In this week’s Uncharted Realms, we’re still on Zendikar, but focusing upon a very different war against the Eldrazi. Drana, Bloodchief of Malakir and sovereign of Zendikar’s vampiric civilization, leads a fighting retreat against a vast otherworldly host. With victory and even survival a distant hope, she receives an unlikely ally in the form of a party from the allied forces of Gideon’s coalition, and with their help (and her own ruthless tactics) she obliterates her Eldrazi pursuers and makes for the encampment at Sea Gate.

The art and cards in Battle for Zendikar, which now has its full spoiler online, have a common theme of strange alliances faced with the threat of the Eldrazi:

Before the emergence of the Eldrazi titans, Zendikar had rival factions and nations, species and cultures at war with one another for the pockets of safe land on a turbulent plane. Now, faced with annihilation by a vast and terrible foe, the disparate peoples of Zendikar are banding together, illustrated at its most stark by the alliance between the kor and vampires in the week’s Uncharted Realms.

Desperate Times and Desperate Measures

Alliances of sworn enemies against a greater threat are common throughout human history on Earth. Probably the best known and most pivotal in recent history took place during the course of World War II, where the Soviet Union first signed a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany and its fascist allies despite its own socialist ideology and Hitler’s stated racial antipathy for Slavic peoples and territorial ambitions for Soviet territory.

Following Germany’s surprise invasion of Russia in June 1941, the USSR made common cause with the Allied forces, including the United States and the United Kingdom, both of whom had politically or militarily opposed the rise of the Communist regime in Russia. The course of history following the fall of the Axis powers bears out just how fragile this unlikely alliance was, as offensives near the end of the war showed the United States and the USSR jockeying for territory and power in preparation for the impending Cold War.

From left: Winston Churchill (PM Great Britain), Franklin Roosevelt (President United States) and Joseph Stalin (Premier USSR).

Faced with the triumph of intractable political ideologies (like fascism and democracy) or economic systems (such as communism and capitalism), it seems natural that perhaps some strange alliances would form to overcome a perceived greater foe. But occasionally unusual alliances came into being where a simple power imbalance forced would-be rivals into the same camp. European history in the 19th century showcases a number of fragile alliance systems which came into existence – mostly in the hopes of preventing an all-out conflict like the World Wars from the following century.

For centuries since its conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the Ottoman Empire had been positioned as the greatest external rival to the Christian powers of medieval and imperial Europe. From 1529 to 1698, the Ottoman Empire intermittently drove northeast from Istanbul to Vienna, conquering the former Byzantine territory of Greece and Hungary and arriving at the gates of the Habsburg capital.

For three hundred years in total, the forces of Christian Europe allied behind the Habsburg dynasty against the Ottoman Empire, and would then go back to fighting one another, once a given offensive concluded. This dynamic only ended with the Crimean War in 1853, when all of western Europe banded together again – but this time, it was to support the Ottoman Empire against the rising power of Russia. The motivating concern behind these strange and fragile alliance systems was the fear of a single superpower eclipsing all others – so great was this concern that nations could overlook former conflict and rivalry in the name of their mutual self-interest.

Better the Devil You Know…

Perhaps the greatest example of unlikely allies in the face of external threat came in the midst of the religious wars in the medieval Crusader States. The Crusader States, which at their height included Jerusalem and other cities in modern-day Syria, Israel, and the wider eastern Mediterranean, were established in the wake of the First Crusade in 1099 and held until 1291. For two hundred years, Frankish Christian knights and colonists existed in a near constant state of war with the surrounding Muslim sultanates, who viewed the Crusaders as interlopers in the dar al-Islam. A lasting peace between sides was unthinkable, given the fundamental convictions of the Franks that the holy sites of the Eastern Mediterranean should be Christian and Christian alone and their willingness to enforce this dictate by wholesale slaughter.

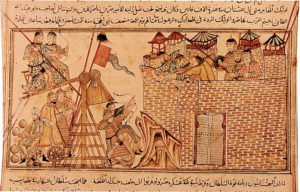

Near to the end of their reign in the eastern Mediterranean, however, the bitter conflict between Islamic and Christian powers was overshadowed by a vast and incomprehensible threat. “For our sins,” the Crusaders heard from Russia, “unknown tribes come.” By 1255, the Crusaders were aware of an army of Mongol tribesmen, led by fierce warlords, who had toppled powerful empires to the far north and east. Travellers and spies reported that Muslim Persia under the Kwarismian dynasty was utterly destroyed, and armies of Mongol horsemen had sacked Baghdad, putting to death the caliph from the line of the Prophet.

Mongol besiegers in a Muslim chronicle. The capture of Baghdad in 1258 would not be repeated by a non-Muslim force until the presidency of George W. Bush.

Many Crusaders rejoiced at the news of their rivals’ defeats at the hands of an external foe. Crusading leaders from St. Louis IX of France and King Edward I of England made entreaties to the Mongol Empire, hoping to learn of their intentions. To the north, some Christians had even allied with the Mongols, sacking Damascus and converting the Great Mosque there into a cathedral. But the leaders of the Crusader States were wary. The Mongols had shown no mercy to their foes from Russia to Persia, regardless of their political or religious background.

Soviet policymakers, Habsburg royals, and Crusading leaders alike ultimately decided for one fundamental rule: better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.

As the Franks debated, an incredible opportunity fell into their laps. Sultan Qutuz, ruler of the Mamluk dynasty of Egypt, made an entreaty to the Crusaders. The greatest enemy of Frankish Christianity in the Eastern Mediterranean, whose dynasty was founded in part because their predecessors had not done enough to end the Crusader States, now offered an alliance against the common threat of the Mongols. After debate, the Crusaders accepted his offer, allowing the Sultan free passage through their lands to assault the Mongol armies across their territory in Galilee. With this transit (and thanks to some internal chaos in the Mongol Empire at the time), Qutuz was able to meet the Mongol army at Ain Jalut and defeat them entirely, ending the threat they posed to Egypt. Within weeks of this short-lived alliance, the two forces were at war again with one another.

Whether involving nations in the Second World War, imperial powers in 19th century Europe, or religious dynasties in the 13th century Middle East, desperate times bred desperate measures and made for strange alliances throughout our history. In the end, however, the circumstances were not too dissimilar to those from this week’s Uncharted Realms (but for the presence of big tentacled monsters). There is no love lost between Drana and her kor allies – they band together solely to defeat a more monstrous foe, an enemy whose victory would mean the end of the balance of power they all relied upon as normal. The same could be said for any of the uneasy alliances throughout this brief historical digression. Soviet policymakers, Habsburg royals, and Crusading leaders alike ultimately decided for one fundamental rule: better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.