Back when I was a senior in high school—now two decades ago!—my AP U.S. Government teacher had us write our own multiple choice final exam. Each of us wrote twenty or thirty multiple-choice questions covering the range of our syllabus. We got graded on their accuracy and difficulty. Then he chose the best 100, and that was our final exam. I missed four questions. Three were ones I wrote.

My post-secondary life has followed many paths. Among them, I was an SAT and GRE instructor for Kaplan, which is a major exam prep company. In that role, I saw up close the pedagogical methods that lead to success on multiple choice exams. Kaplan didn’t involve me in their in-house question-writing, but I could study their techniques well enough.

Multiple-Choice Design Theory

There are two big questions facing the constructor of a multiple-choice examination: how difficult should it be to answer the questions, and how much do you need to stratify the performance of examinees? You could call these “difficulty” and “curve” for simplicity’s sake. The two questions are deeply related, but they benefit from separate analysis.

Let’s look at difficulty. How do you make a multiple-choice test more difficult? Here are some common ways: broaden the scope of knowledge tested, decrease the clarity of the questions, make the answers less correct, add more choices to each question, embed multiple questions within one question, decrease the time of the examination, significantly increase the total number of questions, limit the resources available during the test, and limit the resources available to prepare for the test. Those are a lot of parameters to manipulate. Many are fixed by practicality—for example, you probably can’t make high school students take an eight-hour exam for a single class, and your answer sheets probably can’t accept more than five choices per numbered question. But there is plenty to work with, especially if you know what you are doing.

What about curve? The idea of a curve is to stratify the performance of examinees into meaningful groups. If you test a group of random teenagers on the names of everyday objects, you probably won’t be able to use their test results to divide them in a way related to their knowledge of the exam material. Likewise if you give that group the American Invitational Mathematics Examination, you are unlikely to learn much about their facility with everyday math. (That is a three-hour, fifteen-question test where each answer is a three-digit number. No calculators are allowed.) Curve is the way you calibrate the difficulty of the test to the expected ability of the examinees. Standardized tests, like the SAT, can’t be too hard but must still create a meaningful distribution of scores. That makes curving a technical endeavor, unless you are lucky enough to not need to care too much about stratification. Or if you were taking the Graduate Record Examination prior to the 2011 redesign—my Math score was 80 points higher than my Verbal score, yet 8% of test-takers did as well as me on math while only 2% did as well or better on verbal. Doesn’t sound like a very effective test, does it?

Great Designer Search 3

So what does this have to do with Magic: the Gathering? Well, there was this thing called Great Designer Search 3 that used a 75-question multiple-choice test to filter all the applicants down to a couple hundred. As it turned out, you needed to answer 73 of 75 questions correctly to make the cut, which I believe was about 3% of examinees. That’s a harsh cutoff for sure.

I got 71 of 75 correct, which felt about right. When I took the test, I marked what I considered the three most difficult questions. (Saving the hardest questions until the end is a good technique on multiple-choice tests if each question is scored equally.) Of those, I got one correct. Perhaps I overthought a few others. “Prowess is trinket text on a six-drop 5/5 with menace” is probably true, but R&D must have added that ability to show the answer should be Ripscale Predator not Granitic Titan. So it goes.

Many GDS3 participants have been upset about the results of the multiple choice test. That’s not surprising since only a tiny fraction of test-takers made the cut, and hundreds (if not thousands) of the most engaged examinees scored in the 70s like I did. What did R&D do to make this test a good trial to sort the GDS3 field down to a manageable size? Let’s look at difficulty and curve.

The GDS3 multiple choice test needed to be very difficult. On some level, that’s easy to do—Magic design is an arcane field of study after all—but it needs to be difficult for the people who choose to participate in GDS3. That meant R&D could operate from a high baseline of knowledge. Let’s look at how they used each of the techniques I listed above to increase the difficulty:

- Broaden the scope of knowledge: Check. They added questions about non-obvious design concerns, for example the number of players in an R&D playtest draft, and which Modern/Legacy staples are safest to reprint in Standard.

- Decrease the clarity of questions: Check. The most common refrain I’ve seen on Twitter from upset GDS3 examinees are along the lines of “what is this question even trying to ask?” They’re asking if the color pie allows them to print Serra Angel as a Golgari card. The answer is yes.

- Make the Answers Less Correct: Check. Commander decks are now built around themes and in sets of four so they are easier to play as a group right out of the box. But the most important goal, among the five choices in #21, is to inspire players to build new decks, not that each deck has a new theme. I figured “new” didn’t make that answer wrong enough to change the credited response. Alas.

- Add more choices to each question: Nope. All the questions have five choices, except the ones about rarity, which by necessity have four. They didn’t write any questions where the prompt is a set of propositions and the question asks you to distinguish between various subsets of those propositions.

- Embed multiple questions within one question: Check. There are a few three-packs of questions about proposed card designs. Some of those, like #17, ask you to choose a color-appropriate ability based on having previously picked the correct color(s) of the card.

- Decrease the time of the examination: Nope. They gave us 24 hours. If you prepared for the exam, perhaps by following Zach Barash’s fantastic prep series, then you had plenty of time to sleep and eat a sandwich.

- Significantly increase the total number of questions: Check. The past tests were 50 questions, and this one was originally announced to be 50 as well. They added 25 more, and probably could have added another 25 if they’d wished.

- Limit the resources available during the test: Nope. They prohibited collaboration, but it was otherwise an “open-book” test.

- Limit the resources available to prepare for the test: Nope. You have to be willing to follow Mark Rosewater, and there’s a certain type of logic embedded in the questions that might be inscrutable to many, but R&D didn’t try to hide the ball. Zach’s practice questions were very representative of what showed up.

So they basically did everything they could, at least to some degree, to make the test quite difficult. They provided ample resources and time to do well, which makes sense given they are trying to find new employees, and they stuck with the usual five-choice format. But they pulled out all the rest of the stops.

How did they do on the curve part? Not so good. You could miss two questions and make the cut. That’s a fair line, but a brutal one. When one or two correct answers are decisive, the clarity of the test has profound impact on the results. Yet by making the test material less clear—which they did to increase difficulty—they decreased the reliability of marginal score differentials at the top end. If R&D cared about a meaningful curve, they would have probably made a 100- or 120-question test. That’s a lot more work if it doesn’t really matter, though.

GDS3 cuts to “top eight” after the next round, so “unfair” or “irrational” cuts were inevitable. As Mark Rosewater has explained, the purpose of the multiple-choice test was to narrow the field from around 8,000 to around 200 so his team could evaluate all of the third round submissions. (It’s a lot easier to score a multiple choice test than to evaluate essays or card designs.)

Overall, R&D did a good job of designing the test to be quite difficult even for the most prepared GDS3 participants. I was hoping to make it to the design challenge, but I can manage to find other ways to fill my February. It feels good enough to know that I was, like many hundreds or thousands of you out there, in the ballpark of understanding the mechanics of Magic design.

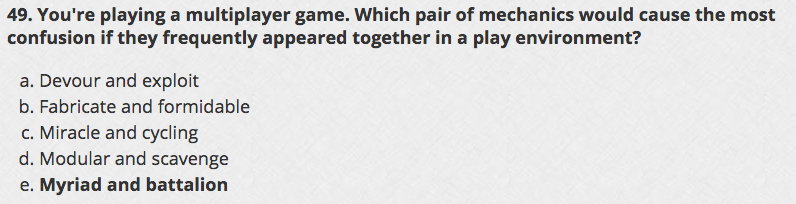

That said, I can’t leave this article without complaining about question #49.

Mark Rosewater explains that the correct answer was “Myriad and Battalion,” two mechanics with an awkward lack of synergy. Basically, Myriad makes extra copies of attackers (similar to Hero of Bladehold or Geist of Saint Traft), while Battalion creates a beneficial trigger when you declare three or more attacking creatures. Myriad doesn’t help Battalion, so it doesn’t make much sense why R&D would try to include both in a specific environment. But the interaction is not too confusing. It is grokkable and quick to explain. On top of that, it only ever comes up in a game if a player wants to attack with one Battalion creature and one Myriad creature. In any other situation, Myriad would have no relevance to triggering Battalion.

Instead, imagine playing a four-player game where every player has a few Miracle cards in their deck and tons of Cycling cards. Easy enough, right? You just expect a lot of Miracles at random times. What if you want to actually plan your strategy, or appreciate the scope of the nonsense in your game? Suddenly, you have to track whether every player has drawn a card yet on each player’s turn. Who cycled at end of a turn? Who cycled on another player’s upkeep? You also have to pace your own cycling decisions—during which two of your three opponents’ turns do you want to cycle in hope of Thunderous Wrath? How likely are you to cycle into another cycler? Do you need to conserve mana to do all this? Is anyone else in this game trying to figure this out? Did I leave my shower running? Should I keep playing this game?

The bottom line is this: readily-available instant-speed card draw makes the Miracle mechanic oppressive. (Miracles are brutal enough already.) Remember when they banned Sensei’s Divining Top in Legacy? And that’s just with two players! How is that less confusing that parsing the rules interaction between Myriad and Battalion? If you can explain that well, maybe you passed the GDS3 multiple choice test!

Carrie O’Hara is Editor-in-Chief of Hipsters of the Coast.