In this week’s Uncharted Realms, we visit the planeswalker Chandra Nalaar on Regatha, where she continues to practice pyromancy in Keral Keep, the monastery dedicated to the teachings of Jaya Ballard which took Chandra in after her explosive departure from Kaladesh. Although she struggles to carry out the ritual chants and quasi-religious duties of monastic life, Chandra shows prodigious talent as a fire mage, earning her the close tutelage of the monastery’s abbot and promotion to his seat following his death. Despite her misgivings, and the efforts of Jace and Gideon to recruit her efforts against the Eldrazi, Chandra agrees to take up the abbot’s mantle and with it the spiritual and magical leadership of her Regathan home.

Monasteries and Monks

As central to the medieval European landscape as its walled castles and sprawling farmlands, the Christian monasteries of the pre-Reformation era defined culture, learning, and religious life in Europe and Orthodox-Byzantine Asia for centuries.

A monastery was (and are, today) a center of religious contemplation and education, set apart from the concerns and distractions of the mundane medieval world. Unlike a village church or magnificent cathedral, these were not places for lay worship primarily. Instead, a Christian monastery was intended as a secluded community of the faithful, populated by clergy of the Orthodox or Catholic Church dedicated to a discipline of religious rigor that defined their scholarship and daily life.

In a society otherwise motivated by fundamental concerns – like producing enough food to stay alive – monks and nuns in the medieval monastic tradition were aloof from earthly life and exempt from levy and tax in nearly every circumstance. In exchange, monastic communities provided scriptural education (to those inducted to their number), religious leadership, and intangible spiritual benefit by means of prayer for the souls of the deceased.

A monastery was a center of religious contemplation and education, set apart from the concerns and distractions of the mundane medieval world.

Often founded by noble donation and funded by their own economic activity bolstered by their freedom from taxation, monasteries flourished in the medieval Christian landscape. The first monasteries throughout the Roman Empire were likely communities who hewed closely to the communal teachings of Christ and sought to recreate a closely-knit fellowship in the example of his disciples. Following the acceptance and spread of Christianity as the dominant European faith of the medieval period, these religious communities in the Catholic tradition frequently owed their inspiration to a specific saint in the religious canon, following their teachings and example much as the the monks at Keral Keep seek to emulate Jaya Ballard, Task Mage.

St. Augustine of Hippo (354 CE – 430 CE), St. Benedict of Nursia (c. 480 CE – 543 CE), and St. Francis of Assisi (1181 CE – 1226 CE) each inspired influential monastic communities in their example in the Catholic faith. In life, each recorded their philosophy upon a Christian life in accordance to Scripture, and these were codified as the guiding rule of the monasteries founded in their honor, each with a slightly different perspective upon maintaining connection with the Lord and His Gospel.

St. Benedict’s guiding motto, for example, was “ora et labore” – pray and labor. Benedictine monks believed physical work and spiritual contemplation to be inseparable, and strove (now as then) to combine a life of prayer with labor for the Christian community. Others, like the Franciscan Order, focused upon a vow of poverty in conjunction with spiritual contemplation, such they were often associated with begging rather than the working approach (and accumulation of material possessions) undertaken by their Benedictine brethren.

A World Apart

Whatever the guiding rule of a medieval monastery, they played a variety of spiritual and mundane roles for the faithful of a Christian community. First, and most importantly for their noble sponsors and the devout laity, they were presumed to benefit the souls of the Christian dead, praying for the forgiveness of their misdeeds and their entrance into Heaven. Sin and its resultant punishment weighed heavily upon the minds of Christian peoples in the medieval era. Without the benefit of honest confession and last rites, one’s soul was in mortal danger of languishing in Purgatory or condemnation to hell.

Incidentally, this guy as a Acolyte of the Inferno is a religious devotee of Hell, according to Christian wording a la Dante. SATANIST MONKS?!

Much like the ancestor worship practiced by the Temur and animists of the Asian steppes, monastic prayer allowed for the chance to venerate the dead and potentially spare them suffering in the afterlife by praying for their release from punishment. Many monasteries owed their sustenance and growth to donations intended to establish praying orders or chapels for their illustrious ancestors, while these same concerns motivated more humble donations from the general public. Chandra’s fellow monks share this oratorical focus upon chanting or praying with their earthly counterparts from our own history.

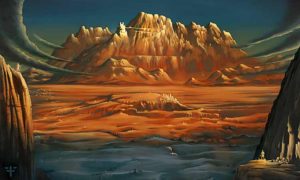

Plenty of Christian monasteries were built in remote settings like Keral Keep here. Some, especially in the eastern expanse of Russia, continued Orthodox traditions of hermitage in complete isolation.

In addition to these more esoteric aims, medieval Christian monasteries endured as a rare source of educational opportunity in an otherwise scarce intellectual landscape. The monastery was one of the few places in Christendom dedicated to education left in the vacuum of Rome’s collapse, and it is no surprise that most of the chronicles of medieval events and history were written by monks or knights with religious tutelage. There was little opportunity or impetus for secular centers of learning which existed in Greek and Roman tradition, but monasteries preserved and disseminated a great deal of their philosophical and intellectual work, interpreting them where they could be seen to intersect with the given truth of the Christian Gospel.

Monasteries were as much centers of learning and contemplation as they were conservative bastions of tradition and established canon.

Ultimately, however, as Chandra no doubt feels in Keral Keep, the monastery was a place that revered tradition, continuity, and isolation to a possible extreme. Founded by saintly example, guided by religious rule, intentionally isolated from earthly concerns, and given to interpretation upon strict religious lines, monasteries were as much centers of learning and contemplation as they were conservative bastions of tradition and established canon. Chandra’s monastery is a great (and extreme) example – her fellow monks venerate Jaya Ballard and lionize her teachings, but most of her actual quotes are little more than pithy boasts and snappy one-liners. Whatever her misgivings about the traditions of Keral Keep, however, Chandra for now has chosen the same departure from the distractions of the mundane world as did countless members of religious orders on Earth, focusing upon her role in the monastery rather than leaving with Jace and Gideon. Time will tell whether the decision helps her grow as a planeswalker and leader, given time and isolation to learn and practice, or dooms the efforts of her allies against the monstrous Eldrazi.