free)

5. Sphinx of Uthuun

6. Jace, Architect of Thought (the first smaller FoF)

7. Steam Augury

8. Epiphany at the Drownyard

9. Fortune’s Favor (the first hidden information FoF)

10. Unesh, Criosphinx Sovereign

11. Atris, Oracle of Half-Truths

Gain a non-card thing of your choice

12. Death or Glory

13. Boneyard Parley

Lose things of your choice

14. Bend or Break

15. Do or Die

16. Liliana of the Veil

Restriction of your choice

17. Fight or Flight

18. Stand or Fall

There’s also honorable mention, Whims of the Fates, the card that almost broke Magic Online, involves three piles, offers no choice beyond the creation of piles, and is symmetrical—everyone plays, and everyone suffers. There’s also cards like Murmurs from Beyond that involve making piles, but no choice from the other player.

It’s worth noting the differences in how these piles are constructed. Fact or Fiction is stronger and harder to resolve than Steam Augury, since it guarantees you get the card you want from your top five and forces your opponent to make choices with very limited information. On the other hand, Steam Augury presents your opponent with information about what you value and denies you the certainty of getting the specific card you want. Atris, Oracle of Half-Truths provides a much easier to resolve twist on Fortune’s Favor, since your opponent knows they’ll basically always do a 2-1 split, rather than have to decide whether to go for 2-2 or 3-1.

To draw some general principles from these examples, it’s faster to split smaller piles than larger ones, there’s a big shift in power and frustration depending on who splits the piles and who chooses, and there’s quite a lot of ways to construct card-draw piles while it’s harder to design other divvy effects without incredibly dramatic effects.

Making the Choice

I planned on leaving Truth or Tale in my sideboard, since it’s a fairly weak cantrip. However, I needed a bit more card smoothing and frankly had never had the opportunity to cast it. So I tossed it in, assuming it’d be about on par with Anticipate—it sees more cards than Impulse, but I’m both not guaranteed the card I want from among the options and it shows my opponent a lot of what I’m up to. When I finally put it on the stack, I realized there were probably only two kinds of piles I’d want to construct: if I need lands, I split up the lands among a 3-2 split (and probably put the best nonland card in the pile with the land I need less). If I don’t need lands, I probably do a 4-1 split, where my opponent either gives me what I (potentially) want most or an Impulse.

It was frankly charming seeing how much easier the card was to resolve than I expected it to be. No hemming or hawwing about exactly how I should make each pile. Perhaps I wasn’t overthinking the challenge enough, but ease of overthinking is probably why we see so little divvying these days.

Choosing when, what, and how

Divvy cards are a great example of potent seasoning in game design. A little bit of them can go a long way in creating cool moments of tension, and more than a restrained amount can be overpowering. We don’t see cards like Truth or Tale anymore because they involve so many more steps than Anticipate, but for fairly minimal gain. Imagine a world with a one mana Truth or Tale that revealed the top three cards. Even if it’s worse than Opt, people would play it and you’d have to spend a couple minutes most matches waiting for one player to sort their piles while the other tries interpret whether the single card pile was indeed the most desirable one or just the bait.

Divvy effects are prone to overthinking, and bet that’s why they’re embracing hidden information (Fortune’s Favor), smaller piles (Jace, Architect of Thought), or a hefty mana cost (Unesh, Criosphinx Sovereign)—to make them quick or infrequent tense moments rather than frequent ones that bog games down with mini-choices. I appreciate that Wizards is experimenting more with divvying cards and also the restraint with which they’re doing so. And that’s all I’ve got to say about Truth or Tale.

—Zachary Barash is a New York City-based game designer and the commissioner of Team Draft League. He designs for Kingdom Death: Monster, has a Game Design MFA from the NYU Game Center, and does freelance game design. When the stars align, he streams Magic (but the stars align way less often than he’d like).