Last week, the Project: Lightning Bug Uncharted Realms article brought us back to the urban plane of Ravnica, where we learned a little bit about the medieval city and its foundation by charter. This week, we look at guilds themselves and the role they play in Ravnica and throughout medieval Europe.

Gold, “Gilde”, and Guilds

As was mentioned in last week’s article, the walls and charter of a medieval city denoted a measure of freedom from the established order of feudal society. This is not to say that a common miller could claim the same social privilege as a noble squire or clergyperson. Parentage, social rank, and hierarchies of race, gender, and religion still more-or-less applied in the growing cities of Christendom as they did in the surrounding countryside.

But without the direct relationship between landlord nobility and tenant peasantry, the new class of craftpeople, merchants, and wage laborers who flocked to medieval cities stepped outside the normal power dynamic that defined medieval feudalism. Without working the land to pay the noble class, peasant city dwellers did not owe the same service and payment to knightly protectors as did their agricultural counterparts. This meant, however, that they did not enjoy the same protection and leadership afforded by a noble ruler. Some other form of social organization for common defense had to take its place.

Like the kraken, our first mention of the word “guild” (or “gild”) comes from the North Sea. In around the eight century CE, the Danes refer to “frith-gilds” in the historical record. Loosely translated as “peace guilds”, these communal organizations were formed in Danish towns to establish public order and to issue summary judgment upon violent offenders. Members of the guild paid dues, organized public feasts, and donated to the poor, in addition to their peace-keeping duties. It is thought that the term “gild” referred to the financial aspect of group membership, but is is also held that the groups were closely associated with, and named for, the religious feasts they sponsored, the “gilde” of pagan Norse tradition.1 Possibly from the Norse invasions during the sixth through eleventh centuries, guilds found their way into Anglo-Saxon English, Norman French, and Germanic Dutch society.

As settlements oriented around commerce and production evolved in medieval Europe, their guilds became increasingly influential and specialized according to their region and its economic niche. The ideologically focused guilds of Ravnica each owe some element of their inspiration to medieval guilds which flourished in different periods throughout Germany, England, France, and Italy.

Military Guilds: Boros and Azorius

Throughout the eleventh and twelfth centuries, guilds dedicated to the maintenance of communal peace appeared throughout English and French townships. The extent of their authority, however, extended beyond the punishment of thieves and criminals. In 1070, the citizens of the town of Mans formed a guild or commune against the depredations of a neighboring lord, Godfrey of Mayenne, and had their rights and grievances recognized by the King. The citizens of Cambrai organized against their own landlord, the Bishop of the region, and shut him out of his own city when he came to re-assert control.2

The white-red Boros and white-blue Azorius, despite their chaotic-versus-lawful approaches, share with these guilds of public defense a focus upon order and protection and the military power to back it up. The strongest manifestation of military guilds appeared in high medieval northern Italy, where militia communes were formed in Sienna, Florence, Venice, Milan, and elsewhere to protect against the patchwork of petty rivals that inhabited the Italian peninsula as well as ambitious princes of the Germanic Holy Roman Empire to the north.

One of the most successful, the Lombard League, was organized in 1167 CE to counter Imperial annexation by the Emperor Frederick I Hohenstaufen. Militias drawn from the cities of northern Italy marched under the aegis of the Lombard League for nearly a century, until the final defeat and destruction of the Hohenstaufen line in 1250 CE. The semi-professional soldiery of this commune share with the Azorious arresters and Boros legion an organization that drew upon citizen-soldiers and mass mobilization rather than a noble military class – a precursor to the modern military.

Religious Guilds: The Selesnya and Orzhov

Although the power of the land-owning noble class was greatly diminished in the medieval city, the Church and its rituals still dominated social and public life and were of great importance to urban guilds. In fact, the original Danish “gilds” owed their creation to the celebration of religious holidays with public gatherings. These same functions continued to be met by Christian guilds after their introduction to the European mainland.

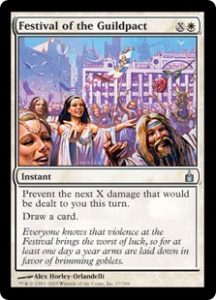

The primary functions of many of these religious guilds, which included both lay persons and religious authorities, was to mark and celebrate holidays in appropriate fashion. These “Calender Guilds” organized charities year-round, processions for major holidays, and the dramatic “passion plays” which marked the sacrifice of Christ at Eastertide. As with both the Selesnya and Orzhov, however, there was more than a hint of social control in the celebrations sponsored (or shunned) by the religious guilds. Drinking, swearing, dicing, and dancing were each banned at various points by Christian guilds throughout European cities in an effort to curb “heathenish” behavior which persisted during celebration of holy days – ignoring, of course, the pagan roots of the guild organization itself.3

Trade Guilds: The Izzet and Simic

But by far, the organizations with the greatest and most lasting influence over medieval urban society were the craft and mercantile guilds. The Izzet and Simic, with their innovations and additions to the public works of Ravnica, share with the historic trade guilds of Europe an innocuous source of influence. Without military guilds, the city might go unprotected; without religious guilds, the city would lose a centerpost of learning, guidance, and public life. Without the basic services, economic production, and trade provided by mercantile guilds, however, the city would simply cease to exist. Craft and commerce kept the city fed, paid for its defense, and built its walls and churches, and the guilds which controlled these central forces wielded huge regional power.

The Hanseatic League provides an example of the reach of a humble merchant guild. First organized as a network of trader communes (called “hansa” in northern Germany) from the tenth-thirteenth century CE, the Hanseatic League grew to include members from the region of the modern Netherlands to Russia. By trading in wools, amber, and salted comestibles, the merchants of the individual hansas each achieved independence from local lordship, answering instead only to the authority of monarchs or the Holy Roman Emperor. During the thirteenth century, it held a complete monopoly on trade in the North Sea, carrying goods from Constantinople and Baghdad as far as London and Novgorod. At the height of its power, the Hanseatic League conquered Denmark in 1370 CE, forcing it to cede exclusive trading rights to the guild.

Trademarks like the Simic’s here and modern copyright each owe their roots to guild protections in the medieval period.

The Izzet and Simic each are undeniably more magical than the Hanseatic League, and are overall less concerned with trade and commerce as their source of power. Despite their draconic overlords and merfolk mutants, however, they are rooted in the fabric of medieval urban life, providing public works for Ravnica’s citizens, offering trademarks on goods, and ultimately contributing to the health and wealth of the city. Without them and their mercantile counterparts in medieval Europe, the pre-modern city could hardly survive, dependent as it was upon trade, transport, and public safety to stay fed. Magic’s plane of Ravnica is such a unique and enjoyable setting because it is rooted in some of the most fascinating history of the medieval past – the development of guilds and the growing power of traders, merchants, and craftspeople through the feudal era and into the modern day.

1Frederick Armitage, The Old Guilds of England (Weare & Co., 1918), 8-9.

2Toulmin Smith, Esq., English Guilds (Truber and Co., 1892), lxxxviii.

3Smith, lxxxviii. This book had a very long, very informative introduction.