In this week’s Magic fiction, published as part two of the previews for Magic: Origins, we get to see the backstory of Liliana, Shoddy Heretical Healer on Dominaria sometime long before the events of the recent sets (Fate Reforged excluded, perhaps). After drawing upon dark magic in a futile attempt to save her brother Josu, Liliana turns her sibling into an unholy revenant, discovers her latent spark as a Planeswalker, gets old, and ultimately barters her soul to four demons in an effort to regain her immortality and youth lost to the Mending of the Time Spiral block. There’s so much to choose from this week, but we’re going to focus on the demonic forces behind her rise to power. Liliana’s story – and much of medieval belief surrounding magic – is inescapably shaped by demons.

Demonic Presence

Throughout the monotheist and polytheist religions of the medieval period in Europe, Asia, and Africa, demons exist as a constant reminder of the dangers that awaited unwary mortals and an inspiration for the evil forces of several of Magic’s planes. The oni of Kamigawa are a direct translation of Shinto oni in medieval Japan, bestial demons opposed by benevolent natural gods. One of the previous Planeswalker’s Guides to Earth touched upon the link between the Sultai rakshasa of Tarkir and the fierce Hindu demons of the same name. And the djinn and janni of the Arabian Nights expansion were based upon spirits of the same name invoked throughout the eastern Mediterranean world and rejected as demons by the faith of Islam. Across a diverse pantheon of spiritual beliefs, demons persisted as a perceived threat to mortal bodies and immortal souls.

For a religion devoted to a single God, early Christianity was convinced of a multitude of evil spirits that lived to assail His faithful. Demons were depicted only occasionally in the official Gospels and far more frequently through the canonical Apocrypha (texts that, while still considered valid, were not included in the final compilation that became the Christian Bible).

Across a diverse pantheon of spiritual beliefs, demons persisted as a perceived threat to mortal bodies and immortal souls.

According to (a pretty bigoted element of) Church theology in the medieval period, demons were born of Lilith, Adam’s first wife, shaped from river mud by God.1 Lilith believed herself to be Adam’s equal, as she was created concurrent with the first man, and her husband rejected her. Cast out from Eden, Lilith’s descendants by Adam became demons known as nephilim, dispatched against the faithful descendents of Adam and Eve (and used as four-color monsters on Ravnica). Christian faithful and Ravnican city-dwellers alike had good reason to fear nephilim, as they represented ancient forsaken beings that existed beyond the established order of society.

Beyond this designation, however, Christian demons were diverse and adhered to no single standard or origin (and were sometimes used interchangeably with devils). The Christian faith which came to define the social, political, and religious landscape of medieval Europe was born into a heterodox world of polytheist faiths, each with their own menagerie of spirits, gods, and entities to be praised or feared. Many of these entities were presumed to exist in early Christian belief, but were relabeled as demons according to the new divine order. As such, satyrs, djinn, and jackals (drawing from Egyptian sacred tradition) that existed in Mediterranean belief prior to the modern era appear as demonic forces in the Apocrypha, bridging the gap between polytheistic religion and Christian faith.2

Within Us and Against Us

With the development of the New Testament and the establishment of a complex and hegemonic Christian society, demons evolved to represent a new threat to the faithful – a threat Liliana, with her many debts, might recognize. Rather than simple assailants like the monstrous nephilim or bestial satyrs, demons became associated with possession and madness.

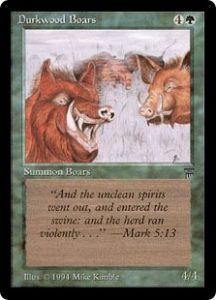

The most famous Biblical encounter with demons takes place in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and John. In the region of Gerasenes near Galilee, Jesus and his disciples met a man inhabited by a legion of impure spirits, who were so numerous that they called themselves Legion. At Christ’s command, the man was healed, and the demons inhabited a herd of swine, who plunged into the lake and drowned to escape divine retribution.

As the Bible went through successive translations and moved away from the animist influences of Mediterranean paganism, the image of demons (and the Devil) that emerges from the later editions of Christian holy texts are far more subtle, tempting the unwary and inhabiting the unfortunate. In addition to demonic forces like Legion that invaded and tormented, still others cajoled and misguided the faithful, appearing as angels to lead Christians to ruin or instructors teaching mastery of the dark arts. From Faust’s patron to the horned demons of Goya’s paintings and Salem’s witch trials, the theme of demons offering magical insight in exchange for the destruction of one’s mortal soul became a recurring motif in both popular and canonical perceptions of demonic power. Liliana’s Raven Man and Kothophed both adhere to this theme, and her deal with each turns out to be torturous at best and catastrophic at worst.

Rather than simple assailants, demons became associated with possession and madness.

The running theory behind this shift is that the concerns of Christian leadership shaped popular belief in demons through the ages, and those demonic creatures they describe embody the most dire threats to Christian society in each era.3 When Christianity was shaped amidst competing polytheistic religions in the Mediterranean world, it saw demons as external forces embodying foreign beliefs and spirits directly attacking the faithful. As the religion achieved cultural influence and power, however, its enemies became more insidious, an explanation for madness and temptation to evil among good Christian peoples. Amidst a landscape of walled castles and tended fields like Liliana’s home, the peoples of Christendom needed to be always alert for the enemy within their midst, whose temptation to the unwary could prove as destructive as any army, monster, or natural disaster. In medieval Christianity and Magic’s multiverse from this week’s article, the true power of the demon is to lead a single soul astray, a threat to any person from peasant to Planeswalker.

1 Robert Newton, “Demons.” (North American Review, Nov.-Dec. 1995), 44.

2 Pre-Christian Greek religion was extremely influential to the early Bible, which was written and promulgated in Greek and therefore used Hades in place of Hell as well as satyrs for demons. So similar were the two theologies that when the apostles preached to Greek worshippers, they were confused with priests of Hellenic paganism in Acts 14:12.

3 Newton, 48.