In this week’s Uncharted Realms, Nissa continues her fight against the Eldrazi. Even without her connection to the plane of Zendikar and its empowering leylines of natural energy, the Planeswalker cannot sit idly by as her home is overrun by monsters. After fighting a desperate battle against a stampede of lesser Eldrazi spawn, Nissa realizes her goal: to rediscover the wild spirit of her plane and its mana at the sacred sanctuary of Khalni Heart.

Pilgrimage and Hermitage

In previous weeks leading up to the Battle for Zendikar, this column has looked at pilgrimages – like the path of Ulamog’s misguided followers – as solemn journeys to a sacred place defined by religious belief. Sometimes, however, this arduous expression of belief was not enough for the peoples of the medieval period. For some who, like Nissa, had lost their sense of spiritual connection in the midst of a harsh and calamitous world, only a return to nature would suffice

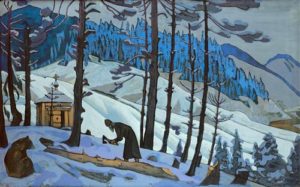

Such a path was destined for a young man named Bartholomew of Radonezh, living in Russia under Mongol rule in the 14th century. After caring for his ailing parents until their death, this deeply religious man gave away all his possesssions to his extended family and journeyed deep into the Russian [casthaven]taiga[/casthaven], first with his elder brother, and eventually alone.

For years, Bartholomew lived in solitude, travelling “in search of a wilderness.” The later official account of his life and sainthood would claim “he saw the trials of the desert: the lonely rigorous life, the poverty and privations which must be undergone, since food, drink, and the bare necessities of life were nowhere obtainable… only the forest stretched out on every side, and everywhere was wilderness.”1 It was only years later that other monks would follow after him, building a monastic community around the reluctant hermit and acclaiming him their leader, Saint Sergius of Radonezh.

Figures like the Saint Sergius were rare, but inspired awe by their example. In the Abrahamic tradition, however, this retreat into “the desert” was not exactly new. Prophets from Moses to Elijah had found inspiration amidst the wilderness, and had returned to their followers to impart divine wisdom. Both Jesus and Muhammad were credited with a period of hermitage, where they went into the desert to better commune with God. Both were tempted and overcame temptation, proving their devotion to their message despite hardship and isolation.

What exactly Sergius and others sought in the forests, deserts, and untracked wilds of the medieval frontier is not known. But they made abundantly clear what they wanted to leave behind.

[casthaven]Journey to Nowhere[/casthaven]

The 14th century Russian world of St. Sergius was not so dissimilar to Nissa’s Zendikar – torn by war, cut off from its roots. In the generations prior to the saint’s birth, the Mongol Empire had overrun the Orthodox principalities that ruled much of what is today Russia, and established the Golden Horde to gather taxes and assert control over their new subjects. The traditional centers of Russian culture and religion in Kiev and Novgorod were sacked and would take years to rebuild. Only Moscow, then just a second-tier city to the north, was spared for immediately and completely surrendering. Thousands of Russian nobles and peasants alike had died in battle or in subsequent famine.

Worst of all, the clergy of the Russian Orthodox Church had lost their connection to the hierarchical head of their faith. The Patriarch of Constantinople, head of the Orthodox Church at the time, was inaccessible, cut off by the forces of another Mongol army – the il-Khanate to the south. Without the structure of their faith, many Orthodox clergy despaired, and took the Mongol invasion as a just punishment for unknown sins.

Whereas a pilgrim wanted to go to a holy place, a hermit might simply want to get away from an unholy one.

Admist this and similar climates of war and hardship, Sergius, Moses, Nissa, and countless other hermits sought refuge and enlightenment in the wilderness. Unlike a pilgrimage, undertaken to reach a holy destination and participate in the community of one’s faith, hermitage was intended to be solitary, solemn, and alone. A hermit was drawn as much by the promise of the unknown hardships of the desert as they were by the known horrors of the world in which they lived. Whereas a pilgrim wanted to go to a holy place, a hermit might simply want to get away from an unholy one. And each hermit ultimately faced their hardships alone.

Some, like the major prophets Muhammad and Jesus, found and overcame temptation in the desert, proving their devotion. Others faced deprivation, poverty, and fear. Moses was awestruck and terrified by the burning bush, but Sergius must have felt the selfsame terror with every lengthening night in wintertime, knowing how cold his Siberian home would become, how alone he was in the wilderness. To survive and endure as a hermit was to lay an unshakeable claim to faith, tested in harsh conditions in the absence of social expectation and peer pressure.

Nissa, like hermits throughout history, is leaving behind a world of strife, but she likewise is not going forward into contemplative peace. In the wilderness now she seeks a connection that is lost to her on the battlefields of the Eldrazi invasion or even the camaraderie of Gideon’s camp. Whatever her contribution to the battle against the Eldrazi will be, it will be shaped by her own, individual connection to her world, as personal and vital as the faith of countless others who journeyed in search of the unknown before her.

Curtis is a city planner and wayward historian up in Massachusetts.

1 Epiphanus, “The Life of Saint Sergius,” 120.