All forms of media have different affordances.* For example, books are great at telling stories via text; they naturally lend themselves to linear narratives or stories meant to be told in a certain order. Movies are a similar medium, but their method of telling stories is audiovisual, rather than textual. Video games can likewise tell heavily-structured narratives as books and films do (as in Final Fantasy and Uncharted), but they can also have flexible or open-ended narratives (as in Mass Effect, Civilization, and even Minecraft). No medium is locked into telling certain kinds of stories—picture books, silent films, and text games blur the lines between and affordances of these media, but each has innate advantages and disadvantages. It can be easy to miss a plot-critical conversation in a video game, but doing so with a book or film involves not paying attention or skipping ahead. The important takeaway is that every medium has certain innate advantages and disadvantages, and this is absolutely true for Magic cards.

* Affordance: game designer speak for “something that a medium allows you to do.” A book has the affordances of being readable, of having physical weight and pages to be turned, of having textures, and being touchable. It is less often, but not outside the realm of possibility, for a book to afford smelling or hearing (unless you’re using scratch-and-sniff technology or an audio greeting card). These affordances enable certain kinds of behavior and interactions, but also make other kinds of interaction less possible.

Cards are not the easiest medium for telling coherent stories. Wizards of the Coast cannot control which cards a player engages with or in what order. Folks are going to get cards from random boosters or preconstructed products. WotC can control the order in which cards are spoiled, but interacting with a digital page is more akin to interacting with a book than it is a card.

Now, this doesn’t mean that Magic can’t tell stories via cards (clearly it tells a variety of stories); Magic simply has to consider how players engage with the medium and design its stories with that in mind. Today, in honor of Throne of Eldraine (Magic’s upcoming set based on Western fairy tales and Arthurian legends) we’ll cover a variety of ways that Magic has told its stories. There are three broad types of narratives Magic has told: traditional, Magic-specific, and individual. We’ll start with the one we’ve arguably seen the least of lately: traditional narratives.

Traditional Narrative

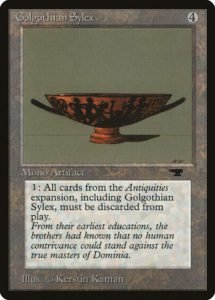

Magic’s first major characters were Urza, Mishra, and the Phyrexians. You could learn bits and pieces about them from Magic cards, but Golgothian Sylex, Mishra’s War Machine, Urza’s Miter, Tawnos’s Weaponry, and Ashnod’s Altar don’t tell you much about them or their conflict other than their names. To know the story, you needed to consume non-Magic forms of media, namely books. This is a trend that continued for much of Magic’s existence until Khans of Tarkir—while Magic got better at telling stories via cards themselves over this period (which we’ll cover in more depth), to know even the major story beats or details about major characters, you needed to read a book or short story and not play with Magic cards.

Magic’s first real foray into telling a traditional narrative via cards was in Tempest. While that was an amazing block, it had some growing pains when it came to storytelling. Every card in the set tells one brief snippet of the story, which is a cool idea; but doesn’t work well given that you have no control over the order in which the cards are seen. To boot, there is no numbering system to order these events; so even if you have access to the entire set (which is by no means a given in 1997, the internet wasn’t close to the repository of human knowledge that it is today), you would need time and guesswork to make sense of the story. And finally, it seemed the story was being patched after-the-fact to cards, rather than cards being designed to tell a story moment. That’s why there are so many cards communicating Gerrard falling off the Weatherlight (Sudden Impact, Abandon Hope, and Broken Fall, a moment also shown on Capsize but without any explanation) but it is hard to tell what the Weatherlight crew is trying to accomplish on Rath.

As Magic got better at communicating story (or at least a feeling) through its cards, the need for books telling traditional narratives diminished. This culminated in the two Robert Wintermute books for Zendikar and Scars of Mirrodin blocks, which were of such low quality that they have been mostly ignored or retconned, and saw the temporary cessation of Magic novels. After several years of Magic’s story primarily being available for free on Daily MTG (in the form of short stories and occasional comics, with some eBooks and physical comic books available as well), this model is ending and Magic is returning to having books once more.

This has advantages, as there are incredibly talented authors available for freelance work that would not be on the in-house Creative team (such as Kate Elliot, who did amazing work on the Core Set 2019 story). However, there are demonstrated challenges that can arise from working with outside writers, as they may not be familiar with Magic’s story (leading to notable continuity issues with Dominaria) or their distance from Magic teams may make it harder for their creative calls to represented on Magic cards (which led to a certain Planeswalker dying off-camera during War of the Spark).

One of the most important innovations in traditional storytelling was subtle but critical. With the creation of the Gatewatch (which we’ll cover in depth when we discuss Magic-specific narratives), Magic became much better at not only communicating story through cards but at telling stories that can be told by cards. With these innovations came diminished need for books and short stories to communicate major plot points—people could figure out the major plot points and players just from looking at the cards. Text stories instead were used to accentuate and flesh out stories, rather than explain them.

Likely the best such example is Imprisoned in the Moon. This card tells the end of the Eldritch Moon story, where Emrakul is defeated—unless you read The Promised End and know that this is the moment of Emrakul’s triumph. The story not only provides context to the plot, but it can subvert it, providing exciting secret tidbits for those who love diving into the storyline without undermining the broad audience’s understanding.

Hopefully, we’ll see more such stories that aren’t required reading for understanding what is going on but are exciting for those who are compelled to read. We’ll get more into the innovations that enabled this status quo next time, but there may be a bit of a break before we touch on Magic-specific narrative and individual card narratives—Throne of Eldraine spoilers do begin shortly, after all. Hopefully you’re enjoying this foray into story design. As always, thanks for reading.

—Zachary Barash is a New York City-based game designer and the commissioner of Team Draft League. He designs for Kingdom Death: Monster, has a Game Design MFA from the NYU Game Center, and does freelance game design. When the stars align, he streams Magic (but the stars align way less often than he’d like).

His favorite card of the month is Lava Axe. It’s not a powerful card, but it’s simple and lends itself to powerful moments. There’s something elegant about a card that looks great to an inexperienced player, looks terrible to an intermediate player, and presents an interesting choice to experienced players. Oh, and it lends itself quite well to awesome flavor text.