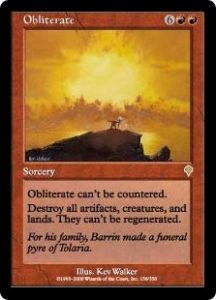

This week’s Uncharted Realms takes us back to the plane Zendikar, sometime before the events of the original Zendikar block but after the imprisonment of the Eldrazi by the planeswalkers Nahiri, Sorin, and Ugin. Nahiri, having settled into the emotional distance and moral relativity of the old planeswalkers’ immortality (a neat reminder of the pre-Mending era), is awakened to the threat of the Eldrazi stirring from their arrested motion. She tracks the would-be jailbreak to its source, a vampiric cult operating up in the Akoum mountain range, and obliterates them, healing their sabotage of the hedron network.

Although Zendikar is a world unique to the Multiverse of Magic, the themes that animate its plot are not. The Eldrazi, mistaken as gods by Zendikar’s inhabitants, tap into one of the strongest elements of human belief, hope, and fear: the end of days.

It’s the End of the World as We Know It

What do the 16th century English Puritans, the 1st century Bar Kokhba revolutionaries, and the vampires from this week’s Uncharted Realms all have in common?

They all share a common belief in the near arrival of divine forces accompanied by the end of the world.

Religious eschatology (beliefs regarding the end of the world) is prevalent throughout the medieval and pre-modern history of the Abrahamic faiths of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, influencing major events in the lives and politics of the faithful.1 The Puritans, English religious separatists from the Anglican faith in the 16th century CE, believed the church of England to be so hopelessly corrupt as to signal the downfall of man and the imminence of Judgment Day, and so sought to recreate a nominally pure Christian commonwealth across the Atlantic Ocean in preparation for divine reckoning. The Israeli leader Simon Bar Kokhba was hailed by his followers as the Messiah of Jewish belief in the 1st century CE, sparking a successful revolt against oppressive Roman rule. And belief in the Day of Judgment is counted among the six core articles of faith in Islam, influencing the history of Sufism and the development of the Baha’i faith.

It is natural that both human belief on Earth and religious cults on Zendikar would concern themselves with the end of the world, not least because the gods of Nahiri’s home plane are, in fact, sealed-up tentacle monsters with reality-obliterating power. In fact, many of the religious groups in Earth’s history that focused upon their faith’s version of the end of days did so not out of a sense of pure fear, but instead with a perspective of hope.

…And I Feel Fine

In Christian, Jewish, and Islamic medieval eschatology, the end of the world was understood a destructive event, accompanied by the clash of nations, the rise of tyrannical or faithless rulers, and even in some versions the appearance of a supreme evil. All of these occurrences, however, were a prelude to the final chapter of the world: the return or arrival of divine authority to sweep away all temporal nations and rivalries, and judge the souls of the living and the dead.

For many people of the pre-modern (and modern) era, who faced death and hardship in their everyday life from malnutrition, disease, and human violence, the concept of the apocalypse culminating in Judgment Day was a prospect to be celebrated as much as feared. The Puritans, bar Kokhban Israelites, and countless others in Abrahamic tradition saw the imminent end of days as a transcendent event, surpassing the miseries and heartaches of everyday life to wipe away earthly suffering and tyranny in divine rapture. The violence which served as the direct accompaniment to divine irruption would be the last terrible calamity to befall the world.

The concept of the Apocalypse culminating in Judgment Day was a prospect to be celebrated as much as feared.

“When the Day of Judgment shall arrive upon us, then our God shall come,” wrote the Puritan magistrate Cotton Mather in the account Magnalia Christi Americana, “And a Fire shall devour all before him… The Redemption of the Church, for which the Lord hath long been cried unto, will then be accomplished, but at what [cost]?”2 In these stark beliefs, borne of a daily reality that included hardship, heartache, and strife, one can see a reflection of the misguided faith in the Eldrazi that persists on Zendikar.

The cultists who sabotaged the hedron web in this week’s Uncharted Realms certainly don’t get much of a chance to explain themselves, as Nahiri buries them in stone before they get to preaching. But their actions are congruent with a great deal of religious history on Earth. Their unintentional role in the destruction of their plane would agree with the apocalyptic beliefs of many peoples, who saw in the end of days an event to be celebrated as much as feared. In the end, perhaps they acted in accordance with the wishes of their god, as Mather exhorted: “If the Hour were now turned, wherein the Judge of the whole World were going to break upon us with fierce Thunders, and make the Mountains smoke by his coming down upon them… could you gladly say, ‘lo, this is the God of my Salvation, and I have waited for him?’” In His wrath and calamitous arrival, who could tell the Judge of Mather’s sermon from the Eldrazi of Zendikar’s destruction? And who could resist His command?

Curtis Wiemann writes about that old-time religion and loses at Magic.

1 And in many other faiths as well, including pre-Columbian Central American religion as well as Buddhism and Hinduism throughout the world today.

2 The Magnalia is a collection of sermons and histories compiled by Mather in the first generations of American Puritan settlement in New England. Its full contents can be found here.