Let’s get political—briefly, I promise. This is a picture of the Oval Office under the previous administration:

(Photo c/o White House Historical Association)

This is the Oval Office in early September, after its most recent round of renovations under President Trump:

(Photo c/o Carolyn Kester /AP)

Those military flags were installed by the current President to send some kind of message—the content of which I don’t consider worth speculating on, and the optics of which I don’t want to analyze. It’s another datapoint in the endless galaxy of insecurities that make up the man and, after two years of this, I don’t want to talk about what his insecurities represent any more. I do think, though, it’s worth talking about what flags alone can represent.

Flags are—well, flags are fraught. There’s an assumption of identity tied up in a flag; you become the bearer of a nation’s development on your shoulders when you wave the flag. To many, a flag is a signifier, nothing more: people who buy American flag Chubbies and wear Union Jack t-shirts during the World Cup. But to an even larger set of the population, a flag is a definition: I am American, and so I respect the flag. I respect the flag, and so I am American.

At their simplest, flags are a tool designed to claim territory and direct attention—separating a chaotic battlefield into consumable information, delineating ambassadorial delegations, etc. In this form, flags are nothing more than a source of information that becomes a rallying point—a place of safety, a point of connection. Flags are also a symbol of power, of colonization or retrenchment. A flag is a promise to back up assaults with martial action.

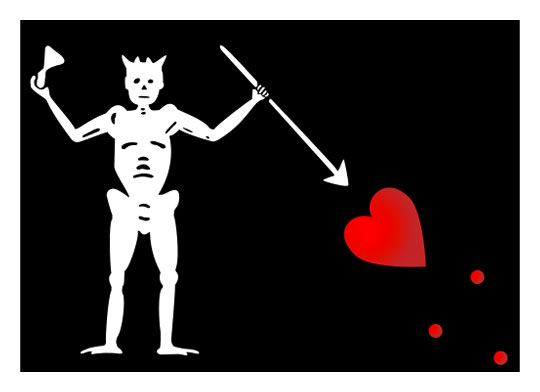

On that level, flags are a warning—think of the sinister black flag eighteenth-century pirates would run up the mast as they closed in on freighters. One of the flags with the longest lineage, the original Jolly Roger (probably from a common colloquialism, like calling a flag “Scumbag Steve”), wasn’t just an instrument of terror but a semiotics lesson. The original—the skull and crossbones version popularized in culture—was flown by Emanuel Wynn as he raided the colonies of the Carolinas in the first decade of the 1700’s and included not just a promise of death in the skull and crossbones, but a shaky hope for leniency for immediate surrender in the hourglass. Over the years, other pirates adapted the flag. Here’s the version that some early 18th century pirates used (you’ll also see this referred to as “Blackbeard’s design,” which is probably inaccurate but, speaking from firsthand experience, irresistible to tourists):

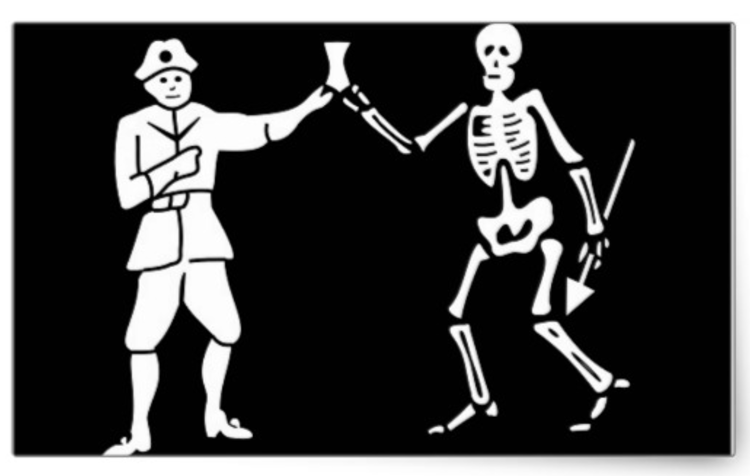

Ironically, I’d consider this a step back, iconographically speaking. That Wynn flag—black flag, skull and crossbones, hourglass that emblemizes mercy but also suggests venom and volatility—is a masterpiece. The Jolly Roger above is anatomically confusing, compositionally imprecise, and overly busy. In comparison, here’s my personal favorite, flown by—and caricaturing—Bartholomew Roberts. Look at this jolly dude! Behold how slipshod the design is! This is the shitpost of pirate flags.

These flags, like many others, are an exercise in branding, a reduction of a promise—“We are the dudes who steal your belongings and murder you”—to a simple icon. More than anything, though, it was a way to capitalize on the pirates’ reputation: by running up the Roger after flying under false colors, it encouraged enemy ships to surrender immediately, seeking mercy, rather than fight to the death. Thus, a flag with a legend behind it saved lives on both sides. Pirate flags, like all flags, also carry with them an implicit threat: I’ve got something larger than the both of us that has my back, whether it’s a pirate crew or a major economy.

There’s historical similarities between pirate vessels raising the Jolly Roger and the insignias marked on the wings of bombers flying low over Laos or the flag ISIL flies, which warps the black standard of the Quraysh, the tribe to which the Islamic prophet Muhammed belonged. Flags are about evolution—observe the evolution of the Jolly Roger to the “extreme” try-hard-ism of the Sea Shepherd flag and various Myrtle Beach bumper stickers—and they sometimes carry with them the history of the country, or the history of a subset of the country’s population, bound up in the cloth.

Magic’s first flag was the Orcish Oriflamme, whose pretentious alliterativeness contrasts the simplicity of its mechanic: those who fight under the banner are stronger and more motivated. You’ll see this reflected in Exodus’ Coat of Arms, which further develops the flag imagery to go beyond a nation and make it more specific, to a family. Boosting your creatures is a common theme in Magical flags—Konda’s Banner, Leonin Sun Standard, etc. It’s also pretty simplistic and deals with the metaphysical benefits of patriotism being transliterated into physical benefits, which is pretty poor design.

I’d argue that Magic’s premier flag-related mechanic was the Flagbearer triad from Apocalypse. Coalition Honor Guard got reprinted for Eternal Masters. If you’ve ever played against these guys, then you know how frustrating they can be—like if Spellskite was common and its ability was free. There are plenty of flags in Magic, certainly—as in the Khans of Tarkir tri-mana flag cycle—and their are flag-like signifiers aplenty: what are the Ravnica guild marks or the Kaladeshi rebel graffiti if not a sort of symbol of community and enforcement? I find the flagbearer mechanic an interesting one—it suggests the chaos of real warfare, it underlines that the most vocal and patriotic are often the most easily targeted.

Apocalypse is, in the scheme of things, ancient. It came out three months before the World Trade Center fell, the year that American flags began flying from H2’s and grocery stores. It came out before many of us could point to Afghanistan on a map. But even with seventeen years of perspective, I think the flag bearer mechanic is the one that best embodies the use of flags: it doesn’t boost you, it rallies you. It marks but does not make you.

There’s an American flag on the moon. There are flags that fly from car lots in grandiose, football-field-sized and silken versions. (Preliminary research shows these tend to run about $1,300-$1,500, in case you were wondering.) There are flags on our football uniforms, our license plates, our schoolyards. Our countries are branded; our lives are flagged. If nothing else, it does us a service to consider what that omnipresence means. To me, it means we carry a portion of our nation’s history, shrouded in a bit of cloth. It means we belong, and we are marked, and we are all, in our own way, the bearers of a flag.

A lifelong resident of the Carolinas and a graduate of the University of North Carolina, Rob has played Magic since he picked a Darkling Stalker up off the soccer field at summer camp. He works for nonprofits as an educational strategies developer and, in his off-hours, enjoys writing fiction, playing games, and exploring new beers.