“This product is not for you,” is a phrase with nuance. It’s vital to understanding and appreciating Magic, and can be applied to many things in life. It’s a phrase you might see on Blogatog as Mark Rosewater patiently responds to a less-than-calm fan. Are they unhappy because a product doesn’t meet their standards, or because product wasn’t intended for them in the first place?

This phrase is also indicative of a major issue Magic may need to tackle going into 2020. We’ll get to that in a moment. But first, what does it mean?

One Product For Many

Magic’s greatest strength is that it is not one game. Magic is a system of games, each using the same game components: cards and a (mostly shared) ruleset. Within the game system of Magic, you can play Commander, Draft, Standard, Pioneer, Pauper, Modern, Legacy, Vintage, Planechase, Emperor, Two-Headed Giant, Canadian Highlander, Archenemy, Old School, Face the Hydra, Explorers of Ixalans, Ravnica block Constructed Star, and a variety of other formats—many of which were created by players, not Wizards of the Coast. But there’s more. Magic generates and enables activities surrounding Magic that don’t even involve playing Magic, such as: deckbuilding, collecting, trading, following the story, cosplaying, buying original artwork, analyzing metagames, and creating content like this article you are reading. We also have Tarkir Dragonfury and Dungeons & Dragons campaigns set in Magic’s multiverse.

The aforementioned are just a fraction of ways that people engage with Magic. Fans of these different formats and activites have different, sometimes contradictory needs. For instance, Commander players benefit from more creatures being legendary while other Constructed players benefit from the reverse. But there are more audiences: Limited players have less of a horse in the race, but collectors of legendary creatures are invested in having more cards to chase, and lore-loving players either appreciate having more characters to dream about or lament more characters that the story doesn’t have room to cover.

This is the tension inherent in everything Magic produces. Magic can only release a certain number of products per year and has dozens of audiences to satisfy, so it has to choose when to target specific demographics of players (e.g. Commander releases, Mythic Edition, Welcome Decks) and when to hit a broader range of groups (Throne of Eldraine, Core 2020). It is human nature to see oneself as the center of the universe (you only ever have direct access to your own life experiences) and so expect everything to be designed for oneself. We are therefore naturally disappointed when a product fails to satisfy us (even when it wasn’t meant for us to purchase). This is the intended meaning of “This product is not for you.” It is recognizing that other audiences exist, that other tastes exist, and that Magic is bigger than any one of its audiences. It is not intended to dismiss criticism across the board, but to disarm criticism when individual expectations miss the intended audience.

However, sometimes a product that is designed for you fails to meet expectations. This happened perhaps most dramatically in four cards being banned from Standard over the past month, and absolutely warrants constructive criticism and feedback. There is also the most painful case of “This product is not for you,” where a product that once was designed for you ceases to be.

2019: The Year of Unbridled Growth

2019 is perhaps the most expansive year for Magic since its creation. It was the year of the MPL, the Mythic Invitational, of Magic-as-eSport, of Twitch Rivals, of MTG Arena’s official release, and the year where Magic had perhaps the most visibly diverse coalition of players. It is the year of Brawl preconstructed decks, Collector’s Boosters, Project Booster Fun, of Pioneer and Mystery Boosters; it is also the year of four Standard bannings, the year of War of the Spark and War of the Spark: Forsaken, and the year that GP Coverage was all-but-cancelled. A year of high highs and low lows, of experimentation and new product lines.

Growth is not merely a good thing—it’s a necessity. If a product or brand isn’t growing, it’s stagnating. Magic’s entire business model hinges on visiting and revisiting settings across a variety of booster and preconstructed products, year after year. Magic is constantly juggling its existing audiences while trying to expand into new ones. However, there is a fear that in 2019, Magic has grown too far, too fast. A fear that in trying to please too many new audiences and shift business models, quality has lapsed and audiences have been left behind. Let’s start with perhaps the most dramatic example.

Sad Vorthos

Greg Weisman’s first War of the Spark novel had the odds stacked against it. It was the culmination of a plotline begun in 2015 by Magic’s in-house team which had to be completed by an external author. Due to some behind-the-scenes mishap, the preceding novel supposed to set the stage didn’t arrive until after the book released, making it so Weisman had to pick up plot threads last seen in 2017’s Hour of Devastation. I didn’t particularly enjoy the book, but there seemed ample reason to downplay its shortcomings.

Then his second book came out. With almost none of the burdens inherent to its predecessor, Forsaken managed to be so problematic that Wizards apologized for its most glaring issue—but allegedly not to readers in China and Russia, which, if true, is a fairly hefty compounding of this problem. This isn’t the start of story problems, though. It’s merely the mess we’ve arrived in.

To avoid assuming that I speak for all audiences, I’ll speak here in personal terms. I am a Vorthos. I love following Magic’s story. Knowing details about its planes and characters enhances my enjoyment of the game. I consider the formation of the Gatewatch among Magic’s best storytelling decisions ever, since it added developing interpersonal relationships to a game that hadn’t featured recurring characters since the Weatherlight Saga ended in 2001. This led to the highest awareness of the story ever.

My enjoyment of the Gatewatch storyline wasn’t always high (and it certainly constricted Planeswalker diversity in Standard early on), but I devoured everything the Creative team created. Alison Luhrs’s rehabilitation and development of Jace and Vraska on Ixalan is my favorite story Magic has ever told, keeping me engaged through one of the rockiest periods of Limited and Standard. Kate Elliott’s Chronicle of Bolas was outstanding, adding depth to Ugin and Bolas, two characters mostly defined by as being powerful, vague, and inscrutable.

However, those two stories are the only stories I’ve loved for the past two years. Nicky Drayden’s slice-of-life stories weren’t for me (though I’d probably love them if played Magic D&D). Both the Dominaria and Vivien Reid stories fell far short of what I’d come to expect. I enjoyed Kate Elliott’s The Wildered Quest and Brandon Sanderon’s Children of the Nameless, but neither satisfied the hunger for ongoing storyline that the Gatewatch had kindled. By the time that War of the Spark: Forsaken released, I’d had enough disappointment that I waited for Levi Byrne’s excellent review and skipped my purchase.

Perhaps Magic’s story “is not meant for me” anymore? Perhaps the kinds of stories I most enjoy don’t have as widespread appeal as I’d like or require too many resources relative to one-off stories. It’s disappointing that I may no longer be satisfied as a Vorthos, but Magic holds more for me than that. After all, I loved Magic when I returned to it in 2010, and that was the era where Magic’s outsourced novels by Robert Wintermute were so bad that Magic either ignored them (The Quest for Karn) or retconned large sections (In the Teeth of Akoum). Perhaps I’m wrong and I’m still supposed to enjoy Magic’s stories, but I don’t expect anything to change quickly or perhaps in the next few years. Consequently, I’ll need to find more enjoyment in the non-lore aspects of Magic (or other media).

Of course, this leads to a bigger fear: what happens if Magic starts to shifts its attention from one core audience to another? What happens if Magic as an entire product line swings away from being a product for you?

2020: The Year the Core Demographic changed?

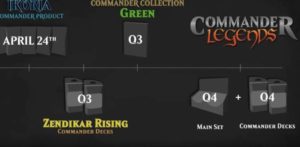

Big changes are coming in 2020. As suggested on Blogatog, Commander might have surpassed Standard and become the biggest Constructed format. As a likely consequence of this data, a Commander product will accompany every 2020 expansion. These replace a Planeswalker Deck and take up the 2020 innovation product slot.

Commander’s current status is the culmination of years of its success shifting Magic’s business model: 2011’s flagship Commander product spawned an annual product line. Iconic Masters and Masters 25 featured far more Commander-focused reprints and fewer Modern or Legacy reprints than any previous Masters set. There’s even been an increasing willingness to print powerful legends at uncommon in expansions, allowing for more legendary cards per set and warping Limited environments around cards like Syr Konrad, the Grim and Chandra, Novice Pyromancer. Magic is increasingly embracing Commander players, and for good reason: they may have become Magic’s biggest audience.

Ever since Standard became the primary format for competitive Magic, taking the title from Type 2, it has defined Magic’s core audiences. Like it or leave it, Standard is essential for Magic’s business model. Without healthy demand for cards in every new booster product, it’s hard to justify spending $4 (or more) on a pack. It is much, much harder to sell packs based on cards for nonrotating formats. When the Standard power level rises sharply to do so, there comes the risk of damaging confidence and engagement, as with the bans of Once Upon a Time and Oko, Thief of Crowns.

But what happens when Standard no longer generates demand for the supply of boosters? Standard play has heavily migrated to MTG Arena, a separate business model and economy from paper Magic. The fewer people that play paper Standard, the less valuable Standard cards become, weakening Magic’s primary business model.

2020 might be the year where Magic flirts with Commander players becoming the bedrock audience rather than Standard players. One can imagine a not-too-distant future where paper and digital Magic fully diverge: one founded on eSports and Standard with digital-only expansions, the other catering heavily to Commander players and less so to Pioneer and Modern players with fewer traditional expansions and more preconstructed products.

Sure, this won’t happen next year, and as neither a Commander nor Standard player, it may only affect me indirectly. Nevertheless, I’m concerned by how big the ripple effects will be if/when Magic changes its core audience and business model. I and many others like me might become a lower-priority audience, where our passion and purchases simply aren’t as important anymore.

Diluting the Brand

Growth is not merely a means of avoiding stagnation. Expansion can increase the size of Magic’s pie—a larger team can make targeted products to niche audiences, netting Magic more business and making customers happier. However, increased quantity of content can come at the expense of quality, especially in the transition period. Subpar content can tarnish a brand as a whole and result in a smaller pie and wasted resources. Magic has tested plenty of waters this year, between Secret Lair, Brawl Decks, Collector’s Edition, and Collector’s Boosters, but let’s instead focus on the fascinating discussions Mark Rosewater‘s had regarding Mystery Booster playtest cards.

The playtest cards seem charming—they’re effects we’d never see printed, they’re in-jokes about GDS3 and Domain, and they all have simple artwork like Look at Me, I’m the DCI. They’re not real Magic cards, since they’re not legal in any format. Except, they are real Magic cards. They are produced by Magic, come in Magic boosters alongside Magic cards, and represent Magic’s brand just as much as Jace, the Mind Sculptor does. Most players likely won’t see the distinctions between them, Un-cards, the HasCon promos, and the silliest art from Secret Lair; but the playtest cards lack Wizards’ stamp of approval. They were never playtested, don’t resemble premium products, took far less effort than anything else Magic produces, and aren’t guaranteed by Wizards to be fun to play with. They are intentionally lower-quality products, but they nevertheless are lower-quality products. That is an incredibly dangerous thing for a company to do unless it has perfect marketing.

As Magic continues to innovate, experiment, and broaden both its target audiences and product lines, it runs the risk of changing too much, too fast and sacrificing quality for quantity. It certainly happened with Magic’s story. Arguments can made that Mythic Invitationals, playtest cards, Mythic Edition, and Standard all suffered from damaging drastic changes. That in the hopes to make more products for more people, Magic’s flagship products instead stopped being for them.

Putting it all Together

I’ve been trying for months to understand my anxiety. Magic is making more products that aren’t for me, like the 2020 Commander line, Collector’s Edition, and probably Secret Lair. At the same time, products that are absolutely for me, like Ultimate Masters (which I absolutely adored) have been discontinued. Products like Modern Horizons are ostensibly for me, but Magic’s repeated mishaps with overstuffed release schedules (a problem that will only worsen as Magic adds more product lines without overhauling its marketing) made it difficult to play. The related issue of insufficient paper demand has been exacerbated by competitive play migrating to MTG Arena, the death of PPTQs, and the curtailment of Grand Prix coverage and attendance.

I’m afraid that Magic is leaving me behind, that I’m no longer in Magic’s core audience. I’m afraid that Magic is increasingly relying on FOMO to drive sales (seriously, reread Kristen Gregory’s article for an excellent, alternate, and far more concise take on everything said here) as it produces a greater quantity of products at premium prices while quantity threatens to dip. I’m afraid that as someone who doesn’t enjoy Commander but loves Limited, I might soon be as important to Wizards as a Pauper player. I’m worried that Arena’s success will further weaken paper competitive Magic and that Arena’s failure would do similar damage via tarnishing the brand.

In short, I’m afraid that this product, Magic, might stop being for me. That thought scares me—Magic has been an enormous part of my life, both for the nine years I’ve actively played and the twenty-five it’s been in my life. I’ve been to weddings and bachelor parties of friends made through Magic. Heck, I make a living designing board games because of Magic. I’m here writing for Hipsters because of Magic. I don’t want the dance to end, I don’t want to stop playing Magic, and I don’t think I’ll have to. But I’m afraid that Magic is, intentionally or otherwise, giving me signals that maybe, just maybe, I should.

As always, thanks for reading.

—Zachary Barash is a New York City-based game designer and the commissioner of Team Draft League. He designs for Kingdom Death: Monster, has a Game Design MFA from the NYU Game Center, and does freelance game design. When the stars align, he streams Magic (but the stars align way less often than he’d like).