After a decade, it’s time to admit that I am the Dreamblade economy.

Dreamblade, for context, was Wizards’ entry into the world of miniatures, back in 2006. It lasted just over a year before Wizards put it on the chopping block after five sets (with a sixth having finished design and development). Dreamblade failed for several reasons, including the cost of production (oil peaked that year at $67.71 a barrel, compared to last year’s $49.41 peak or 2017’s startling low of $25.52), the payout of tournaments, and, less quantifiably but more relevantly, the cost of boosters and audience burnout. Dreamblade sets rolled out at the same rate of Magic sets—three a year—but were $14.99 ($18.64, adjusted for inflation) for a blind box of seven random figures. In other words, drafting Dreamblade was a fifty dollar ordeal and building a tournament-ready band of miniatures cost several hundred dollars—assuming you could find easy trades for your duplicate figures, many of which were bulk. It was popular for tournament grinders, though (including with Magic luminary Sam Black), and so when it died, there was a massive fire sale online. I went, over the course of several years, buck wild on those cheap figures.

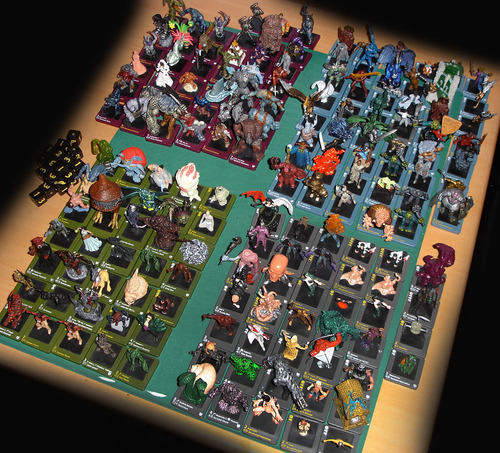

I thought the days of Dreamblade deals was over—over the last decade, I’ve tried to complete my collection (a “playset” in Dreamblade is three figures), but pickings have gotten slim, as I’ve bought up the easy targets and general attrition has taken out others—until last weekend, when I walked into a consignment shop/bookstore and found a Rubbermaid container overflowing with them. The word to describe my reaction was, according to my fiancée, who was present, “a squawk.” The rush of excitement I felt at getting a deal on these ‘blades, on potentially completing my collection, was immediate and intense, and I don’t know why. I play Dreamblade maybe twice a year. The other three-sixty-three days of the year, they sit in cardboard boxes in the guest bedroom. The cat parkours off of them, I bark my toes on them, and I periodically think about culling the rare figures and some optimal “warbands” and jettisoning the rest. I’m not going to do it, of course: my costs are sunk and I have made a quiet place for this zombie game in my life. To get rid of it is to admit defeat. To let go of Dreamblade is to accept that I’ve been suckered into an acquisition game.

This week, Twitter account da share z0ne announced a Kickstarter to fund their game, “The Devil’s Level.” Thirty second rundown on da share z0ne: it’s one of those self-reflexive, alt-comedy pages that uses the language of “low” culture ironically, in this case, “badass” tropes (skeletons, flames, metal typefaces) juxtaposed with absurdly mundane captions about social anxiety and splattered with gaudy watermarks. Some representative examples follow here, here, and here. The authorial voice fuses “relatable” with “alt-comedy,” and so the same sorts of people who can talk about “the meme economy” tend to enjoy dsz. Those people funded their Kickstarter to create an analog card game within 24 hours, with the base game selling for $27. For further context, I’d recommend reading this Motherboard interview with the “admin” persona—it draws in a lot of the other old guard of Internet 2.0, including the Toothpaste for Dinner/Kompressor/Natalie Dee crew, @dril, and KC Green.

Maybe the game will be excellent. More likely, it’ll be another Exploding Kittens—entertaining after a few drinks, something to bring out periodically when you have people over, but ultimately a Thing. An artifact. A box you have to find a place for among your other boxes. The issue is that games like Exploding Kittens and Epic Spell Wars of the Battle Wizards can’t be critiqued at the depth with which we’re able to critique Magic or Cuphead or PUBG. The choices made are shallower, the aesthetic less defined. They’re not games that grow, just games that get more complicated. They can’t be analyzed; they can only be either played or displayed. To me, then, these aren’t games in the strict sense—a series of operations uses defined resources that offers an outcome where one player/entity wins—but artifacts. These aren’t meant to live in ludic spaces, but to take up space in our lives, to fill or check boxes.

Last weekend, I went to a mall—the ultimate consumerist box—for the first time in approximately a decade. They had a Starbucks, and I was asleep on my feet, so I ducked in—through the food court, past the kiosks of aggressive salesfolk selling emoji stress balls—and was alienated by the entire experience, but by nothing more than the store that seemed to be nothing but Funko Pop figures. Now, in the abstract, there’s nothing much separating Funko from Dreamblade, other than the minor utility of a game system, but there’s something so confrontationally consumerist about Funko Pops. “Buy me.” they seem to say. “Display me. Box me up and move me to your new place when you go. I represent something that means a great deal to you. Collect me to prove you watch the right things.”

It made me think about one of the waypoints of closure, of going through a loved one’s boxes of detritus after they die, of how our memory eventually becomes an iterative process of letting go of various items of diminishing importance. Keep a shirt to sleep in, keep their favorite books, but at what point do you become the museum docent, rather than the bereaved? When do space constraints supersede nostalgia? When do we reach the threshold at which we finally have enough?

How many little plastic figures of ogres and wraiths do I need before I feel that surge of joy I used to feel as a kid, that joy I haven’t felt since my disorders started manifesting?

To be less specific, I wonder how many $10,000 collections have been sold for $50 at estate sales after sitting in attics and under couches. My loved ones will know how important Magic was to me, but, as non-players themselves, will they cherish my box of Eldritch Moon draft picks with the same gravity—or lack thereof—that they handle my foiled-out Commander deck? When you’re gone, there’s no one to track the spike of Gorilla Shamans and feel pride in your smart pick. Will anyone track the metagame or commiserate about bad preorder picks or watch the MTGO economy, or was that only your way to interface with the game?

I am the Dreamblade economy. I finally admit it. Like all economies, it’s built on waste and rapacity and the ceaseless tidal surges of chemicals that tell us to acquire, to consume, to squirrel away for leaner years. Like all economies, it will all fail one day, and those in the future will laugh about tulip crazes, about bitcoin frenzies, about the price of snails, about my redundant Dreadmorph Ogres. In the meantime, roll ‘em if you got ‘em, chase Pauper value, keep an eye out for rare Funko Pops, and if someone tells you it’s a bubble, at least there’s air enough to breathe in here for now.