Today, let’s talk about cheating in Cleveland and what it tells us about game design. This isn’t about a certain MPL player and Cry of the Carnarium, but we’ll get to that card in a bit. No, this is about me cheating. Oh, it was accidental, but I absolutely benefited from using a card illegally. And that was but one of a series of small but substantial card misunderstandings witnessed at the Grand Prix.

Slipping Underneath

It’s round four of Grand Prix Cleveland and things are not going well. My sealed pool was hard. I used up all the time in deckbuilding, but wasn’t confident in my deck’s power or my choice of colors. Over the course of the weekend, I showed the pool to eight people and received seven confident recommendations of different color combinations I should have played (which is both a reflection of how deep Ravnica Allegiance Limited is and how all erratic the pool was). After thoroughly thrashing my bye in round one, I lost my round two feature match (which, admittedly, had zero spectators beyond our judge) and round three, taking no games in the process. Things looked bad.

I sat down to play round four against a nice local player, knowing that I couldn’t afford to lose another match. I managed to get an early advantage, playing a Sauroform Hybrid into a Steeple Creeper while my opponent failed to put up defenses. He tried to Bring to Trial my Steeple Creeper, I flashed in Faerie Duelist to shrink it below the restraints, and won pretty handily.

That evening, after a disappointing 3-3 finish and a fun side event draft, I thought back to this unusual interaction and chuckled about its flavor—my faerie poked my frog snake in the eye, which weakened it enough to fall right through its restraints. Faerie Duelist is delightfully silly and yet surprisingly potent, making it one of my favorite simple designs in the set, and it felt good finding this unique use for it. And then I remembered Faerie Duelist‘s full text: it can only hit opponents’ creatures. It can’t annoy a friendly Steeple Creeper to save it. The unique use was cheating. Not a malicious or intentional cheat, mind you, but a nevertheless illegal play deserving of a warning.

Templating Tension

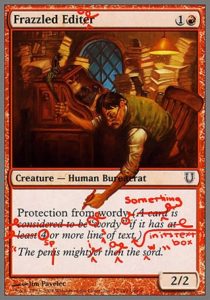

Faerie Duelist is templated differently than similar effects in Ravnica Allegiance. It’s legal to Grotesque Demise your own creature or Arrester’s Zeal your opponent’s creature, even though there’s hardly any reason to do so. Why can’t Faerie Duelist give you the same option, even if the vast majority of the time you’re going to use it to shrink your opponent’s creatures?

The answer is digital. Digital Magic benefits from having a minimal amount of clicks (and opportunities for misclicks). If Faerie Duelist can target your own creatures, its ability wants to be a may trigger, not a must (as it currently is). As a may trigger, you will be asked “Do you want to use this ability? Yes/No” every time you cast a Faerie Duelist. If you play it when your opponent has no creatures but you have two in play, you’ll have to select a target from among your own creatures (a pointless choice and a click) and then probably select “no” (a second click, and one which you can accidentally mess up). This additional click would happen 100% of the time someone casts Faerie Duelist, all to create the possibility of countering Bring to Trial—or turning off your Flames of the Raze-Boar when you don’t want to splash-kill Afterlife creatures, or letting you block a Footlight Fiend without killing it when you’re at one life, among other hackneyed scenarios. It’s probably not worth making the card slightly more onerous to play 100% of the time to open up some additional utility in less than 1% of all cases.

If Magic were only focused on the tabletop play experience, clicks would be a non-issue and Faerie Duelist could have this tiny bit of lenticular design (hidden uses that experienced players can find). However, digital Magic is bigger than ever and needs the smoothest experience that card design can afford, even if it comes at the expense of some minor utility. This is the obvious tension between digital and tabletop Magic, but there’s another one: how information is tracked.

Chunking Information

Our brains constantly simplify, interpret, and chunk the information they receive. Magic is a game overflowing with information. There are 136 creatures just in Ravnica Allegiance (not including the four creatures in the Planeswalker Decks or The Haunt of Hightower), and you really need to know all of them at least vaguely to play Limited. Every single one of them has a mana cost, creature type, color, power, and toughness. Five are vanilla, but 131 have unique rules text. That’s a lot of information to process.

Thankfully, keywords like Riot and Flying provide helpful shortcuts and categories to help us process and remember all this information, and ability words let us categorize mechanically disparate cards together under some unifying principles. These rules are shortcuts we’re meant to use alongside all the other shortcuts we make for ourselves, all so that we can focus less on what the cards do and more on how to use them in a game. However, the way our brains create shortcuts can lead to pitfalls.

Oversimplification

Sometimes you forget rarely relevant but crucial restriction. I chunked Faerie Duelist as a trick that gives -2/-0, and in so doing, forgot that it has an additional restriction. An opponent of mine in the MCQ forgot that Guardian Project has a restriction and almost drew a card when he had a duplicate creature in his graveyard, all because that card when simplified says, “your creatures cantrip.”

Secondary Details

Sometimes, you only remember a card’s most relevant ability. You’re only ever going to put High Alert in your deck for the dramatic Doran, the Siege Tower effect. However, it has a second, thematic (and much weaker) ability that my opponents seem to continually forget and so walk into my untappable Senate Couriers.

Bucking Precedent

Sometimes, cards resemble previous cards but function differently. Green has many Regrowth effects, but almost none are instants, and all the ones that get back multiple cards are sorceries (with Reap as the one outlier). I’ve seen plenty of people not recognize Regenesis is an instant because they don’t expect it to be one. Cry of the Carnarium looks exactly like Flaying Tendrils, except it inserts a completely unrelated (and never done before) sentence in between two related lines of rules text.

The Trouble with Smart Games

The second tension between digital and tabletop Magic is how information is processed (and accordingly, how the game state is maintained). Tabletop games are processed by human players and benefit from chunkable rules that can hide some lenticular design. They benefit from versatile targeting (rather than Rakdos Firewheeler‘s restrictive targeting) and may triggers. Digital card games benefit from stricter target and must trigger, since they reduce clicks and potential misclicks. They can have much more complicated (or even random) game states because the rules engine takes care of all the little things. In Arena, players don’t have to constantly keep track of whether creatures have died every turn just in case someone casts Cry of the Carnarium because the game will. If a player tries to pull the same stunt as I did with Faerie Duelist, they’ll be confused for a moment when the game won’t let them target their own creature, then realize their mistake as the game shows them the only legal targets.

When rules engines are in control, players might not be expected to remember (or even be able to remember or process) everything that their cards do. Digital cards are often templated to function smoothly, even if they may sometimes go against player intuition. I wonder if perhaps Ravnica Allegiance has gone a bit too far in accommodating Arena while simultaneously pushing the upper limits on complexity—there are a lot of cards doing a lot of different things, yet not always the same way as similar cards in the same set. Like Mass Manipulation and Hydroid Krasis, which use disparate double X costs, despite double X costs being among the most confusing things in Magic.

Getting complexity right is a balancing act, one almost impossible to get spot on. Ravnica Allegiance is a deep format partly because its diversity of effects enables a wealth of archetypes, but it’s also a mentally taxing format for much the same reason. This mental exertion is compounded by design decisions intended to improve the digital experience and to take advantage of digital rules engines. The future of Magic may well be digital—and in many respects, that future is now—but Magic is still a game played by millions of people on tabletops. It’s possible that the jump to Arena may have accidentally made Ravnica Allegiance less accessible than the average set in Magic’s original format. This could be the beginning of a trend, or it could be a momentary spike caused by Arena development, R&D experimentation, the pendulum of complexity swinging around, or any number of tiny factors. It’s simply something to keep an eye on, and for that, I have Faerie Duelist to thank and a very nice opponent from Cleveland I owe an apology to.

And, as always, thanks for reading.

—Zachary Barash is a New York City-based game designer and the commissioner of Team Draft League. He designs for Kingdom Death: Monster, has a Game Design MFA from the NYU Game Center, and does freelance game design. When the stars align, he streams Magic.

His favorite card of the month is Coat With Venom. It does a whole lot for a single mana and heralded the design of many more flexible combat tricks. Plus, it’s a solid combat trick that neither cantrips nor provides a massive power buff, which is hard to do.