The construction of a Commander deck is an anomaly in Magic. While a Standard deck will grow and evolve over its time in the format or a Legacy deck might take on new parts as an old card get outclassed; a Commander deck can have a storied history with dozens of alterations over years, finally reaching a desired state of perfection. A perfect Commander deck is completely subjective, as available card pool, a color identity, a general, and personal tastes allow for any deck to be unique from any other deck. I have several decks that I would like to think are perfect for my tastes, so much so that in the face of a general that might fit the deck better or an objectively better card by another player’s metrics, I have often passed on making alterations or changes.

To players who haven’t gone deep on Commander or at least don’t see how a Magic deck can truly encompass personal expression, this week I would like to offer my thought process behind answers to questions like: Why wouldn’t you want to build most optimally? How do you go from EDHrec’s version of Doran, the Siege Tower to Doran, your personal spirit animal? And how can you recognize when your deck has become somebody that you used to know?

Player Avatar

Your general, the generally agreed-upon defining aspect of Commander, is a critical choice of building a Commander deck. When I first discovered Commander/EDH, the deck construction was daunting, but the format was immensely fascinating. The selection of a general was extremely personal to me in ways I don’t know that I understood. It would be a few years until I would see why picking a general could be so personal thing to some players, about the time many of my friends get into League of Legends and later Overwatch. I’m a slow learner sometimes, so the linkage between why my friends would get very connected to certain characters for different styles of play, even down to completely cosmetic character skins and how I reveled in playing certain legendary creatures for different styles of play didn’t click until maybe two years ago.

Some people play Alesha, Who Smiles at Death because she can win fast as a Weenie Reanimator strategy, some just want a Mardu deck, and others see themselves in the game through her transgender backstory. I uncovered this revelation when I built my Doran, the Siege Tower deck just as Theros block was wrapping up. Then, not long after Anafenza, the Foremost was previewed, my playgroup’s frequent biggest threat, Alex, pointed out that she was a better legend to helm the deck—both because she enhanced the creatures of the deck in play and had a static ability that fought creature recursion. Those points were entirely valid, but I had wanted to build a Doran deck that did Doran stuff, not fight creature recursion. Doran is my Abzan player avatar. Once you find your general, you might stick with that general far past the point where a more optimal general gets printed, because it was never about being optimal.

Aesthetic Personalization

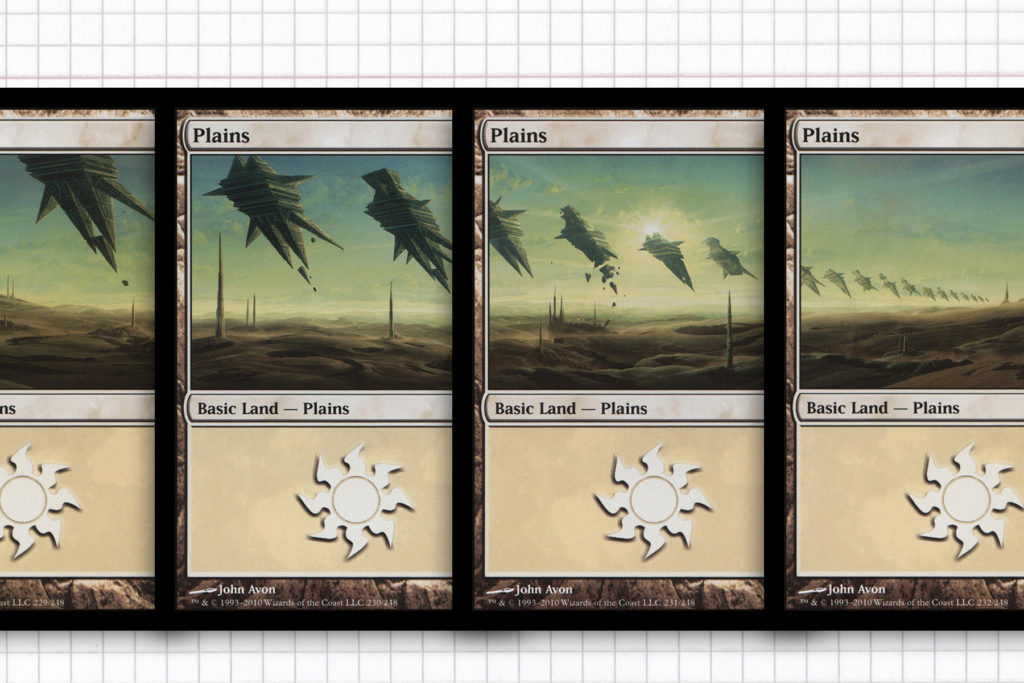

I think the yearly pre-constructed decks are a net positive, both as a method of getting new cards into Magic that would not survive to print in Standard and as a shorthand for new players to enter the format. They create an issue I felt but once again could not put my finger on, until I stumbled across the Better Basic series by James Arnold on Gathering Magic. While I have always been a fan the art of Magic, for the first decade of playing the game I only ever thought about the art in terms of the creatures, enchantments, artifact and spells. Suddenly, James’ series made me see even the lands I selected could be an extension of the aesthetic of the deck. In that moment, I realized what had been off-putting about the Commander precons for me: with a high enough concentration of those cards in a deck, it didn’t feel like my deck.

Most players may never reach the state where particular printings of a card matter. Path to Exile in all its printings works the same. Who cares if one features a leonin and another Venser? But of my own omission, I do. Taking Crater Hellion from Commander 2013 and my Urza’s Saga copy as in example, even if the only thing separating the two was a set symbol and the frame, over time one would belong in the deck and one would be trade binder fodder. I admit that’s a weird stance to take, but to me it matters. I recall taking a copy of Nature’s Lore from Portal out of a deck and replacing with a copy from Ice Age when I was refacing Jesse’s The Ur-Dragon deck, so that Jesse would have a version with clearer rules text. Over time it didn’t feel right. I had to get another Portal copy. The only way I can describe the feeling of drawing the “wrong” version, is that one version had transcended the physical card, becoming part of the aesthetic whole of that deck. Drawing any other version felt incorrect.

Accept Change

Making alterations and changing a deck are two different things to me. In the alteration process, you’re working towards fulfilling the central thesis of the deck. Substituting Armillary Sphere for Sword of the Animist, because you’re certain the former will yield more land development, or replacing Primal Rage with Gruul War Plow, because being colorless is more beneficial then costing twice as much mana. This might be the part of the process I enjoy the most: no more theorycrafting. You’re playing games for the repetitions needed to identify what cards are doing what you’re looking for in a deck and which cards were poorly-conceived ideas.

The process of changing a deck is a different animal to me, taking a deck and making sweeping revisions to the point where the deck no longer identifies the same. A negative version of this happened to me when I changed my Sygg, River Guide deck to a Sidar Kondo of Jamuraa/Thrasios, Triton Hero deck after Commander 2016 came out. The idea was to still remain a Merfolk deck, but open up my possibilities to Bant. The issue was not that deck was bad in games—Thrasios can win games on his own—but it was no longer the deck I loved and I stopped bringing it with me to Commander game nights. Eventually that deck would be broken apart to make the Sygg and Kumena, Tyrant of Orazca decks I have today, two similar tribal decks that play surprisingly differently.

But change can be positive as well, such as when you realize that what you were trying do and what you’ve built are not aligned with each other. This happened when I built Derevi, Empyrial Tactician in the style of a casual deck I once had nicknamed “I’d Tap That,” in which tapping down the rest of the table and winning by attrition was my main road to victory. The Bant colors all have ways of tapping permanents and interacting with them once tapped, I thought I had picked the best general for the job—she literally tapped things! But something wasn’t right; and no matter how many times I tried to make search parameters that might feed me new cards to try, nothing was a good fit. Then I took a step back and asked myself if I was even using the right colors. I eventually concluded that Esper was the color identity for me, replacing the slow and methodical gameplan of green with more direct removal and aggression of black. By changing over to Dakkon Blackblade I got the colors I needed and a late game finisher who performed alpha strikes by himself.

An Eldritch Love Story

The culmination of all of these elements can be summed up by my Shattergang Brothers deck, which in its first two years of life truly went from something I loved, to something I no longer recognized, back to one of my two favorite decks. While the deck is ever-evolving, the general look and feel of the deck is similar to what I had written about last year, a Jund deck that’s main theme was being colorless through its use of Eldrazi. But at the time of that article being published, that deck was actually a Yidris, Maelstrom Wielder deck. At its peak the deck was very powerful, for a four-color deck I had very little trouble getting my colors and the addition of blue aligned Eldrazi made for something very unpredictable.

Over time I reflected back on the year I had spent fine tuning the deck between the release of Battle for Zendikar and Commander 2016, before foolishly making the swap. The cards were all on theme, but once again, the deck in its Jund form had transcended the cardboard and become something deeply personal to me. Even when I shifted the deck back, I looked at all the other Jund generals available and still couldn’t escape the fact the goblin trio was still the right call, even though I rarely cast them. The lands, creatures, art, sleeves, and profile of the deck amongst my group were all creating something greater than the sum of all the parts. To an outside observer it probably sounds crazy, but I didn’t realize what I had until I changed the deck, then had no choice but to change it back.

This article was supposed to be about the process of updating a deck. I can certainly say that this did not go the way I expected, but that idea maybe something I come back around to in a month or so when I figure out what I really want to say on the matter. Instead I leaned into some psychology of a deck builder and then could pull myself back up enough, resulting in a deep dive into my own mania. I hope something could be gleaned from all of this. If not, we come back next week with something a little more on-track with my general direction for the column and forget all this silliness. Let me know if this was at all helpful. Until then, thanks all.