The Ravnica Allegiance prerelease provided me an opportunity to represent the Simic Combine, to prepare for MagicFest New Jersey, and most importantly, to play with brand new cards! Between paper events, paper testing with friends, and MTG Arena, I had the luxury of getting to try out every guild across several drafts and Sealed events.

Normally I’d aim to have a Limited guide ready by now, but the format has both an above-average number of mechanics and complexity, making it quite the tough nut to crack. There was, however, one undeniable piece of data from this weekend. Everyone suspected that Ethereal Absolution would be bonkers. And they were right. The card is almost unbeatable. It spawned endless conversations about its power level, its design, and whether it ought to exist.

Today on Drawing Live, we’ll dive into the design of bombs and what I’ll call mega-bombs (the most powerful bombs). We’ll come up with means of classifying and delineating bombs, providing the tools to evaluate Ethereal Absolution, both on its own merits and within the context of Ravnica Allegiance.

In Praise of Bombs

To clearly define our terms, a bomb is a powerful, proactive Magic card that can win the game single-handedly or dramatically shift the game state in one player’s favor. Bombs can take many shapes and forms, from a generically powerful card like Grave Titan, to an archetype-specific powerhouse like Kumena, Tyrant of Orazca. Bombs can be artifacts like Sword of Fire and Ice, enchantments like Citadel Siege, lands like Library of Alexandria, and Planeswalkers (the majority of which are bombs). Bombs are not always threats—Library of Alexandria, Kumena’s Awakening, and Dryad Greenseeker dominate game states by producing insurmountable card advantage. Bombs are not always rare, either—Charging Monstrosaur, Tatyova, Benthic Druid, and Nightveil Predator are three recent superpowered uncommons.

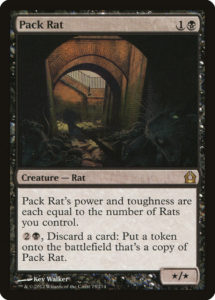

Mega-bombs have a looser definition, but they’re the best of the best in their respective formats and particularly effective at winning the game. These are cards like Ugin, the Spirit Dragon, Pack Rat, Glorybringer, and Profane Procession.

Bombs are vitally important to Magic. They constitute many of the most exciting, powerful cards. They allow enthralling, swingy games. They make players want to purchase boosters. They are essential components of Constructed, are important tools for players to form heuristics with, and are some of the main tools by which skill differentials can be both tested and surmounted in Limited. Bombs can be frustrating to lose against, but they serve an important purpose. That said, there are different kinds of bombs, some of which are more frustrating than others.

Classifying Bombs

There are five classifications I’ll give to bombs: cost, immediate advantage, rarity, interactability, and speed. Here are our definitions of terms:

Cost combines three aspects: converted mana cost, color commitment, and whether they need setup in order to function. The more expensive, color-committing, or archetype-specific a bomb is, the harder it is to use and the weaker it tends to be.

Immediate Advantage tracks whether a bomb does something as soon as it’s played, or if it has a cheap ability that can be used immediately.

Rarity is pretty straightforward. In general, it’s best for Limited when the most powerful bombs (basically, all the mega-bombs) are mythic rare. This restricts their ability to completely dominate games to a small fraction of events while allowing them to powerfully affect Constructed.

Interactability is a measure of how easy a bomb is to answer.

Speed is a measure of how quickly a bomb can win the game.

Let’s evaluate a smattering of bombs according to these criteria.

One of the most powerful mega-bombs of all time, Pack Rat was almost certainly more powerful than its creators expected.

Cost: Very low.

Immediate Advantage: High. If you had five mana when you played it, or if you untapped with it on turn three, your victory was all but inevitable.

Rarity: Too low. A card this overwhelmingly powerful really wants to be mythic.

Interactability: Low. Normally, a two drop 1/1 is easy to kill, but there weren’t many things that could kill it on sight. As soon as it made a token, the game was over.

Speed: High. This attacks for six on turn four and twelve and turn five. That’s really fast.

A giant, elder dinosaur. There are five others like it, but only this one flies.

Cost: Very High. Eight mana is a lot to ask, even in a format with treasure.

Immediate Advantage: Very Low. You get a big blocker, but if your opponent has a one-for-one answer, you’re up nothing.

Rarity: Appropriate.

Interactibility: Low. Indestructible creatures are very difficult, though not impossible to deal with.

Speed: High. Eight damage is a turn is quite the clock.

Cost: Very High.

Immediate Advantage: Low. A bit of life is a nice cushion, but paying seven mana for seven life isn’t exactly great.

Rarity: Appropriate. This is a splashy, weird spell that definitely shouldn’t be uncommon, but isn’t so crazy in terms of design or power that it must be mythic.

Interactability: Extremely Low. If you aren’t playing blue for countermagic or black for discard, there is nothing you can do to stop this short of winning the game. Yes, white has Meddling Mage effects in is color pie, but it didn’t have any such cards in Amonkhet.

Speed: Very Low. Eight turns is a lot.

Cost: Medium. Five mana isn’t a ton to ask and Ral is playable or splashable in three of the five GRN guilds. He does have a deckbuilding requirement to maximize his utility, but he’s still great if you’re only able to use him to cast Nagging Thoughts.

Immediate Advantage: High. Ral immediately puts you up a card or your opponent down a creature.

Rarity: Appropriate.

Interactability: Medium. Planeswalkers are difficult to interact with directly, but they are vulnerable to creatures.

Speed: Medium. Ral won’t win the game by himself, but after two turns of him being on the field, you’re probably incredibly ahead and likely able to close the game out.

Cost: High. Seven mana is a lot to ask, even for a monocolor card.

Immediate Advantage: High. This downgrades your opponents’ large creatures to medium-sized, their medium-sized creatures to small, and their small creatures to dead. It also sets up your side for an immediate attack.

Rarity: Appropriate.

Interactability: High. Elesh Norn is a creature with no protection.

Speed: Medium-High. By herself, Elesh Norn is a medium-speed clock. Alongside any creatures whatsoever, she provides massive damage.

Cost: Medium. Six mana is about the upper bounds of a reasonable cost and Tetzimoc requires an additional initial mana investment for full value. Still, this is a single color card.

Immediate Advantage: Very High. Tetzimoc will probably destroy all important creatures your opponent controls. And then you’ll still have a 6/6 deathtouch. Plague Wind is an insane ETB effect on a massive six drop.

Rarity: Iffy. Tetzimoc really threw off the balance of Rivals of Ixalan Limited, but has yet to prove powerful enough for Constructed. It wouldn’t move product as a mythic, but it’d sure warp Limited a lot less.

Interactability: Extremely Low. Tetzimoc is vulnerable to hand disruption and countermagic, so Naya mages are out of luck.

Speed: Medium/High. Tetzimoc in the hand is a slow grindfest, and your opponent is going to see the haymaker coming a mile away. A resolved one will destroy your opponent’s board, then your opponent.

Cost: Medium. Three mana is a small initial investment, but you need to put in eight before this does anything. Also, two colors is a bit of an ask (though three of the four tribes in Ixalan can play or splash this).

Immediate Advantage: Low. Unless you have eight mana, this does nothing the turn you play it (except demonstrate to your opponent how they’re going to lose).

Rarity: Iffy. This has the same issues as Tetzimoc, Primal Death—it was probably too strong for Limited at rare but wasn’t meant for Constructed.

Interactability: Very Low. Enchantments are impossible for black and red to deal with. Blue can only bounce or counter them (and it’s hard to counter a three mana spell). Only green can answer this both before and after it flips.

Speed: Very Low. This spends several turns wiping your opponent’s board, then several turns bringing those creatures back.

Cost: Medium-High. Three of the five guilds can play or splash Kaya’s cleansing, but six mana is still high.

Immediate Advantage: High. The effect isn’t as dramatic as Elesh Norn, Grand Cenobite‘s, but it’s quite comparable.

Rarity: Iffy. Like the two previous cards, Ethereal Absolution doesn’t appear to be intended for Standard, but its dramatic effect on Limited makes it a bit too common at rare.

Interactability: Extremely low. I’ll talk more about this in a moment.

Speed: Medium-Low. This doesn’t make your creatures enormous, but it’ll force your opponent into submission over several turns, and every trade gives you more 2/2 spirits.

Interacting with the Uninteractive

Elesh Norn, Grand Cenobite, Tetzimoc, Primal Death and Profane Procession are all similar to Ethereal Absolution. Elesh Norn has the closest effect, whereas the latter two share Ethereal Absolution‘s low interactability, suspect rarity, and play pattern. The frustrating thing about your opponent playing a Profane Procession or putting a prey counter on one of your creatures is the immense feeling of helplessness. Unless you could immediately win the game, playing any more creatures would just make your opponents’ bombs better. Their Tetzimoc would get to kill more things, their Profane Procession would let your opponent steal better things. Ethereal Absolution plays in a similar vein in that it doesn’t win the game immediately, but it provides the tools to win over a series of turns. I’d argue this is a lot worse than something like Approach of the Second Sun, which is inevitable but has a high cost and little immediate impact.

The biggest issue I have with Ethereal Absolution is its unusually low interactability. Almost all formats have several answers to enchantments, usually ones which live in sideboards most of the time. Ravnica Allegiance has far less enchantment removal. At common, there is Expose to Daylight and nothing else. At higher rarities, you’ve got Mortify, Sunder Shaman, Cindervines, Deputy of Detention, maybe Eyes Everywhere, and the awful Rampage of the Clans. The proactive solutions are Drill Bit, Quench, Thought Collapse, Frilled Mystic, and Absorb. That’s a huge problem, particularly for a bomb that doesn’t end the game quickly. It’s agonizing to lose to something that ends the game immediately but forces you to keep playing anyway—think Jace, the Mind Sculptor or Teferi, Hero of Dominaria.

How did this happen?

I believe the dearth of enchantment removal in Ravnica Allegiance was a deliberate choice. The set has an inordinately high number of cool, powerful enchantments. You’ve got High Alert, Angelic Exaltation, Dovin’s Acuity, Ill-Gotten Inheritance, Simic Ascendancy, Verity Circle, and Theater of Horrors, to name about half. If folks were main-decking Crushing Canopy then entire archetypes might be too difficult to foster. If blue had access to Disperse, then Eyes Everywhere might be far too good. Reducing the amount of enchantment interaction to almost nil means more folks get to do more cool things.

This logic reminds me of that which led to the unfortunate Shadows over Innistrad Standard environment: graveyard-based decks were the cool thing, so graveyard interaction disappeared from Standard. When the best (and only) way to hate on graveyards was Learn from the Past, folks couldn’t stop Emrakul, the Promised End, no matter how much they wanted to. I don’t believe Ravnica Allegiance ought to have strong, main-deckable enchantment hate like Crushing Canopy, but why can’t it have several narrow sideboard cards like Appetite for the Unnatural, or even a 1/2 Priest of Iroas? Why is there a flexible, powerful sideboard hate card in Deface but no such corollary for enchantments?

As a game designer and lover of Magic, I deeply respect the work of Wizards of the Coast. I recognize that Magic is a game for hundreds of different audiences and needs cards which cater to a large variety of players (many of which I am not a member of). I believe that low interaction, slow mega-bombs like Profane Procession and Ethereal Absolution have their fans, but they’re generally bad for Limited (when not at mythic) and that it was a mistake to print so little enchantment hate in Ravnica Allegiance.

Formats with over a dozen powerful enchantments need more enchantment hate than normal, even if all of that hate is weak and not maindeckable. A single common answer is woefully insufficient, and there isn’t even a splashable green uncommon Naturalize. Ravnica Allegiance is chock full of splendid new designs, but I’m concerned that they rest on a foundation with one stone of dangerous logic. Here’s looking forward to seeing how the format plays out this weekend.

And, as always, thanks for reading.

—Zachary Barash is a New York City-based game designer and the commissioner of Team Draft League. He designs for Kingdom Death: Monster, has a Game Design MFA from the NYU Game Center, and does freelance game design. When the stars align, he streams Magic.

His favorite card of the month is Growth Spiral. Explore is one of his favorite designs ever, and this is not only the same card, but it avoids the complexities of playing extra lands. Also, have you seen that artwork by Seb McKinnon?