Welcome to the Best of Hipsters of the Coast Week as we revisit some of the top articles we published this year. There will be some new content this week but for the most part we’ll be taking a look back before we kick off the new year. A Planeswalker’s Guide to Earth is the brainchild of Curtis Wiemann, a student of Earth history who enjoys taking the worlds of the Magic Multiverse and deconstructing the earthly influences that Wizards’ creative team draws upon for you. Below is the first part of Curtis’s phenomenal look at the Mayan culture’s influences on the world of Zendikar. When you’re done, make sure you check out part two as well.

In this week’s Uncharted Realms, we conclude Jace and Gideon’s search for allies back where their quest began: the embattled plane of Zendikar, the backdrop to the upcoming set. In this week, A Planeswalker’s Guide to Earth will explore some of the historical inspirations and analogues for the cultures, landscapes, and themes of Zendikar. As this column began on Tarkir with an introduction to the medieval Mongol history and culture that inspired the plane, it will now continue on to Zendikar and look at its close analogue on Earth – the Mayan civilization and legacy of the Yucatan Peninsula.

In his articles and podcasts regarding Zendikar, Mark Rosewater mentions that the block and plane were the result of bottom-up design rather than top-down, as was the case on Tarkir. Rather than the fantasy of a plane inspiring the mechanics and cards of its set, on Zendikar the mechanic came first – “lands matter.” As such, there is no single source from which the plane’s cultures and landscapes draw inspiration, but consciously or unconsciously, Zendikar echoes the religious monoliths, physical geography, and thematic content of the Mayan civilization, which held sway primarily in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula for almost four thousand years.

Land Matters

At its most basic level, Zendikar has a great deal in common with the climate and geography of the Yucatan, at once lush and unforgiving. Unlike the pine and oak forests (or their magical equivalents, I guess) we see throughout Theros, Innistrad, and other planes which draw from European medieval themes, the dominant flora of Zendikar appears to be moisture intensive tropical plants and trees, from the depths of vine-choked [casthaven]Verdant Catacombs[/casthaven] to the canopy of the [casthaven]Misty Rainforest[/casthaven]. Mayan civilization flourished from at least 2600 BCE in what is still today one of the largest contiguous tropical rainforests in the world. The flat, humid forest landscapes of Bala Ged on Zendikar are not so dissimilar to the Yucatan tropical rainforest, heartland of Mayan civilization.

Even without trap-riddled tombs and temples, the landscape of the Yucatan peninsula held both perils and treasures for the peoples who settled there nearly 5000 years ago. Covered in dense jungle foliage and populated by hostile predators and potentially deadly mosquitoes, the Yucatan rainforest was extremely hazardous for early settlers from the Mesoamerican cradle of civilization (and deadly for many later European invaders).

The flat, humid forest landscapes of Bala Ged on Zendikar are not so dissimilar to the Yucatan tropical rainforest, heartland of Mayan civilization.

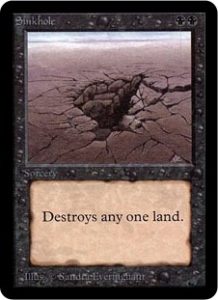

Furthermore, for such a tropical environment, the Yucatan is unique for its lack of above-ground freshwater. Most standing water in the peninsula is located to the northern half of the rainforest, in the form of undrinkable marshes like the swamps of Zendikar’s Guul Draz region. Mayan civilization, like cultures around the world, was formed around the sources of water available in this singular landscape – the cenote sinkholes, which provided access to a vast underground sea. These sinkholes, vital to sustain wide-scale agriculture (as well as providing basic, fundamental drinking water), were held as sacred by the Mayan people and formed the basis for the greatest cities of their civilization.

Temples of Forgotten Gods

Following an initial period of settlement and growth from about 2600 BCE onwards reflected in the archaeological record, Mayan civilization bloomed in the Yucatan. From about 750 BCE to 250 CE, the Maya raised a series of massive cities, each the center of their own political state and dwarfing their contemporaries in classical and medieval Europe. Major urban centers included the rival city-states of Tikal and Calakmul and the metropolas of Copan to the southwest.

During the classical period of 250-c.900, the Maya made incredible discoveries in astronomy and mathematics, postulating the mathematical concept of the numerical zero, constructing a temple series to correspond to the solstice and equinox, and inscribing a 28-day lunar calender which extrapolated all the way out to present day (and then very much concerned people by its abrupt end this last year).

The monumental architecture of the Maya, constructing in the same limestone that made up the uniquely porous landscape of the Yucatan peninsula, is testament to their religious beliefs and artistic innovation as well as the social organization necessary to raise such structures. Although religious and political statuary and architecture dominated the centers of the ancient cities of the Maya in vast temple complexes, the private homes of the elite still showcase murals, ceramics, and (very rare) written works which illustrate the breadth of Mayan culture and achievement at its height.

Then, around 900 CE, the end of this vibrant world came with a shocking swiftness.

The societal collapse of the Maya in or around 900 CE remains a mystery, even to the extent that it occurred at all. A recent history of the subject (Richardson Gill’s The Great Mayan Droughts) categorizes a staggering eighty-eight theories of what may have happened to the architects of the Yucatan’s vast cities, ranging from external invasion, to internecine warfare, to disease, to dramatic drought and climactic shift.

Land matters, to the ancient Maya and people of Zendikar alike.

Whatever the case, however, the result could be seen to varying degrees throughout the Yucatan. Much of the ambitious city expansion of the Classical era halted abruptly. While many of the older cities still stood, their populations appear to stagnate or shrink according to the archaeological record.

It is this image – albeit a little more dramatic than the historical record – that most closely resembles the world of Zendikar before the Eldrazi. Despite massive architecture, the temples to misremembered gods, which dominate the landscape of the plane, most of the peoples of Zendikar live in relatively impermanent conditions in the shadow of these great structures, poised to move with the dangerous whims of the landscape. Land matters, to the ancient Maya and people of Zendikar alike.

The landscape of the Yucatan, with its dense jungle and life-giving cenotes, is as unique and magical, dangerous but full of hidden succor, as the tropical panoramas of Oran-Rief and Bala Ged. The Mayan people themselves, in the wake of a likely-environmental catastrophe, saw their civilization recede according to the very will of their environment, and were left in the centuries that followed surrounded by the religious architecture of previous generations. Perilous and beautiful, home to ancient temples and ruins, the Yucatan of the 10th century echoes the landscape of Zendikar, the once and future setting of Magic’s plot.

Join me again next week, when we’ll look at some of the cultures of Zendikar and their relation to Mesoamerican society.

Curtis always invites you to leave a comment! But sometimes he doesn’t get a notification and misses them, so he’ll check back.